In its effort to prevent people from becoming radicalized terrorists, the FBI is willing to get creative. Just don’t ask them to explain their process.

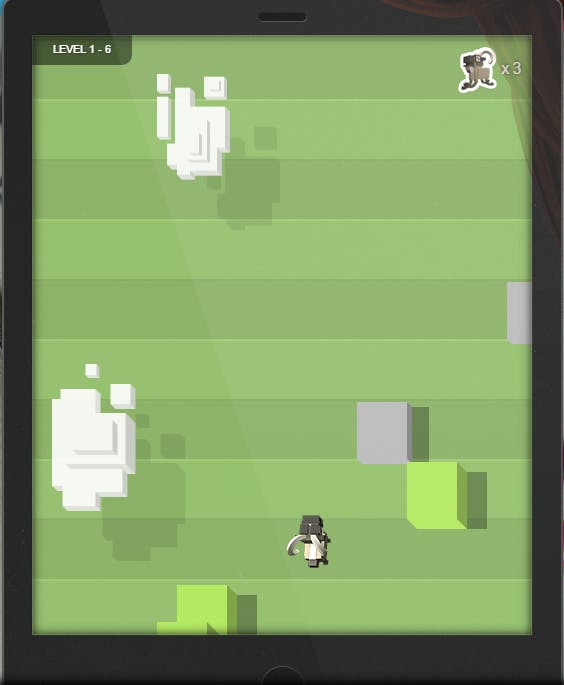

Earlier this year, the agency released a free, online video game where users play as a sheep, running through a field riddled with green blocks while white text showing pieces of “distorted logic” like “Our group is under attack” and “Our violent actions will result in a better future” scroll down the screen.

The game is called The Slippery Slope of Violent Extremism, and it is a real thing that exists. You can play it here.

Seriously, go play it. It’s an important cultural artifact about “the distorted logic of blame that can lead a person into violent extremism” as well as old-school, arcade-style action.

The game is part of a larger slate of online activities like quizzes about how to identify terrorist recruiters in online chat rooms. If you have decent reflexes, you can beat the entire game in about five minutes and become safe in the knowledge that you’re helping shepherd America into a terror-free future.

Yet, anyone playing the game can’t help but come away from the experience with a single, burning question: Why does this thing exist?

In April, the Daily Dot filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the FBI about the game. The request asked for “all documents—specifically memos, email correspondence, and budgets—around the development, release, and public reception of the FBI’s Slippery Slope game. It’s the one with the sheep.”

After about four months of back and forth with the agency, the Daily Dot finally received a concrete update about the status of our request. The search for records is currently ongoing, but the agency estimates it will be concluded in February 2018.

To recap: It’s going to take almost two full years to pull together the information on how a video game parable about a sheep ended up on the FBI’s website. According to activists who have spent years fighting for greater transparency at the FBI, this delay is the just par for the course.

Cannot process

In a lot of ways, J. Pat Brown was the inspiration for the Daily Dot’s attempt to use FOIA, a 1967 law that the public can use to obtain internal records. Brown works at MuckRock, a nonprofit that helps journalists, researchers, good government groups, and interested members of the public make FOIA requests of government agencies. In 2014, he stumbled onto something just as head-scratching as the FBI’s sheep game: the CryptoKids.

“You’ve got a system that is increasingly unequipped to do what it’s supposed to do.”

The CryptoKids is a project by the NSA aimed at getting kids and teens excited about computers, cryptography, and code-breaking through a group of cool animated teenage characters who work with the National Security Agency. “I realized [that a FOIA request] could give some accountability to this,” Brown told the Daily Dot in April. “It’s not just that I can’t believe money was spent on this. I could actually ask questions about why this money was spent, who did it, and who was responsible for it.”

To this day, Brown is still waiting to hear back about the CryptoKids, and he thinks the reason is likely similar to the FBI’s delay in turning over documents on Slippery Slope. “It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he said. “Because this request has not been pre-processed, and no one else has asked for it, paradoxically, it puts you in a situation where this kind of information is actually harder to get because there’s less incentive for them to go out and get it.

“If 500 people want to have the FBI file on a famous dead person, that’s going to be available, and it’s going to be available quickly,” Brown continued. But basic requests about agency activities are pushed into their own pile.

That processing, Brown argued, is made significantly slower by the agency funneling an increasing number of requests onto the “complex” processing track—something the agency said was happening in its response to the Daily Dot’s request about the Slippery Slope game.

The 11,696 FOIA requests received in 2014, the most recent year that’s been cataloged on record at FOIA.gov, is actually down from the 15,664 the agency got in 2009. But the number of open requests it had pending at the beginning of year has nudged up more or less each year—more than doubling between 2009 to 2014.

“You’ve got a system that is predisposed to make it easier to get the sexier, high-profile stuff and makes it harder to get the more nuts-and-bolts administrative thing,” Brown said. “You’ve got a system that is increasingly unequipped to do what it’s supposed to do.”

Failure by design

Part of the problem is technological. Many of the computers the FBI is using to search for this material are from the 1980s and lack graphical interfaces. Outdated technology being a hurdle to government transparency is common across many federal agencies. The CIA only accepts FOIA request by fax machine, for example. In 2013, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, which oversees the NSA among other agencies, was unable to accept FOIA requests for months because its fax machine broke and it had to wait until the new fiscal year to get it replaced.

