When Renee Hess attended her first NHL game, at Anaheim’s Honda Center in 2016, she was impressed with what she encountered — save for one troubling detail.

“When I finally went to my very first game in person, the aesthetics were amazing,” she recalled. “I mean, the cold rink, the sounds of the puck going across the ice, the energy in the crowd was something I had never felt before. But I realized pretty immediately that I was the only Black woman in this space.”

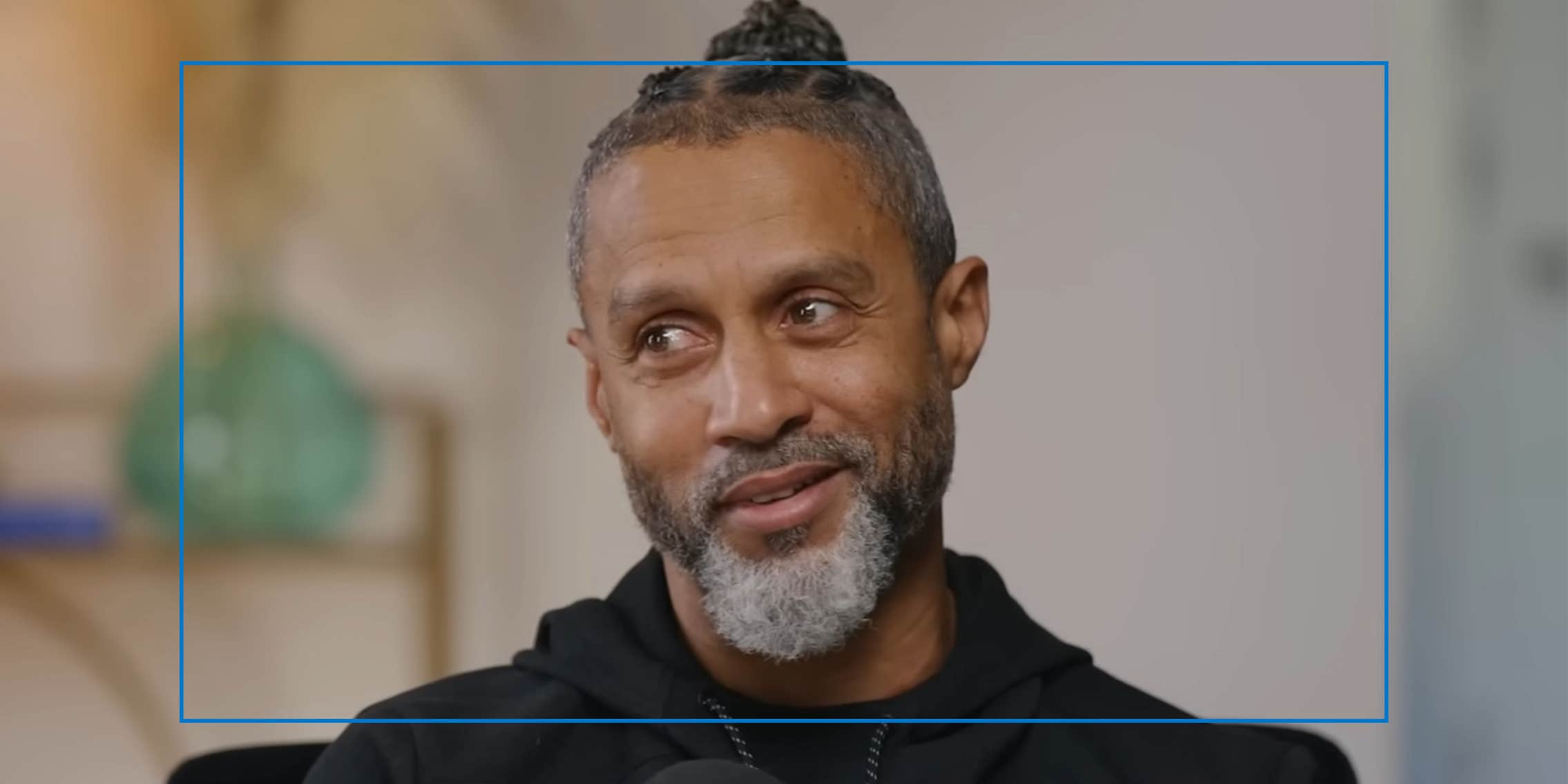

Hess, an educator, writer, and self-described “professional arguer,” quickly wondered how she could change that.

“It was a little nerve-wracking to walk into a very white space and be not only one of the few women but also one of, if not the only, Black woman in a hockey arena that didn’t work there,” Hess said. “As I was developing my love of the game, I kept coming back to, ‘Where are all the black girl hockey fans?”

Hess set out to change things, and approached it like the academic she is — starting with a survey. Hess created a Google survey and distributed it on social media in an attempt to engage people of color who were also hockey fans, whether they were lifelong fans of the sport or newcomers to the game like herself. What she found was both disturbing and sadly predictable.

“It became evident that there were Black women hockey fans, but they just didn’t feel comfortable going to games,” Hess told Sportsnet in a February 2020 Q&A article. “A lot of them, they had experienced micro-aggressions when they were involved in hockey events, when they were on hockey social media, stuff like that. So they didn’t want to go to games. They didn’t have anybody to go to a game with, for whatever reason.

“And I started thinking, ‘Well, I kind of feel the same way — maybe we could get together and go see a game together.’ There’s power in numbers, right?”

