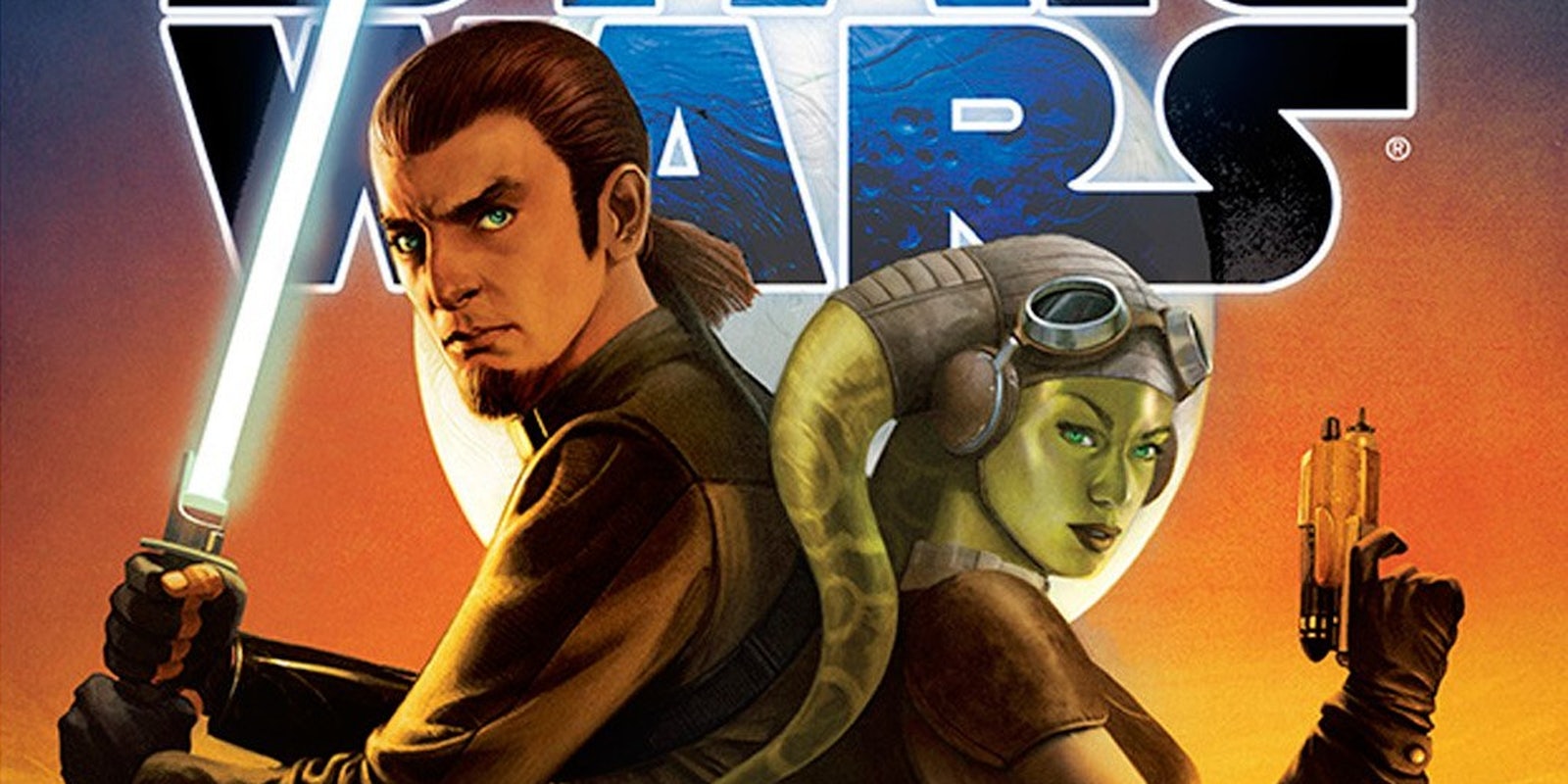

Today, Random House is releasing the first canon Star Wars novel, Star Wars: A New Dawn by John Jackson Miller, which takes place shortly before Disney’s upcoming television series Star Wars Rebels. The book explores the early days of the Empire in a system rich with resources and tells the story of the first meeting between two of Rebels’ main characters, Hera Syndulla and Kanan Jarrus.

