Last month marked a major milestone: the first anniversary of the publication of the first article based on the documents leaked by Edward Snowden. The former National Security Agency contractor smuggled out a trove of an estimated 1.7 million classified documents not just because of his deep moral qualms about the way the United States government was digitally surveilling its citizens, but also because the lack of transparency within the system made it impossible for those citizens to object to programs they had no idea existed in the first place.

Snowden exposed everything from the widespread monitoring of the cellphone metadata of millions of Americans to the government’s tapping of the private phone of German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Regardless of whether you think he’s a hero or a traitor, there is now an infinitely wider conversation about the role of NSA than ever before.

While the NSA programs revealed by Snowden are largely unprecedented, the secrecy with which they were guarded isn’t. The NSA isn’t the only arm of the government with an institutional tendency to keep its actions, policies, and official documentation away from the light of public scrutiny.

While the NSA programs revealed by Snowden are largely unprecedented, the secrecy with which they were guarded isn’t. The NSA isn’t the only arm of the government with an institutional tendency to keep its actions, policies, and official documentation away from the light of public scrutiny.

In talking with nonprofit groups and journalists at numerous levels—from award-winning investigative reporters at national publications to student journalists who just needed simple on-the-record quotes from an official to avoid failing an assignment—one agency consistently seems to engender the most frustration: the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Created in 2002 as a post-9/11 amalgamation of 22 different agencies, DHS has gained a reputation for opacity. From the ways the department processes Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) requests to providing basic information about its everyday operations, DHS’s issues with transparency are simultaneously wide and deep—spanning across many of its multitude of divisions and running into the very heart its institutional culture.

In the past year alone, DHS was given a failing grade on the Center for Effective Government’s Access to Information Scorecard—the only agency to score lower was the State Department. Last year, its Customs and Border Protection (CBP) division received the inaugural Golden Padlock Award by the nonprofit group Investigative Reporters and Editors for ?refusing to make public the details of use-of-force incidents involving its agents.”

A massive Snowden-esque leak may not solve the transparency problems at DHS, but it’s easy to see why many department observers might welcome one.

?All in all, it’s pretty frustrating”

In June of 2012, Sarah Weber got an email.

Weber, currently an editor at the Daily Dot, was working at a newspaper in Sandusky, Ohio. The message was from a reader pointing out a gaping hole in the paper’s local law enforcement coverage:

There are an awful lot of white and green border patrol vehicles around the Sandusky area. Must be looking for problems on our coastline. Sandusky police have their arrests and other actions printed daily in the [Sandusky] Register. But have never seen one word published about Border Patrol arrests or activities. How come?

– Charlie on Cleveland Road

Weber shared the author’s frustration with the paper’s lack of information about the CBP station that had been set up along the shore of Lake Erie approximately two years prior. By that time, she had spent innumerable hours on wandering endlessly through a maze of bureaucratic red tape simply looking for basic facts about precisely what the 50-some border patrol agents were doing in her community. She started by setting up an interview with the head of the local office. The meeting went well until she started asking for documents about the names and charges against the people who are arrested or detained by local CBP agents, information that’s typically publicly available from law enforcement agencies in Ohio.

After being directed to CBP’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., Weber was told the agency wouldn’t provide names. So, she amended her request, asking for time/date, place, nationality, and reason for each arrest. Eventually, all she got was a mile-high stack of redacted documents.

?We really wanted to see patterns on who was being arrested, but we were never able to get this information,” she explained. ?We were also denied access to information about people being housed in local county jails—which are subject to Ohio public records laws—where [border patrol] had leased cells to house their own detainees. We had no idea how many and how long inmates were housed or what happened to inmates after they were arrested.”

In the end, all Weber could do was respond to Charlie by writing the newspaper had similar concerns and wished the department placed a high enough value about its position in the local Sandusky community to put a premium on transparency:

While we understand the need for national security, having zero access to information on what’s happening in our own back yard seems wrongheaded too. For all we know, Sandusky could be a major illegal immigrant or drug smuggling thoroughfare. Or we’re the squeakiest clean town in these United States. Without access to records on the number and types of arrests federal agents are making locally, we just can’t know either way.

Weber’s experience is far from unique.

?All in all, it’s pretty frustrating to work with CBP,” recounted Andrew Becker, a staff reporter at Center for Investigative Reporting who has spent years reporting on immigration and border issues.

One instance that sticks out in Becker’s mind as being particularly egregious stemmed from a story he’d been working on about the department’s use of polygraph tests as part of its hiring process for new agents. ?I’ve had pending interview requests on that one that have dragged on for months, if not a year,” he said. ?They just basically declined, declined, declined.”

