Warning: The story contains minor spoilers for Quantum Break.

If you thought before that video games try too hard to be like film and television, Quantum Break has given you a whole new way to consider the issue.

Remedy Entertainment calls Quantum Break a revolutionary experience, but it’s really another interpretation of transmedia storytelling—telling a unified story across multiple forms of media. Defiance, for example, was released in 2013 as a television show on the Syfy channel and as an MMO shooter game on PC, PlayStation 3, and Xbox 360 the same year.

Quantum Break plays with the idea of transmedia storytelling by throwing all the media together under the same roof. You don’t have to access part of the story on a game console, and head to a television or comic books for the rest of the narrative. Quantum Break is both a traditional video game and an episodic television series accessed through the same package.

The practice of using live-action footage directly within a video game goes back to the early 1990s. Where Quantum Break differentiates itself is by using it not merely for short narrative linkages between levels, but presenting it in full-on episodic format.

The first four Acts of Quantum Break the game should take you between 90 and 120 minutes to complete, depending on difficulty and whether you’re a completist. Each of the first four Acts is then followed by an episode of Quantum Break the television show, which runs about 25 minutes. The way Quantum Break weaves live-action video into the story is by far the most interesting part of the experience.

It makes me wonder how the total product would change if all the same scenes were produced in-engine, like traditional video game cutscenes. Would Quantum Break lose anything in the process, other than the novelty marketing angle? And if the answer is “No,” doesn’t that make the use of live-action video just a gimmick?

Quantum Break is about Paul Serene, played by Aidan Gillen from Game of Thrones, and his best friend Jack Joyce, played by Shawn Ashmore from the X-Men movies. Serene is the manager of a research project at Riverfront University, where the scientists believe they have devised a way to manipulate time. Serene is impatient to prove that the project has been a success, so he calls Joyce to help him conduct an unauthorized experiment.

The resulting accident creates a fracture in the fabric of time that will inevitably grow larger, spreading havoc across the face of the planet until time itself collapses and stops completely. The accident also results in Serene and Joyce gaining super powers that allow them to manipulate time.

Serene has a plan to repair the fracture, but it leaves most of humanity out in the cold. It’s up to Joyce to save the rest of us. I can’t tell you any more about the story because this is time-travel fiction, and time-travel stories are all about loops and paradoxes and reveals, and then watching the story a second time and recognizing all the foreshadowing for what it is.

I’m a sucker for time travel but even with that bias acknowledged I think Quantum Break does tell an entertaining science-fiction story. I didn’t anticipate all the time paradoxes. I did honestly care when characters died. There were plot elements held in reserve for a possible sequel that I really wish Quantum Break had investigated, but those elements still contributed to some interesting world-building that I enjoyed.

I enjoyed Quantum Break in the same way I enjoy Marvel superhero movies. They’re fun to watch while I kick back and eat some popcorn. But when I go to see The Avengers I don’t have a control pad in my hands, and there’s where Quantum Break gets confusing for me. Sussing out the relative importance of the two halves of Quantum Break messed with my head as much as trying to sort through all the story’s causality loops.

The game half of Quantum Break follows Joyce as he tries to take control of technology owned by the Monarch Solutions corporation, and to use that technology to repair the expanding fracture in time.

Monarch bankrolled the time control experiment at Riverfront University. The corporation also owns large portions of the city of Riverfront, and has a research lab on a nearby island. Joyce therefore spends much of his time trying to slip past Monarch’s security forces as they turn the area upside down looking for him.

Remedy Entertainment also developed the first two Max Payne third-person shooter games. In Max Payne the player uses a bullet-time ability (think Matrix-style time slowdowns) to pull off complex acrobatics and survive gun battles against overwhelming odds. When Monarch finally catches up with Joyce, the fight scenes in Quantum Break play out similarly to how the fight scenes worked in Max Payne, only now you can do so much more than simply slow time down.

Among Joyce’s powers are the ability to temporarily freeze small pockets of time, dash forward in quick bursts of speed and slow time down temporarily to line up the perfect shot, and distort local time around him so radically that it knocks enemies back like a punch to the chest.

Joyce’s abilities all have associated cool-down periods. Enemies won’t allow Joyce to remain in cover for very long, and he can’t take a lot of punishment, so the fight scenes are about managing Joyce’s time control powers properly and stringing together effective combinations of abilities.

I played Quantum Break on normal difficulty for expediency’s sake. I suggest that you crank up the difficulty. The more measured and precise you have to be with Joyce’s time powers, the more satisfying the fights become. I didn’t even have to pay attention to whether or not I upgraded Joyce’s powers the further I got into the game, and that’s what got me wondering about how important all the fighting was in the first place.

Again, I could have made the combat more challenging, but what mattered to me more than having a satisfying combat experience was getting through to the next part of the story. There isn’t much variety in the enemy types, and I can’t imagine that the successful tactics would be any less formulaic even if the difficulty were cranked up.

As the fracture in time gets worse “stutters” begin to appear more frequently and grow much larger in size throughout Riverport. Everything inside of a stutter is either frozen in time, or shifts back and forth between different parts of the local timeline. That means a car crash can happen right in front of Joyce, unhappen, and then happen over and over again.

