It’s easy to get excited about internet voting.

Social media, Skype, online banking—these types of tools and services have expanded our voices, connected us the world over, and added convenience and efficiency to our lives. Who wouldn’t want to see elections benefit from these kinds of advances?

But internet voting isn’t online banking or video calling or tweeting. Voting is a special activity, and trying to do it online poses special problems, most of which security researchers don’t yet know how to solve.

“The technology is just too insecure to entrust such an important right of American people to that insecure technology,” said Bruce McConnell, global vice president and cyberspace program manager at the East West Institute and former deputy under secretary for cybersecurity at the Department of Homeland Security.

“The technology is just too insecure to entrust such an important right of American people to that insecure technology.”

While at DHS, McConnell studied internet voting to understand the national security risks it might pose. He talked to experts at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and learned that “our own internal government technical experts felt pretty strongly that this was not such a great idea.” He went to the Pentagon and talked to cybersecurity policy staffers in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, “who agreed with us that this was not the best use of DoD resources, to promote internet voting.” (The Defense Department had experimented with internet voting for overseas service members, but a security audit exposed serious problems and the project was canceled.) He talked to the companies that sell internet voting technology, but “they were not really interested in talking to me in any detail, other than just to say, ‘Everything’s fine; our stuff is secure.’”

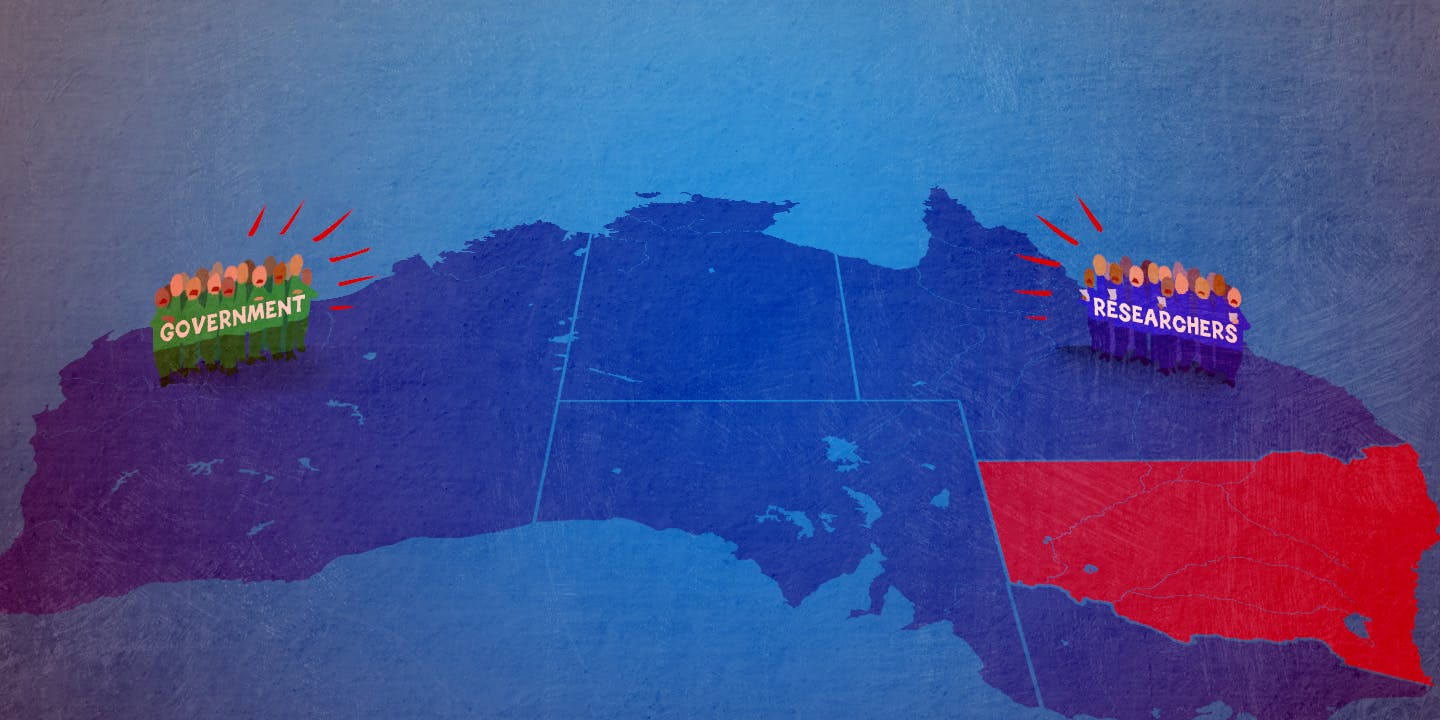

McConnell’s experience reflects the broader dispute over internet voting. While independent researchers point to major flaws in proposed and deployed systems, vendors insist that nothing is wrong. Election officials, meanwhile, have tried to make it work. But a decade of test cases, from Washington, D.C., to New South Wales, Australia, along with a mountain of technical research and task force reports, suggests that there is still much work to be done.