Miller, a fan-favorite Star Wars author, rose to prominence in the Star Wars community writing comics like Knights of the Old Republic and Knight Errant and short stories like Lost Tribe of the Sith before authoring several novels set in the galaxy far, far away. Prior to A New Dawn, his latest Star Wars novel was Kenobi, which sees the eponymous character struggling to settle in on Tatooine in the middle of his self-imposed exile there. Kenobi was widely praised by reviewers and fans alike when it was released last August, so Miller was a natural choice to write the first book in Disney’s new era of Star Wars publishing.

A New Dawn lives up to its title both literally and symbolically. In a literal sense, it marks the start of a new era for Star Wars publishing, as it kicks off the novels of Star Wars’ new unified canon. Symbolically, it also represents a shift in storytelling at Lucasfilm, toward a continuity in which the interplay between different media like television and books is more symbiotic than it had been in the past. The creators of Star Wars Rebels—which premieres this fall—have said repeatedly that Disney is encouraging Lucasfilm to use all available media to create a rich universe. As its title implies, A New Dawn is only the beginning of that effort.

Today, as a new era begins for Star Wars storytelling, we speak to Miller about the history, themes, and messages in his latest novel.

How did you get the opportunity to write this book?

In the fall of 2013, I spoke with Random House about doing a book that would serve as a prequel to the Rebels TV series, for release before that series debuted. The notion was that a number of the other books that were going to be on the calendar were going to be darker in nature—and of course we see that with Tarkin and Lords of the Sith—and so they were looking for a more heroic take, a more traditional space-opera story. Once I got some information from the Lucasfilm Story Group about what Rebels was going to be about, and once they suggested a possible part of the timeline that would be open for me to suggest something for, that’s when I proposed doing something that would tell the story of the first meeting of Kanan and Hera, two of the revolutionaries from Rebels, and have it set in a part of the Empire where its massive industrialization program is aggressively ramping up.

I thought that this would be a good chance to show people what life under the Empire in this point in time was like, and at the same time tell a story that would set the table for Rebels.

What was your first impression of Rebels when you started seeing material from it?

I got the story bible and the details for the first season, so I knew who the other characters were and what the general themes of the first season would be. It’s all very well thought-out, because by that point … Earlier in October I had seen the panel at New York Comic-Con where they already had some artwork there. Things were progressing. As time went along, as I was working with the Story Group, I did get some additional information about what was happening. It’s a very impressive series, very impressive how much work goes into these things.

When you were working with the Lucasfilm Story Group, how minutely did they help guide your work? How often would they say something like “We need you to characterize this thing in your book differently because it’ll be relevant in this other project”?

Most of the guidance that I got from the producers came in the earlier stages where I was working on the plot and on what Kanan and Hera’s relationship would be like and what their feelings about the galaxy, about the Empire, would be like at that point in time. I already had a fairly good idea of what technology would be like at that point, where Imperial progress toward where they would be in A New Hope … would be by the time of my book.

[For] most of the really nitty-gritty details of the galaxy in this timeframe, I seem to have been in sync with what they wanted.

You studied the Soviet Union extensively and were on your way to a doctorate in Soviet studies when the regime collapsed. How did your knowledge of the U.S.S.R. influence your portrayal of the Empire in this book?

The Soviet Union turned a country that was an agrarian society––and also several satellite nations that it conquered––into an industrial-military powerhouse over the course of a couple of decades. This was no small feat. It ended up costing more lives than were lost in World War II. Over 20 million died during the collectivization period where they [were] moving everybody to the collective farms and taking control of industry and ramping up production everywhere.

It struck me that, whatever happened in the galaxy far, far away would at least have a somewhat similar dynamic. This is less than a 20-year period in between Episode III and Episode IV. While the Republic is certainly an advanced society with heavy industries, it was not turned entirely toward the production of arms, toward the production of Star Destroyers, toward the production of Death Stars. That takes change to a society, and that is one of the things that A New Dawn tries to depict by showing life on one of these resource planets: How things have changed really quickly because of Imperial meddling and them taking the place over.

One of the big themes in the book is surveillance. Zaluna makes a lot of familiar-sounding observations about mass government surveillance of citizens in the name of security. Was your goal here to draw parallels to our own world?

It was never a case where I wanted to rip something from today’s headlines, even though we had the whole Edward Snowden thing that happened in 2013. It was unavoidable that, in trying to detail how the Empire took control of society, we would get into their ability to watch the people and regulate what they were thinking and saying. That had to be part of it, but it struck me that it would be something where it would not have … [begun] overnight.

In fact, just as in our real world, surveillance of various kinds has gone on for decades, for centuries…any country that you want to name has done something to keep watch over somebody at some point in time. It struck me that a lot of the things that the Empire would be using would be things that started under the Republic, perhaps under a different heading. What was going on in the Republic? The Clone Wars: a war for the survival of the Republic against the Separatists. We can imagine a number of institutions that the Emperor would use later on being established in the Republic period by the Emperor [while he was Chancellor].

Of course, Zaluna lets us know that this [surveillance apparatus] even predates the Emperor, a lot of these things, because the company she works for is a company. Commercial surveillance is a big business. Commercial tracking of people is a big business; we know that very well now. The tools are already out there for the Empire to be able to draw upon and use. It’s just the case that in this book, we get a sense of how much they’re able to do and are doing.

Is it your sense that [Star Wars Rebels executive producer] Dave Filoni and his team are following a similar playbook of using “holdover” technologies and systems from the Republic in the new Imperial government?

I really can’t speak to anything having to do with Rebels, in terms of what they’re going to do.

One of the things fans are curious to learn from the new canon is how certain characterizations are maintained or changed. For example, the Empire’s treatment of aliens. There’s a scene where an Imperial officer pushes past one of the main characters, who is a Sullustan, and says, “Out of my way, creature!” In your mind, is the Empire as xenophobic as the Expanded Universe made it seem?

That was definitely an intentional wording on my part. We know from the films what the Empire looks like. We know from the films what society is like. We know that there does not seem to be any race-based or gender-based discrimination within humanity, but we’re not seeing all these stormtrooper outfits designed for different species like we saw for the Mandalorians years earlier.

This is just my impression here that there would be Imperial officers that would bear resentments that they wouldn’t feel any problem talking about like that character does. Does that manifest in [another book, comic, TV show, etc.]? I don’t…The book is the book, and the book doesn’t try to tip off what something else would be later on, because I don’t know how it will be handled in the rest [of the canon]. This book went through the Story Group and that particular depiction went through.

How is the Hera of A New Dawn different from the Hera that we’ll meet at the very beginning of Rebels? How did Dave Filoni help you with that specific aspect of the book?

That was probably the greatest area of input, on those two characters Hera and Kanan and how they would interact at this time, what they would think of each other, what they would think of the galaxy, what they would think of their own jobs, in terms of what they should be doing. Hera, [is] this calm, moral center of the book, this figure who tries to be understanding but doesn’t have a lot of time for people who are going to waste her time––and of course she certainly thinks Kanan is likely to waste her time here at the beginning of this book. She’s not hurtful about it, she’s kind about it. She has her patience tested and manages to come out of this book as a character that we like, as a character that we think will be really well-suited to knitting together a movement of a lot of different sorts of people.

And what about Kanan? What guidance did you get for how he should be portrayed here? Did you look to the Han/Leia dynamic in A New Hope for characterization guidance?

Obviously the Han/Leia relationship is the prototype Star Wars relationship. Certainly, Hera and Princess Leia have sort of the same driving goals that they’re working toward. Hera is perhaps a little more patient than Princess Leia is with people that don’t fit the template.

Then, with Kanan, he doesn’t even have Han Solo’s delusions of wealth or grandeur or anything like that; he knows that wherever he goes in life, he’s still a marked man and he’s got to keep on going. Yes, they are similar to a degree, but with Kanan, his major overriding factor is that he’s hunted, or he feels he’s hunted, he feels he has to keep moving on. He just can’t let himself get too comfortable.

Up until the point where this book begins, [that feeling] has prevented him from having any sort of permanence in his life. Han Solo has permanence in his life in the form of the Millennium Falcon, in the form of Chewbacca. Kanan doesn’t even have that.

I thought Skelly was one of the most interesting characters in the book. He’s infuriating, but he’s also sympathetic. Can you talk about developing him and the role you wanted him to play in the story?

Skelly was there in every draft from the very beginning. Of the heroes, he’s probably my favorite character in the book, just because he is so damaged. He is what I imagine would exist: He is a Clone Wars veteran who is not a clone, he’s somebody who got dragged into that conflict, a conflict which anybody who is sort of tuned in would begin to question not long after it’s over. Because what was that really all about?