Becker insists that the biggest problem is consistency. He regularly has to file and then fight for the same FOIA requests for the same information over and over again, even it the information was made public the prior year. He has to endlessly jump through the same hoops because, as he sees it, there’s no controlling vision in the agency for releasing information or applying the FOIA law. In addition, he’d regularly give department sources ample time to comment for articles he was writing only to see them wait until the very last minute to make someone available, if at all—and then often mandating that he attribute quotes to an unnamed official rather than anyone specific.

Becker insists that the biggest problem is consistency. He regularly has to file and then fight for the same FOIA requests for the same information over and over again, even it the information was made public the prior year. He has to endlessly jump through the same hoops because, as he sees it, there’s no controlling vision in the agency for releasing information or applying the FOIA law. In addition, he’d regularly give department sources ample time to comment for articles he was writing only to see them wait until the very last minute to make someone available, if at all—and then often mandating that he attribute quotes to an unnamed official rather than anyone specific.

?Certainly it seems like there are many different efforts within the agency to really control the flow of information and in some cases limit information that’s in the public interest,” Becker said. ?How efficiently is the agency run? What kind of internal issues have they had that the public should be aware of? How effective are they in controlling borders? It’s all become very politicized.”

DHS certainly has a history of controlling the release of information in order to minimize potential political fallout. In 2011, the department was embroiled in a scandal stemming from accusations that political appointees were altering the document searches on FOIA requests from media outlets and nonprofit groups deemed hostile to the administration. Congressman Darrell Issa (R – California) released a scathing 153-page report on the topic, sardonically entitled ?A New Era of Openness?” —although the report’s hostile bent likely had more than a little to do with the fact that the political appointees in question were placed there by a Democrat president.

Becker reported on another instance of DHS’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division monkeying with publicly available numbers for political ends. In 2010, he worked on a story for the Washington Post looking into allegations that ICE had intentionally fudged the deportation numbers for the year in an effort to bolster the Obama administration’s case that it was getting tough on border security as a way to convince Republican leaders to come to the table on comprehensive immigration reform.

However, it’s impossible to argue that political considerations are the only reason for the department’s lack of transparency.

For one, it’s important to remember that DHS is only 12 years old. Figuring out how to streamline information requests often requires a cross-cutting institutional memory that may not necessarily exist. At the same time, a lot of the departments within DHS have been around for far longer than that. While the overarching structure may be new, the individuals agencies are likely often still beset by problems of old-outdated legacy technology inhibiting department officials’ ability to do things that would seem simple and commonplace to users of more modern equipment.

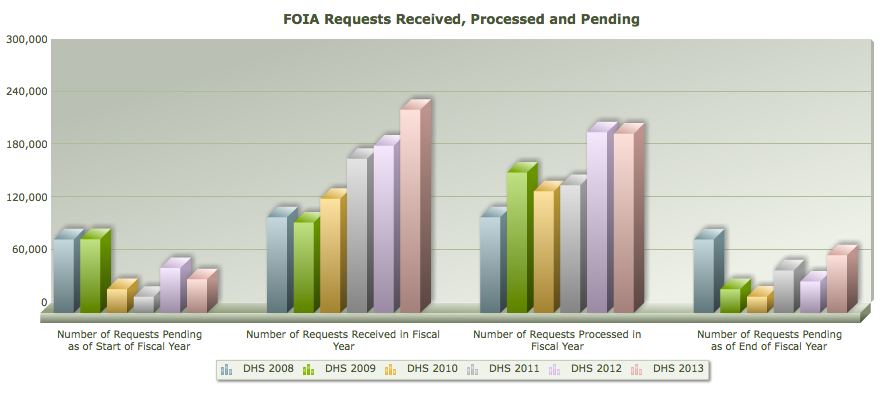

There’s also the issue of the sheer volume of requests. Not only does DHS get the most information requests of any federal agency, but the overall number of those requests have skyrocketed in recent years—approximately doubling since 2008.