“We do not know how to build an internet voting system that has all of the security and privacy and transparency and verifiability properties that a national security application like voting has to have,” said David Jefferson, a researcher at the Center for Applied Scientific Computing at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and vice-chair of the board of directors at Verified Voting.

Herein lies the problem.

Pushing past paper prompts a paradox

The paradox of ensuring both verifiability and anonymity in internet voting has frustrated security researchers for decades.

The history of elections in the United States—to say nothing of how elections have proceeded in other, less democratic countries—demonstrates the importance of maintaining the secret ballot. In order to rule out corruption to the greatest extent possible, elections must feature what Stanford University computer science professor David Dill, a Verified Voting board member, calls “non-coercibility, or receipt-freeness,” which is the inability of a person to prove to anyone else how they voted. “I should be able,” Dill said, “to lie to them about the presidential candidate that I voted for, to defeat their bribing me or threatening me to get me to vote a particular way.” If bribery is possible, it will happen. Thus, in this most important of political activities, bribery must be made impossible.

But election administrators lose something when their internet voting platforms disentangle ballot data from the identity of the people casting those ballots. “When you have the requirement for anonymity,” said Daniel Zimmerman, a security researcher at the technology firm Galois, “you have a lot less audit data that you can work with.”

Internet voting advocates often say things like, “If you can bank online, you should be able to vote online.” But banks provide receipts for transactions, letting every party verify that deposited or withdrawn money went through the system correctly. You can ask your bank to investigate a bad transaction, just as your credit card company might call you to verify a suspicious one, but only because money tied to your identity is tracked through the global financial system.

Unlike in banking, where fraud is detectable because money either lands in the appropriate place or disappears, and in paper voting, where physical evidence must be tampered with to rig the results, technology lets people do things while leaving literally no trace. “The system goes to great lengths to destroy the link between my name and the ballot that I cast,” said Dill. “That’s a property that’s special to elections that almost no other system of electronic transactions deals with in the U.S.”

Vanessa Teague, an electronic voting expert who teaches computer science at the University of Melbourne, put it another way in an email to the Daily Dot: “Either privacy or correctness could fail without that failure being apparent, even to the people running the system.”

It is possible to hide evidence of tampering with paper ballots, but doing so is often clunky and requires a team of conspirators with access to far-flung physical resources. “The more wrong it is, the more noticeable that would be,” said Mark Ryan, a computer security professor at the University of Birmingham. “That’s a feature we don’t have with computers.”

“If you’ve got an electronic voting machine,” Dill said, “somebody enters a vote, it displays the same vote, everything looks great, and then the voter says, ‘Cast this,’ the voting machine can change the record, either through errors or because of tampering, and there’s really no way to detect that. Anybody who goes back to look at the electronic ballot will see a perfectly legitimate ballot which happens to be different from how the voter voted. And since the secret ballot demands that the link between the voter’s identity and that cast ballot be broken, there’s no way to go back and check.”

As internet voting advocates point out, this problem is not unique to voting. Computers run stock markets, banks, schools, hospitals, charities, and defense contractors, and news websites. But in no other aspect of life besides voting does society demand complete anonymity. “The tricky bit for people to grasp,” said Joe Kiniry, the research lead for Galois’s verifiable-elections program, “is that the set of requirements around elections look and taste different than any other modern online system.”

The warning in a 2001 report from a workshop sponsored by the National Science Foundation remains true today: “Remote internet voting systems pose significant risk to the integrity of the voting process, and should not be fielded for use in public elections until substantial technical and social science issues are addressed.”

The grim state of existing systems: “It’s like the dumbest possible choices are being made”

The state of most currently deployed internet-voting systems gives security researchers heartaches. To understand why internet voting isn’t yet ready for primetime, consider the separate but equally pernicious sets of dangers facing “voters’ machines”—your phone or computer—and election servers.

Malware runs rampant across the internet, and it is growing in volume and sophistication. According to Panda Security, 27 percent of all known malware first appeared in 2015. More than a third of all computers were attacked at least once last year, according to Kaspersky Labs. And nearly three-quarters of legitimate websites are running flawed code that could expose their users to attack.

It’s well known that malware lets thieves pilfer people’s financial and health data and helps hackers lock users’ files until they pay a ransom. But criminals can also use malware to tamper with the process of internet voting—and the more places adopt internet voting, the more enticing it becomes for a hacker to write malware aimed at interfering with specific platforms.

“Maybe the Chinese, for example, would want to influence who is elected as the next president of the United States.”

This interference won’t be limited to lone script kiddies, activists flamboyantly trying to highlight the system’s flaws, or anarchist groups like Anonymous. Given what researchers say about the ease of covertly tampering with some online-voting systems, foreign governments are likely to want in on the action too.

“Maybe the Chinese, for example, would want to influence who is elected as the next president of the United States,” said Ryan. “They’re a very powerful adversary, obviously, so … it’s perfectly feasible for them to spread malware on voters’ machines that would be very hard to detect but that would change the way you vote—again, in a way which is undetectable.”

“To me,” Ryan said, “the threats are huge, because of the power of the potential adversaries and because of the weakness of machines that are in the possession of ordinary users.”