‘We’re all united under this love of hockey’

Hess organized a group meetup of hockey fans — all women of color — she had met online with Hess flying out to the East Coast from her West Coast home base. The group attended a Washington Capitals game, the impetus for what would become Black Girl Hockey Club, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit group that advocates to make the sport more inclusive of Black women, and their family, friends and allies.

“We went to that first meet up together in Washington, D.C. in 2018, and I was surrounded by 45 Black women, their friends, their family, their kids,” Hess said. “We came together in a hockey arena, in that space but it really showed all of us that very first time that we come from so many different backgrounds, but we’re all united under this love of hockey — and that with our different backgrounds and with this community, we could actually build something that was more than just a fan group, more than just getting together and going to games.”

Today, the BGHC has a membership of over 500 as per the Black Girl Hockey Club Wikipedia page, and around 8000 subscribers to its monthly newsletter according to the International Ice Hockey Foundation. The club hosts events across North America, including meet-ups where black players and fans can discuss the issues of inclusion and diversity in the game. Best of all, it has begun changing the faces Hess sees at the games.

“We like to go to games together and just make space in physical hockey arenas for black women,” Hess told BBC’s Sounds. “It’s so much fun going to a game with Black Girl Hockey Club. We get out there, we have a good time and we just like to enjoy ourselves.”

‘The other side of the nerd coin’

Hess’ own relationship with the game wasn’t formed in childhood, unlike many lifelong NHL fans. “I had just graduated with my master’s degree,” she recalled. “I was kind of looking for something to occupy my time the way that graduate school occupies your time and I decided to hop into a new fandom.”

She added, “I wanted to do something unique, I wanted to do something that none of my friends were doing and I had a girlfriend that I knew from, she has a popular culture website that she runs and we had kind of worked together writing about film and television but I knew she was also a sports fan. I reached out to her and said, ‘You know, I’m kind of thinking about sports as a fandom, what does that look like?’”

“Sports fandom is just the other side of the nerd coin,” Hess reasoned. “I mean, there’s statistics, there’s art, there are fan groups … these are fan boys! And girls! So, hockey kind of came into my purview that way and I went about it the way any good geek does.”

Hess initially was considering writing a book, revealed, “I wanted to read about Black women in hockey because there was no information out there and if me, a Black woman hockey fan, was having a hard time finding it, I can just imagine a traditional white cis male hockey fan would not have any idea about Black women and the contribution that we’ve had to hockey and what we’re doing right now in hockey.”

Her research quickly began to gain momentum as a force for advocacy within the sport. By 2019, she’d filed Black Girl Hockey Club filed for non-profit status to grant scholarships to young Black female players.

A new purpose, borne of tragedy

Then, the events of the following year — including the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery catalyzing Black Lives Matter protests nationwide — quickly reframed the club’s outreach.

“Folks that look like me started taking to the streets and started talking about advocacy in all walks of life, in all avenues,” Hess recounts. “And I kind of had to sit down and figure out what I wanted to do with this amazing club that we had just started. How could we engage in those same types of conversations? How could we engage in advocacy and social justice issues in hockey? It’s such a random, weird place to try and do that, but it’s very obvious that it’s necessary to have these conversations, again, in all aspects of sports and in our work and our personal lives.”

In May 2020, Hess took to Instagram live in a post she refers to as her “manifesto,” laying out the club’s new direction. This led to the launching of the group’s “Get Uncomfortable” campaign, a “comprehensive set of recommendations on how all entities involved in hockey, at all levels, can meaningfully contribute to the movement against discrimination and oppression of BIPOC communities in society.”

”It was a success,” Hess declared. “A lot of people were interested in talking about these things and I’m really so glad for it, that we’ve been able to kind of on one hand enjoy just getting out in public and going to hockey games and helping other families enjoy hockey but also on the other hand address these very serious issues that black women are thinking about and dealing with all the time.”

But Hess’ true legacy may likely be the difference she is making in the lives of young black players throughout North America.

“Hockey is expensive!” she exclaimed. “The gear is expensive, playing for a team is expensive, the USA/Canada hockey fees are expensive and we sat down with a hockey mom and we’re like, ‘Okay, so how much does it cost?” And she told us probably, bare minimum, five grand! Just to get a girl on a team, not including gear or tournaments or anything like that.”

“We have a $5,000 scholarship, we have a $3,000 scholarship, and a $1,000 scholarship,” Hess related. “And in the 2022 season, last year, we gave away 30 scholarships for $62,000 [total]. I don’t know how we did it, knock on wood, we’ve got some amazing donors that helped us hit that goal.”

Chicago resident Orane Blake, father of Victoria Blake, a recipient of one of the BGHC’s $2,000 scholarships, told WGN the difference the club has made in his daughter’s life as a player. “It creates a sense of identity among the girls because they don’t see themselves represented in the community of hockey. Being able to give them that visibility [that says] ‘Hey, you girls are not that different. There are many other girls, just like you and you can aspire to be just like them.’”

“That’s our goal,” Hess noted, “ just keep it pushing, building chapters all across the world and engaging with players and families and fans who want to address some of the issues that we’re addressing, to find that community space we’re building and to really facilitate a shift in hockey culture.”

She added, “That’s what we’re doing, we’re changing the world, right? One little girl at a time.”

See more stories from Presser – examining the intersection of race and sports online.