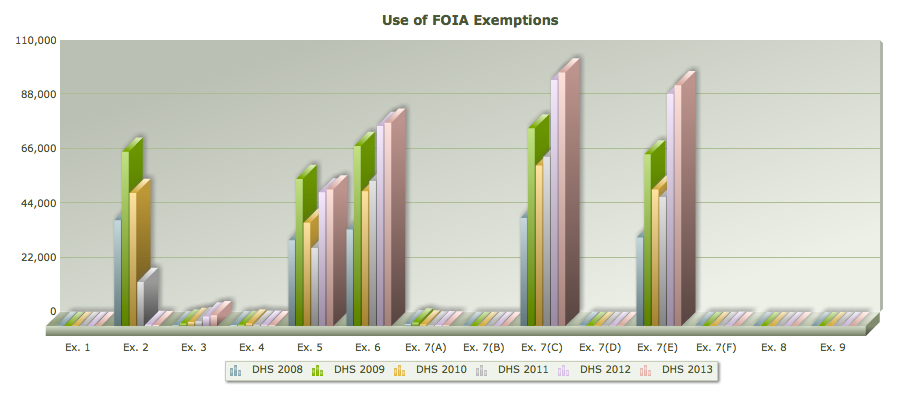

Even so, technical issues can only explain a portion of DHS’s issues with FOIA compliance. Just as the number of FOIA requests have increased, so have the number of times the department has claimed exemptions from having to fulfill those requests.

“From my general experience, most of it tends to be cultural more than simply a lack of resources,” charged Mark Horvit, the executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors, the organization that gave CBP the Golden Padlock Award last year for steadfastly refusing to disclose ?even the most routine, basic information” about the shooting deaths of Mexican citizens by border agents. ?In most places in America, if a police officers shoots someone, you can get reports, you can get documents. This is just refusing to give information about something that’s clearly in the public interest so we know if these shooting are justified or if there’s a problem.”

CBP did eventually did make public a significant amount of information about use of force on the U.S.-Mexico border, but only after months of dragging its heels. The agency released, for the first time ever, the official use-of-force policies not just for the divisions that work at the border, but for the entire department. In May, it even made public a long-anticipated report by the Police Executive Research Forum about agent’s use of deadly force at the border.

Even so, the problem, Horvit said, stems from the department not putting a high value on being transparent with the public:

“Resources are legitimate reason why it might take longer to respond than it otherwise should. But if you’re routinely not making reports available about a certain kind of incident, that’s not a manpower issue. If you’re routinely not answering questions about your actions on a particular issue, that’s not an manpower issue. The same person who refuses to speak could also answer the questions. It’s usually not a function of resources, it’s a function of attitude.”

?Openness in everything except for national security”

Much like DHS itself, OpenTheGovernment.org is a creature of the world shaped by 9/11. The Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit is a coalition of about 90 groups that run the gamut of advocating for everything from public libraries to food safety. According to Assistant Director Amy Bennett, ?every issue in D.C. benefits from government openness. They need to FOIA to see how a program is being managed or they need to see whether or not local streams are being polluted,” and OpenTheGovernment.org does much of that FOIA legwork for them.

The organization was created because, in the aftermath of 9/11, a lot of information that the government used to make publicly came down in the name of national security. People would file FOIA requests for the sort documents they had been easily obtaining for years, suddenly to no avail.

?The George W. Bush administration had a policy where, just because they were legally allowed to withhold something due to a FOIA exemption, the government should take advantage of it,” Bennett explained.

The Obama Administration came into office pledging to have the ?most transparent administration in history,” and, despite the claim being vitriolically disputed by conservatives with some regulatory, things did get better—at least to an extent.

?Obama said he would let out more information unless there is a foreseeable harm [in making it public],” Bennett said, noting that, for a lot of people who frequently file a lot of FOIA requests, the change in policy did make a demonstrable difference.

“Some agencies have really responded well to Obama’s challenge to make the the government more open but they’re generally agencies that are used to working with the public anyway like NASA or the EPA—ones that are really sensitive to what the public thinks.” she added. ?But, in the national security realm, change has been a lot harder. Especially when the message from the top is openness in everything except for national security.”

Even so, DHS is under considerable pressure to at least appear responsible to the public and much of that comes in the form of the department being required to release annual reports on its progress complying with FOIA requests. This reporting is a procedure every federal agency has to go though and contains a lot of information, from the number of requests each agency processes to a record of its oldest, unanswered complaints.

Ginger McCall, a director at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, charges that not only does DHS have a tendency to take a wide interpenetration of the exemptions permitting the agency to avoid disclosing information, but it also engages in some fairly shady practices designed to make it seem like officials are more responsive to public information requests than they actually are.

She recalls an instance when her organization, which typically files just over half a dozen FIOA-related lawsuits against various government agencies each year, was attempting to learn more about the airport body scanners program being run by the Transportation Security Agency (TSA), which sits under the umbrella of DHS. She made the FOIA request and began waiting for the agency to turn the relevant documents. She ended up waiting four whole years before TSA officials finally got back to her. They said that she had 30 days to let them know if she was still interested in getting the information or else they would summarily close the request.