In the eyes of Ryan Shapiro, an MIT grad student and Harvard research affiliate who has led the charge for increased transparency at the FBI, many of those technological roadblocks were placed there intentionally. “The FBI has constructed a FOIA search protocol that fails by design,” he told the Daily Dot.

Shapiro began looking at the FBI’s disclosure processes while doing research for his dissertation about government surveillance of environmental and animals-rights movements. After years of fighting with the FBI for the documents produced in its investigations, he eventually sued the agency for noncompliance and began seriously looking into transparency issues.

Shapiro argues that the FBI has constructed a system where, after receiving a given FOIA request, the FBI searches for records using what he charges is an “arbitrary, inconsistent, and extremely limited antiquated index that routinely fails to locate records”—meaning that a requester locating what they’re looking for largely comes down to a crap shoot. The FBI is technically able to implement an effective search, but that system is only utilized after a dedicated requester gets frustrated enough to file a lawsuit, which happens in only a tiny percentage of cases.

“The FBI does nearly everything within its power to avoid compliance with the

Freedom of Information Act,” he insisted. “This results in the outrageous state of affairs in

which the leading federal law enforcement agency in the country is in routine and

often flagrant violation of federal law. Even if one does prevail in a particular

FOIA lawsuit, they’ve often invested so much time and energy in it, they

frequently no longer have the resources to take on many of the other cases

they’d planned to. And as a result, government records remain locked behind the

closed doors of the FBI.”

Shapiro said the biggest problem is that there are no consequences for an

agency doing anything in its power to avoid turning over documents. Even if you fight and win all the way to the appellate level, Shapiro said, “[t]here are no penalties for non-compliance with FOIA.”

“The worst-case

scenario for the FBI is, at the end of the four years, you get what you want,” he added. “If the

FBI had followed the law from the beginning, you would have gotten what you

want right away. They don’t lose anything, they only gain. They simply have no

incentive to comply.”

Put in context, waiting a couple years to learn about the FBI’s sheep game may be relatively minor. Waiting 20 years for documents from CENTCOM—something MuckRock recently found out was happening with the agency’s oldest FOIA request—is something far more serious.

Lost in the shuffle

Those long wait times for processing FOIAs can often lead to agencies not being required to disclose information. As Ginger McCall of the Electronic Privacy Information Center told the Daily Dot in 2014, she once waited four years with near total silence on a FOIA request about the TSA’s airport body-scanner technology only to get a note out of the blue from TSA saying she had to respond with 30 days if she wanted them to continue processing her request. When McCall reached out to others who had made FOIA requests to agencies under the Department of Homeland Security umbrella, they reported similar experiences.

People leave organizations as the years go by. People’s phone numbers and email addresses change. It’s easy for a long-unfilled FOIA request to go through a checkup only to end up being shot down when there’s no one left on the other side.

Shapiro hasn’t seen this particular tactic regularly employed by the FBI, but the methods the agency has used to delay his requests are extensive. In his FOIA litigation, a judge granted the Bureau something called an “Open America” stay, which gave the FBI a five-year extension—not to respond to Shapiro’s requests but to figure out how the agency wanted to respond to his request.

Open America stays were intended to be an emergency safety valve for federal agencies that, for one reason or another, are physically unable to comply with a given FOIA request—for example, if there was a fire or a flood in their office that destroyed their computer systems or budget shortfalls resulting in major staffing cuts. However, the rationale for the stay in Shapiro’s case was very different.

“FBI basically said my FOIA research methodologies are themselves a threat to national security.”

“FBI basically said my FOIA research methodologies are themselves a threat to national security,” he said, adding that the agency’s rationale was based on mosaic theory, which argues for government secrecy based on how seemingly harmless pieces of information could be viewed in conjunction with other pieces of information to reveal a picture detrimental to national security. “Therefore, the FBI needs an almost unprecedented Open America stay: a delay on everything for five years so they can figure out how to respond.”

At the end of the stay—which was granted on the basis of an FBI letter that was itself kept secret—the FBI could still legally deny Shapiro’s FOIA request based on a number of exemptions written into the FOIA law.

These types of roadblocks are ones that researchers, journalists, and activists run into with increasing regularity at a time when, ironically, much of the government is making an effort to provide more information available about its activities through public data portals, like how NASA recently announced it would be making all of the scientific studies it funds available online for free.

However, the data being released through those portals is likely the stuff that the people inside those agencies want the public to see—the effective and efficient works of public service that the federal government produces on a daily basis. What agencies are less likely to share are all the documents showing how the public-service sausage got made. If the public wants that info, Brown said, they’re increasingly being pushed to file FOIA requests.

“Unceasingly, you have more people being shunted in this direction, and you have agencies that are refusing to spend the money and resources toward making this stuff updated,” Brown said of the FOIA process. “They have no incentive to. All it’s going to do is make it easier for people to learn about what they’re doing and write an article that says, ‘Why are you wasting money on a game about a sheep?’”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly combined the arguments made in two of Shapiro’s lawsuits against the FBI, one regarding the surveillance of animal rights groups and another about the structure of the agency’s FOIA system.