Sometimes Joyce has to find a way through that car crash, which means freezing time at just the right moment and running through a gap before time starts again. Joyce might be caught in the middle of a disaster that’s frozen in time, and he has to find a way through the wreckage. Or it might be as simple as manipulating a single object within time, like raising a fallen catwalk to where it was before it had fallen, so Joyce can run across it.

I wouldn’t call these “puzzles” by any stretch of the imagination. They usually felt like busy work, just a series of ways for Remedy to drive home the point that Joyce can control time. Deaths often felt very cheap—whether or not I died came down to how touchy the game was about where I placed a time bubble or precisely when I made a speed dash to try and close a gap.

And the save points on these events too often took place right before Joyce delivered a line of dialogue. I would die, hear Joyce say something, almost immediately die again, reload, hear Joyce say something, and die again in my own personal version of time-travel hell.

The television show half of Quantum Break is less about Jack Joyce and the supporting characters that are helping him, and more about Paul Serene, his right-hand man Martin Hatch, played by Lance Reddick from The Wire and Fringe, and a series of secondary characters employed by Monarch Solutions.

Each episode begins with a short in-engine sequence in which you control Paul Serene and have to make a decision. You can preview either choice to see what the consequences may be, and then your choice decides what footage you’ll see when the episode of the show kicks off moments later.

I was unimpressed with the choices because they almost always had a “correct” answer, in terms of keeping with the characters as I understood them and how the story was progressing. It felt as if a screenwriter had provided me with two alternate edits, one that made sense and the other that the screenwriter threw in there just to see what I’d do with it, rather than two choices that felt equally valid.

You are allowed to skip the television episodes if you want to, and if you did, you might only miss out on some of the subtleties during the game half of Quantum Break. You could probably look at the show episodes as all the material you get when you read the novelization of a movie, versus just seeing it.

The production values on the Quantum Break episodes aren’t quite where I’d hoped they would be. The episodes use a lot of found locations that aren’t dressed particularly well. There’s a reveal in the last episode that should have been a “wow” moment, but instead I kept looking around at all the concrete floors and walls with objects thrown over them in an attempt to hide that the scene was shot in what looks like a building in the early stages of construction.

The Monarch Solutions uniforms aren’t very good, and there are props that are just Monarch Solutions decals thrown over objects. The Quantum Break episodes feel like the Halo live-action stuff that Microsoft’s been doing for the last couple of years, but with a smaller production budget.

Microsoft did get its money’s worth out of performances from Gillen, Ashmore, Reddick, and Dominic Monaghan from The Lord of the Rings, who plays William Joyce, Jack’s brother.

All the acting, not just the performances from the recognizable players, is solid. I’m also a sucker for a fight scene, and enjoyed the stunt work in Quantum Break.

Production values aside, I enjoyed the television episodes in Quantum Break more than I had expected to. I had dismissed the idea of embedding a television show inside a video game as just a hokey marketing ploy, but I think I may actually go back to walk through different Junction Points, make different choices, and see how the episodes change.

But I’m still not sure why the live-action video is there in the first place.

It’s not as though all of that content couldn’t have been replaced with traditional, in-engine cutscenes. The motion capture in Quantum Break is excellent. It had to be if the game was going to switch between Ashmore and Gillen as video game characters and Ashmore and Gillen as live-action television stars without a glaring transition.

Quantum Break is an example of a high-concept pitch that pays off, and I really want to know who came up with this idea in the first place. Was there a creative intent beyond just trying to use incorporated live-action footage to a much larger scale than anyone ever has, just to see what the results looked like?

I’d like to think there’s more going on under the hood creatively in Quantum Break other than, “Let’s make something really cool.” The video game industry being what it is, we’re unlikely to get any sort of behind-the-scenes look at the early creative process that is divorced from a marketing campaign until a few decades from now.

Quantum Break left enough of an impression on me that if I’m still around in that distant future when a former developer from Remedy finally gives a detailed look at what the studio was thinking when it came up with the idea for Quantum Break, I’ll be listening with rapt attention.

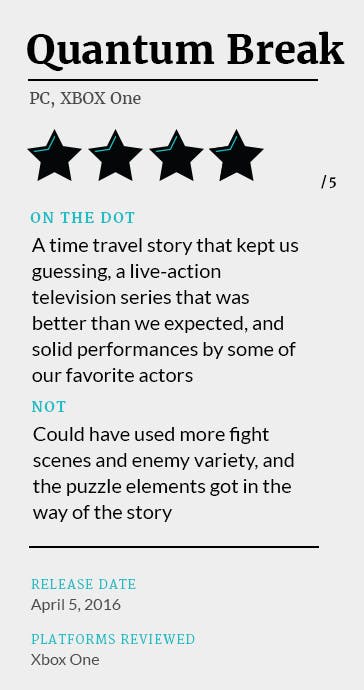

Score: 4/5

Screengrab via Microsoft

Disclosure: Our Xbox One review copy of Quantum Break was provided courtesy of Microsoft.