She recalls an instance when her organization, which typically files just over half a dozen FIOA-related lawsuits against various government agencies each year, was attempting to learn more about the airport body scanners program being run by the Transportation Security Agency (TSA), which sits under the umbrella of DHS. She made the FOIA request and began waiting for the agency to turn the relevant documents. She ended up waiting four whole years before TSA officials finally got back to her. They said that she had 30 days to let them know if she was still interested in getting the information or else they would summarily close the request.

McCall recalls being shocked by the sheer gall of it. She had been waiting years for a response and then was told that she only had the window of a few weeks to respond. ?After this occurred, I reached out a few other groups [that regularly file FOIAs with the agency] and asked if DHS had done similar things to them,” she said, ?and they had.”

What’s likely going on here, explained Bennett, is that this technique is a relatively simple way to DHS to clear it backlog of old FOIA requests.

?They take the requests that are at the very bottom of the queue and send out emails or letter saying that if we don’t hear back from you in 30 days, we’re going to consider this request closed,” Bennett said. ?But, if a few years have elapsed, maybe the person who made the request in the first place changed phone numbers or doesn’t work there anymore. All DHS has to do reach out once, wait a month, and the close the request like something was actually done.

?It’s taking advantage of the statistic of making yourself look good without really putting in the work to make information available to the public.”

?A lot like feeling around in the dark”

There’s a fairly convincing counter-argument to charges about the DHS’s opacity. The department’s primary mission isn’t to tell the American people what its doing—its primary mission is to keep the American people safe.

?DHS officials are intensely aware that they have national security and law enforcement responsibilities and those often times are in the driver’s seat over the urge to be more open,” Bennett said.

However, it is in those instances where the department’s goal of protecting the life and property of American citizens infringes on that third leg of that constitutional stool—liberty—that transparency becomes important.

Last year, Sarah Abdurrahman and her family were detained at the U.S.-Canada border on the way back home after attending a wedding in Toronto. They were held in a pair of facilities along the border for hours, repeatedly interrogated, had their personal effects and electronic devices searched—all the while being kept kept in the dark about why they were being held.

While most people subjected to this type of treatment have little recourse, Abdurrahman had a weapon in her back pocket: She is a producer at the NPR radio show On The Media. Abdurrahman’s story, a recounting of her experience and recording of her largely frustrated attempts to figure out the reason for her detention, anchored a full hour-long show about the difficulty almost universally experienced attempting to get information out of CBP.

?I never ultimately got a sense of why my family and I were targeted,” Abdurrahman told the Daily Dot. “I am of Libyan descent, so maybe it’s because Libya has been in the news a lot over the past couple years. But it’s a lot like feeling around in the dark.”

Even after the show was aired, she never heard a peep from anyone at CBP or DHS. Who she did hear from was the public.

“We had a lot of people calling and writing in and saying that something like that happened to them,” she recalled, noting that the story triggered a wave of response that was almost universally positive. ?Not knowing the reason behind being targeted is what makes this so difficult. You don’t know if this is just going to be the norm from now on. If this is going to happen every time I try to leave the country. Am I going to be put on the no fly list? Am I going to be detained indefinitely without warning? It’s worrisome because you don’t know what could be next.”

Part of the show involved the creation of a tool called Shed Light on DHS, which allows people to easily contact their elected representatives and put pressure on them to improve transparency at the department.

Abdurrahman says she doesn’t think it’ll make a huge difference overnight, but convincing lawmakers that their constituents think keeping America safe and letting Americans know precisely how DHS keeping them safe shouldn’t be mutually exclusive.

It’s something that Hovit, whose group doles out the Golden Padlock award, noticed when he started tallying up nominations for the award.

?The other finalist last year weren’t law enforcement agencies at all. They consisted of a job creation agency in Ohio, a transportation agency in New Jersey, the tax commissioner in Georgia and the Center for Disease Control,” he said. ?This year’s list, which hasn’t been made public yet, isn’t dominated by law enforcement agencies either.”

For its part, DHS officials insist they’re doing the best they can. “Openness and transparency between the Department of Homeland Security and the public are critical to our security mission,” agency spokesperson S.Y. Lee wrote in an email to the Daily Dot. “DHS is committed to accountability and being responsive to all FOIA requests in a timely manner.”

Photo via Jay Sekora/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed