There was an outpouring of grief and anger over the weekend as news spread that Aaron Swartz, the 26-year-old hacker and technologist had committed suicide Jan. 11, just months before his trial on felony hacking charges was set to begin.

Now tens of thousands of his supporters are taking to the official White House website to hit back at the district attorney who they claim “hounded” Swartz to his death—and to seek a posthumous pardon from President Barack Obama.

A computer prodigy and high-minded crusader for the freedom of information, Swartz coauthored the RSS 1.0 standard, a tool for easily subscribing to blog posts and other data streams online, and helped forge the Creative Commons licensing system, a copyright standard that enables the easy spread of content across the Web. His nonprofit activist group Demand Progress played a key role in stopping the draconian Stop Online Piracy Act last year.

In July 2011, Swartz was indicted on federal charges for allegedly hacking into JSTOR, a digital repository of scientific and academic journals only available to paying subscribers, and downloaded nearly its entire archive over a three-month period.

The indictment claimed that Swartz planned to distribute those articles online via file-sharing networks. He never did. Instead, Swartz said he returned all 4.8 million articles and settled all civil claims with JSTOR independently—a month before the federal indictment was filed.

Explaining her office’s decision to pursue charges against Swartz anyway, Massachusetts District Attorney Carmen Ortiz reportedly said “stealing is stealing, whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars.”

Earlier today, the Wall Street Journal reported that, just two days before Swartz committed suicide, negotiations for a plea deal with prosecutors had collapsed.

If found guilty on all 13 charges, Swartz would have faced 35 years in jail.

But did he commit a crime in the first place?

“I know a criminal hack when I see it. and Aaron’s downloading of journal articles from an unlocked closet is not an offense worth 35 years in jail,” Alex Stamos, the defense’s expert witness on the case, wrote on his blog Saturday.

MIT allows guests on its network to access JSTOR files, and JSTOR allowed anyone on that network to download an unlimited number of files.

Stamos continued:

“If I had taken the stand as planned and had been asked by the prosecutor whether Aaron’s actions were ‘wrong’, I would probably have replied that what Aaron did would better be described as ‘inconsiderate’.”

In 2008, Swartz exploited a loophole to legally download millions of pages from PACER, essentially liberating 20 percent of the federal court system’s archive of public digital court documents, which normally sit behind a 10-cent-per-page paywall. The FBI investigated but did not press charges, but many have since speculated the government’s seemingly over-zealous pursuit of Swartz in the JSTOR case may have stemmed from lingering anger over his brazen PACER feat.

Swartz suffered from occasional bouts of severe depression, agonizingly chronicled on his blog and in a heartbreaking post Saturday by his friend Cory Doctorow, the BoingBoing editor and author. Suicide and depression stem from complex mental health issues. But those who knew Swartz best are nevertheless condemning the federal government’s decision to pursue its case against him.

In a statement Sunday, Swartz’s family declared that his death was “not simply a personal tragedy. It was the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach.”

Lawrence Lessig, the Creative Commons cocreator and Swartz’s friend and mentor, didn’t mince words in denouncing the government’s behavior in his blog post “Prosecutor as bully.” Swartz, Lessig wrote, was “driven to the edge by what a decent society would only call bullying.”

He continued: “I get wrong. But I also get proportionality. And if you don’t get both, you don’t deserve to have the power of the United States government behind you.”

For Dan Kennedy, a journalism professor at Northeastern University, Ortiz’s behavior in Swartz case is hardly surprising. Kennedy has followed her for years and sees striking parallels in her earlier, zealous prosecutions of a Boston-area pharmacist and a state senator.

“Ortiz’s vindictiveness toward Swartz may have seemed shocking given that even the victim of Swartz’s alleged offense — the academic publisher JSTOR — did not wish to press charges. But it was no surprise to those of us who have been observing Ortiz’s official conduct as the top federal prosecutor in Boston.”

Swartz’s name and Twitter handle, @aaronsw, were mentioned more than 200,000 times on the social network over the weekend, and his name likewise dominated the front page of influential technology news community and aggregator Hacker News over the same time period. Meanwhile, in a tribute to Swartz, academics are releasing their research papers to the public for free.

The groundswell of support and outrage swept onto the official White House website on Saturday in the form of two petitions that have received more than 15,000 signatures combined.

“Remove United States District Attorney Carmen Ortiz from office for overreach in the case of Aaron Swartz,” demanded one. More than 12,000 people have signed the petition, half of what it needs to receive an official response.

It is too late to do anything for Aaron Swartz, but the who used the powers granted to them by their office to hound him into a position where he was facing a ruinous trial, life in prison and the ignominy and shame of being a convicted felon; for an alleged crime that the supposed victims did not wish to prosecute.

A prosecutor who does not understand proportionality and who regularly uses the threat of unjust and overreaching charges to extort plea bargains from defendants regardless of their guilt is a danger to the life and liberty of anyone who might cross her path.

Another urges President Obama to posthumously pardon Swartz. It’s received 2,739 signatures.

“President Obama has the power to issue a posthumous pardon of Mr. Swartz (even though he was never tried or convicted). Doing so will send a strong message about the improportionality [sic] with which he was prosecuted.”

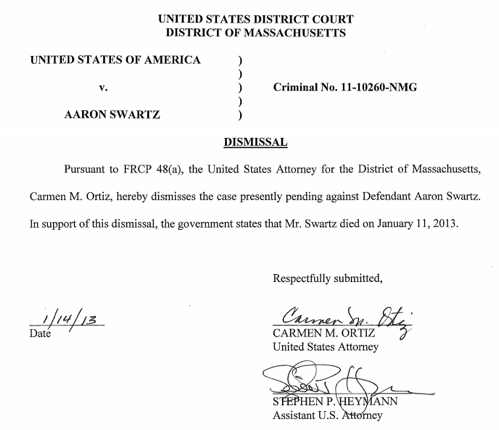

Ortiz’s office has declined to comment on Swartz’s suicide, citing the privacy of his family. Earlier today, the office dismissed charges against him, the Associated Press reported.

“The government states that Aaron Swartz died on Jan. 11, 2013,” the dismissal letter reads.

Photo by creativecommons/Flickr