BY DANIEL HARRISON

Ron Hose strikes an unusual figure in the Philippines. Soft-spoken but emphatic, he doesn’t so much out as seem like he would fit in well somewhere else. San Francisco is where you’d naturally place Hose, or maybe in his home country Israel—somewhere that’s typically home to a startup enterprise.

And yet, Hose spends most of his hours working away in a 200-square-foot room on the 12th floor of an unglamorous, fairly old-fashioned office block in the Philippines. He can be hard to read. He shuns the sort of reverence and adulation that most disruptors crave. Not even his closest colleagues or his assistant could tell me his age or why he abandoned the West Coast.

“Do you know what we are all about here? Do you understand what it is we are trying to do?” Hose says, sounding vaguely irritated, in the hallways of his office building, perched on the couch. “The greatest mistake that people make is in thinking of unbanked people as not having a bank account because they are poor. It’s the other way round. Only 30 percent of this country has a bank account; most people have nowhere to keep their money. We are actually going to change all of that.”

Coins, Hose’s latest startup, is a payment-processing company based in the Philippines that allows people to make overseas (or local) payments at a fraction of the cost Western Union charges using Bitcoin or other comparable virtual currencies. Founded in 2013, the company has a second office in Thailand cofounded and managed by Topp Srupsrisopa, an Oxford graduate and former central bank economist.

Hose has reasons to be optimistic, if his personal track record is anything to go by. He graduated at the top of his class from Cornell University before cofounding and serving as CTO for Tokbox for a bit, which rapidly blew up into a multimillion-user video-conferencing company. By the end of its first year of operations in 2010, the company had completed all but one of its funding rounds, raising $26 million.

“There are 100 million people in the Philippines alone, many of whom are making payment transfers at least once a month.”

In today’s white-hot VC funding climate, that might sound somewhat average. But back then, in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis, it was all but unheard of. Then, soon after cashing out in a $30 million sale, Hose cofounded another venture that became an instant success, too—a VC fund dubbed Innovation Endeavors, made famous by the involvement of Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

By any reasonable measure, Hose seems like he should be brushing shoulders in Silicon Valley.

“It’s not all philanthropy,” he makes clear. “We plan to—we’re going to, even—make a lot of money doing this. The market is huge and ripe for disruption: There are 100 million people in the Philippines alone, many of whom are making payment transfers at least once a month.”

Taking Hose’s ambitions into account, that means there are 40 million potential customers in the Philippines alone. In Vietnam, which boasts a larger population—and which the company entered in early 2015—that number is about a fifth larger still.

Hose isn’t the only one with an eye toward the Philippines. A growing number of young entrepreneurs are turning the sovereign island country into a hotbed for disruptive technologies.

An isolated hub

The Philippines’ more than 7,000 islands huddle together in isolation like tropical polar icecaps planted high with exotic fruit trees, hundreds of miles out in the middle of the western Pacific Ocean. Geography alone makes it one of the unlikeliest places on the planet to be a hub for the tech industry. Any yet, the Philippines is a veritable melting pot of early-stage tech entrepreneurship.

Here, crowdfunding is de rigueur for everyone from garage bands and would-be independent movie producers to rejuvenated basket-weaving manufacturers in remote agricultural farmlands far from anywhere. Cryptocurrencies really do get used by the locals as a mechanism for fee-free exchange, I found during my travels. There are major financial institutions which Coins has enlisted as partners.

“The youngest generation already is paying electronically, where it’s convenient to do so,” Hose notes.

“For many poor people here, they can’t afford to make international calls but they have family living and working overseas.”

The Philippines might be poorer than most of its Asian neighbors, but it’s also much more populated than any of them besides China. Manila, the capital city, bustles with an unmistakable millennial vibe. Every weeknight crowds of career-hungry 20-somethings gather somewhere high up in one of the city’s less than five-year-old skyscrapers at a startup meetup designed to foster new businesses.

It seems like nearly everyone has an idea to pitch. Coins Marketing Manager Christine Aguilar, for example, is developing is a Skype-like app that lets you call into any phone in any country in the world for free after you have listened to an advertisement before the call. What makes it unique is that it syncs to your phone so when you dial via the app, the caller ID will show up on the recipient’s phone as your regular phone number. On the way to the meetup, she runs through a brief demonstration, and it works quickly and with a clear line.

“For many poor people here, they can’t afford to make international calls, but they have family living and working overseas,” she explains, before dialing my U.K. cellphone. “Now all they have to do is listen to one ad, and then they can talk to their family in America, in Hong Kong—simple as that.”

A crowdfunded economy

Back in 2010, Patrick Dulay faced a dilemma: Should he go back to the Philippines, keep living in France, or possibly journey to America after graduation?

“I realized that ultimately, I would be taking a mediocre job in Europe, and living a mediocre life,” recalls Dulay, who’s from a class above the regular white-collar office staff that form the burgeoning section of Philippines’ new middle-class consumers. “It was at that moment that I realized I had to go back and help my country.”

The timing was ideal. While the country’s GDP growth had held firm on a trailing 10-year basis, at 2.5 percent for the entire subprime mortgage crisis, since 2009, more venture capital firms had opened doors than at any comparable point in the country’s history.

A lot of that boiled down to Dulay and his peers coming home or rising up and sharing ideas, progressively and interactively seeking alternative ways of trying to think about the future of the country. It was out of a meetup that Dulay founded the Spark Project in the middle of 2013. The crowdfunding site hopes to empower locals to return to the handmade crafts that once powered the community.