That all rolls up with this persecution complex and paranoia that he’s developed over the years anyway. You wrap it all up with detonation cord and there you’ve got Skelly. He is somebody who is a hero in his own mind, but it is really hard for anybody else to see that. Getting him to where he is at the end…if you can feel sympathy for him, that is a victory for the characterization, I think. That is what I was going for, but if you root for him, it’s in spite of yourself, because you know that this is a guy whose tactics are not necessarily what you want to see.

I thought that’s what was so great about him. You don’t really see this kind of complicated protagonist in many other Star Wars books. It’s either Princess Leia, who is a paragon of virtue, or it’s Han Solo, who can be frustrating but isn’t as much of a nuisance. Skelly seems like he must have been a challenge for you.

The basic notion at the beginning of this book was that the people who you get in revolutions at the very beginning are not the people who ought to be running them. Hera is this wonderful mastermind, but she is the exception. She’s not recruiting at the beginning, and part of the reason…is that she knows [that] the people who she’s likely to find at this stage of the game include a lot of people who might be unhinged. [laughs] Every revolution at it beginning attracts people who––either for the reason that they’ve been damaged by the system the way that Skelly has been, or just because they have problems in socialization––are outcasts, not insiders, in society.

Part of the whole initial thinking with this book was that I was going to show some people who were least likely to succeed in revolution-building being brought together by Hera and being made to be useful by Kanan. She’s the strategist, he’s the tactician.

Why make Vidian an efficiency expert? Did you want to explore the logistics of the Imperial transition, or was it something else?

That’s absolutely it. We are, as we said earlier, transforming this trading organization (the Republic) into this military machine in a short period of time. How does it get there?

I tussled with this issue once before when I was writing Knights of the Old Republic and dealing with the Mandalorian Wars. Because, at least as they were described in the very beginning, over the course of three or four years the Mandalorians went from one planet to having troops heading for the capital. The actual footprint of the Mandalorians was later reduced, or at least confined to a specific area, when [The Essential Atlas] came out, after I consulted with Jason Fry and Dan Wallace. But if they really had wanted to try to conquer most of the galaxy in three years, that would have required huge, huge logistical measures, which I thought for a group of nomads would be complicated –– not out of the question, because Alexander the Great conquered a lot of space in a short period of time too. He had a system for bringing the people that were conquered into the army and assimilating new cultures.

In those [Knights of the Old Republic] comics, I got to it by the idea of the War Forges that [the Mandalorians] were developing. They actually adopted some uniformity; the Mandalorians never really liked uniforms, but we had the Neo-Crusaders from the video game already, so we figured, “OK, let’s bring those in and make them part of it,” so that there would be a way to process all of these planets that were being conquered and bring in new peoples.

In the case of the Empire, the challenge was, we’re going to end up with hundreds and thousands of Star Destroyers before too long. The Emperor has to be able to feel completely confident by the end of 18 [or] 19 years here that he can project power wherever he needs to send it even without the Death Star being ready. He’s got to be able to exercise his power when he needs to at a moment’s notice. It struck me that there had to be some kind of process for transforming what had been commercial industries operating purely for profit into something where those industries were working toward what the Emperor wanted, producing the things that the Emperor wanted. It’s not a case where he’s running around taking over companies or things like that; the Emperor uses a very mixed bag of tricks to get everybody working toward the same goal for him, and Vidian is one of his tricks.

Count Vidian is somebody who, under the Republic, was a turnaround expert, one of those guys that fixes industries that are in disrepair or corporations that are failing. We can see that he clearly was somebody that supported Palpatine on the rise during the Republic’s time, and Palpatine has rewarded him with a position of doing his bidding here, helping to grease the wheels for the Imperial machine now that the Empire is in charge.

You develop an interesting dynamic between Count Vidian, Baron Danthe, and Captain Sloane. How much of that came out of your research on the Soviet Union and its bureaucracy?

Well, I shouldn’t make this all about the Soviets. The actual degree [I have] is Comparative Politics; even though the focus is on Russia, I did look at other totalitarian states and how they rose.

There are always institutions that existed before, unless you completely wipe them out, that end up evolving in the new order. This was a case where the Imperial Navy began as the Republic Navy. The Imperial Navy would have had its first graduating classes coming out of the Academy during the Imperial era in this timeframe where Captain Sloane is getting her first posting. It struck me that she would be representative of the new Imperials, the new people [who] were actually energized by the early days of the Empire, the feeling that, “Alright, we’re no longer going to just be fighting these Separatists to keep the Republic together. We’re going to actually be going out and planning to build and build and build, and grow and grow and grow.”