During the manufacturing boom of the 2000s, the Philippines economy largely got left behind. Communities that used to manufacture baskets, clothes, furniture, and a host of other items for export lost out as Vietnam, Indonesia, and large parts of China were industrializing at a breathless pace. They were making vast amounts and ranges of products with the help of high-tech equipment, globally financed manufacturing plants, and sophisticated logistics software to transport it thousands of miles away, and they were doing it for cheaper than ever before. The turbulent political climate and domestic banking system only complicated matters further.

One place especially hard hit was Dulay’s hometown of Bataan, where locals once prided themselves on making bags from the unique fabric that could be produced by the varieties of plants particular to their region. At one point, up to 10 percent of the world’s backpacks had been made in Bataan. But with an industrialized Asia producing copycats at cheaper prices in higher quantities next door, Bataan bag makers largely turned to piracy, copying Chanel and Louis Vuitton, as well as many American brands like Donna Karan, to satisfy a rising illegal demand for faux goods.

“Gian (Carlo Rosales) said to me: ‘We have resources and skills; let’s tap them so they don’t have to make fake bags but can concentrate instead on original and Philippines-made high-quality bags,’” Dulay recalls.

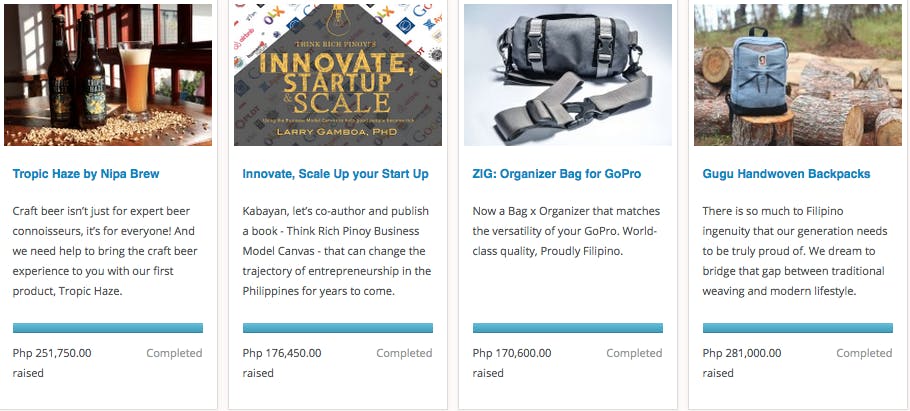

Rosales’s CarrierPro, a bag that could carry GoPro camera equipment, became one of the Spark Project’s earliest successes. Since then, two other bag makers have also raised a total of around $30,000 U.S. at the site to produce their own designs; that’s significant funding in the Philippines.

Other beneficiaries of the Spark Project include a tour company that offers trips to a former leper colony that is now a (disease-free, obviously) scenic island; various other clothes makers from local areas of the Philippines, where access to mainline transport is cut off; and a girl who received funding for her study in Denver, Colo., over a two-month period at the national Camp Up with the People.

“Spark Project is my response to helping the country somehow through promoting entrepreneurship,” explains Dulay. “At least for me, with my background, I can create significantly more impact as a citizen doing business rather than someone elected to political office.”

The path forward

Ron Hose didn’t attend the company’s Bitcoin 101 event on this particular evening—he had a plane to catch to Singapore—but he gave me a full demonstration of Coins’ product.

Essentially, Coins is an app you can download from the company’s website, Coins.ph, that connects you to a payment device—be it a bank, a credit card, or a cellphone top-up card. From there you can then instantly transfer over cash to someone’s real bank account or, if the recipient doesn’t have an account of their own, to a Coins wallet. At that point, the funds can be cashed out in the same way that Western Union payments are—by physically visiting a participating bank teller. Except it’s nowhere near as expensive.

“I can create significantly more impact as a citizen doing business rather than someone elected to political office.”

Hose remains wholly convinced of Coins’ potential to counter Western Union. I touched in with him for a brief chat again recently to ask how plausible it was to overcome such a hugely disadvantageous starting point.

“It takes a long time to get from technology to product, to market acceptance yes, and, market penetration,” he acknowledged via Skype messenger, typing into our virtual conversation every bit as breathlessly as he was speaking to me person weeks before. “But there will be an inflection point where adaption will start zooming up and the apps themselves can be deconstructed. …

“If that data is all open and free, then you could have competing engines. So it’s basically breaking down the value chain and the more archaic the industry (e.g., shipping, logistics, finance), the more valuable can be reclaimed.”

What Hose is saying is classic disruption arts: The less of the old, tired, heavy infrastructure you have weighing your core economic processes down—shipment by shipment, SWIFT payment by SWIFT payment—the infinitely easier it becomes for you to adopt the new lighter weight improvement (the “app”).

He stresses that its technology can run of any protocol or development agenda, not just Bitcoin. “I don’t even know the price of Bitcoin; I don’t need to. There are any number of technologies we can run the thing off; it’s just that the [Bitcoin] blockchain is the most convenient for now.”

At that point, Hose signed off with what might have been his most revealing statement:

“It still requires productization, most notably, building trust (identity + peer review) system not just value exchange, but yes, decentralization = making the services truly competitive. i gotta run :)”

There’s a lot to unpack there—the juxtaposition of productization and building trust, leveling the playing field through decentralization—and all of it gets to the root of what’s happening right now in the Philippines.

Hose and his contemporaries are looking for new ways to solve old problems and build something bigger than themselves, to re-energize the area through the principles of disruption.

Daniel M. Harrison is the author of Butterflies: The Strange Metamorphosis of Fact & Fiction in Today’s World.

Photo via Kai Lehmann/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)