The book gets a little bit into some of the forces that were keeping the Republic from growing any faster than it was for many years. The Imperials look at [those constraints] and see an opportunity. Yes, she is certainly happy to try to balance the interests of her organization, the Navy, with the influence that she has to follow that comes from the Imperial administrators, of whom Vidian is one. But we also have this aristocracy that has continued to exist from the Republic days, so there are still some voices there [like Baron Danthe] that she’s got to listen to.

One of my favorite lines in this book is Obi-Wan’s comment that, when it comes to the history of the Jedi Order, “There are truths, and there are legends touched with truth, and all can teach you something.” Am I right in guessing that you included this line in part to break the fourth wall and make a statement about the EU?

If it says something to you… [laughs]

What I would say to that is… let me see how to put this… I think Obi-Wan speaks the truth. We are looking at a lot of new material coming in from these new movies. We’re looking at a lot of new things that are going to be done, and there are going to be opportunities to pull things from the past, to take inspiration from the past, and tell stories that draw on some of these things.

[It’s] the same way that…how long have we been making Robin Hood movies? How long have we been making stories about King Arthur? These are all characters who have some historical roots to them, but we don’t entirely know who they were or everything about them. That doesn’t stop us from drawing upon those memories.

It struck me that the situation that the students of the Jedi would be dealing with, in trying to understand their own histories, would be similar. There would be, for them, things out there that they would know something about, or a lot about. But certainly, every story from the past would still be important, because they would all teach something.

If the reader wants to take some out-of-universe relevance from that, I’m fine with the message.

The main characters in your major Star Wars books and comics—Zayne Carrick, Kerra Holt, Ben Kenobi, and now Kanan Jarrus—are all adrift and looking for guidance and direction. How did you get “typecast,” so to speak, writing this kind of character? Was it always your preference, or did you just try it and end up enjoying it?

The hero that I met first in Star Wars was Luke Skywalker, and Luke Skywalker did not begin his career with a purpose. [He] did not begin his career with a person telling him where to go, what to do, what his life would be like. He did not think he had a destiny.

Zayne Carrick [from Knights of the Old Republic] did not think he had a destiny. He knew for sure he didn’t have the destiny that his master saw for him. Kerra Holt [from Knight Errant] didn’t think she had a future beyond her first mission. She thought that she was out there [in Sith space] to fight the good fight and die. She didn’t realize that there was a bigger role for her as the savior of individuals out there.

Certainly, of course, with Kenobi [in the novel of the same name], he is cut off as no Jedi [up] to that point had been cut off. Even Qui-Gon isn’t answering the phone. So he’s got to make his decisions on his own.

Kanan is in a similar boat. I think the way to really bring the galaxy home––when we’re talking about a realm that is so big, so huge––is to focus in on one person whose concerns are much more local, and then slowly open the world up to them and invite them to take their first step into a larger world.

What upcoming projects do you have beyond the galaxy far, far away?

Yeah. I have, releasing on Jan. 27, Star Trek: The Next Generation: Takedown. This book is a lot of fun. It is a perfect jumping-on book for somebody who hasn’t read Trek to date and is just familiar with the TV series. This is a story that pits master against student, Captain Picard against newly-minted Admiral Riker. [There are] two different starships––Enterprise and Riker’s vessel. Riker’s vessel happens to be much, much faster. [It has] the two of them on opposite sides of a particular conflict.

It is a really fun space chase novel. It allows me to tell a kind of naval adventure that I have really wanted to do and which I think Star Trek lends itself really well to. This is a rare story where no character sets foot on a planet even once. This is really a race in space. I had so much fun writing it.

I’m not fleeing to the mirror universe. [laughs] I’m not leaving the galaxy far, far away. But it is the case that certain kinds of stories are more suitable for Star Wars and some are more suitable for Star Trek. Some of them are more suitable for other milieus, or even things like my own Overdraft universe that I came up with. Different sorts of stories will speak to different audiences.

Since you said you’re not fleeing the galaxy far, far away, I have to ask: Are you working on anything for Star Wars?

If I could tell you, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. [laughs] If I were, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. The future is always in motion. That’s what we say. That’s the good line there.

Image via Lucasfilm