Given the stakes, McConnell, the former DHS official, said that “online or electronic submission of marked ballots would create a national-security vulnerability.”

Vote-tampering malware could take many forms. A surreptitiously installed program might detect packets that contain vote data—by looking at technical details like where the traffic is headed or what digital fingerprint it carries—intercept the packets, and replace them with packets that constitute a forged vote. An infected election-office website might point voters to a fake voting program that, once downloaded, forges ballots before sending them to the office. Even if voting takes place directly on the election office’s website, many attacks exist—and some have been revealed—that can poison the HTML or JavaScript code that the website runs.

Malware is one of the biggest problems with internet voting, and unlike the paradox of anonymity and auditability, this problem has no theoretical solution. Viruses and malware are widespread, and security programs are imperfect. The makers of antivirus and antimalware apps cannot hope to keep up with the rising tide of new variants. “Even if we had perfect users,” Dill said, “the whole virus thing is a state of ongoing war.”

From Sony Pictures Entertainment to the Office of Personnel Management, data breaches and cyberattacks have grown much more common in the last three years. But server-side attacks on election offices are nothing new. In fact, this technique dates back to the earliest days of the internet.

On April 27, 1994, South Africans went to the polls for the country’s first election since the end of apartheid. Nelson Mandela, the formerly jailed freedom fighter and leader of the African National Congress, won a decisive victory, with his party receiving 62.7 percent of the vote. But unbeknownst to all but a select few election observers and administrators, a hacker breached the election commission’s computer network on May 3, 1994, reducing the ANC’s vote count and increasing the tallies for the country’s three right-wing parties. A U.N. computer expert eventually caught the tampering, forcing election officials to rely on a manual backup tally that delayed the release of the results for two days.

For 16 years, none of the people who knew about the breach said a word. The attack only came to light when Peter Harris, the chief of the election monitoring office at the time, wrote a 2010 book about the election.

J. Alex Halderman, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Michigan, said that the way election officials handled the incident was illuminating. “It shows that the likely instinct of the election organization, if a problem is detected, is not to be transparent about it,” said Halderman. “There’s no incentive to be transparent about it. The incentive is to make it look like everything is operating correctly, or at the very least, to not let on that the reason for any problems [is] a successful attack, because that just reduces voter confidence and potentially could destabilize a country’s government, if it leads to doubt about the leadership.”

In addition to data breaches that change results, internet voting systems are vulnerable to distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that flood election servers with garbage traffic to slow them down. When the servers are running slowly, voters can’t vote, and the entire process must either be delayed or canceled. This happened in Ontario during two leadership elections for the New Democratic Party. In the 2012 incident, according to Jefferson, the company running the platform for the election officials, Barcelona-based Scytl, spent a considerable amount of money trying to track down the perpetrator and came up empty.

Despite these obvious problems and the warnings of many American security researchers, instances of internet voting continue to pop up around the United States. Utah Republicans opened up their March 22 presidential caucus to online voting, despite warnings from computer-science experts. As expected, things didn’t go so well: Many people had trouble registering and voting. “Several of us did a lightweight analysis of it remotely, to see how it was built and deployed and this sort of thing,” said Kiniry. “And we found that they were using technologies that even modern Web programmers stay away from.” The server’s content management system ran a software version with known flaws in the scripting language PHP.

“It’s like the dumbest possible choices are being made by some of these companies with respect to deployed technology that should be mission-critical!” Kiniry said, his voice conveying how dumbfounded he was. “And yet, they’re using what they know. And you can’t blame them for that, if somebody’s willing to pay for it. But it’s going to cause them and American voters a world of heartache some day.”

Kiniry and Zimmerman, who coauthored a July 2015 study of internet voting systems, were sharply critical of systems that offered voters and election administrators a false sense of security. When they spoke to the Daily Dot together from their office, Kiniry pointed to internet voting platforms in Norway, Estonia, and New South Wales in Australia, as well as products made by the company Everyone Counts, as “systems that pretend to give you evidence that … your vote was recorded correctly but in fact are duplicitous.”

“All those systems start to use the same terminology we do,” he added, “but they embrace and extend that terminology and then give you fictitious information that helps you feel good about the security of your election, when in fact it’s all a fiction.”

Famous audits and their lessons

“Every time competent people have had a chance to either attack the voting systems in a demonstration circumstance or to study them in the laboratory,” Jefferson said, “we have found deep and profound flaws.” Several recent examples of flawed internet voting platforms lay bare the problems facing the industry.

In 2010, the city of Washington, D.C., planned to let citizens vote online in the fall midterm elections. The city government staged a mock election to test the voting platform and asked technically sophisticated observers to try to hack the system. Halderman and his students at the University of Michigan took up the challenge. “I don’t think they believed it could be done,” he said, “but our team was able to, in about 48 hours from the system going live, be in complete control of the election server and change all the votes. So that was a rather dramatic result.”

What’s more, Halderman said, the flaw amounted to a single line of code in which double quotation marks had been used instead of single quotation marks. “That was enough to let a remote attacker from anywhere in the world change all the votes,” he said. “That’s one of the disturbing things about online voting—that very small, subtle mistakes can lead to total compromise, and potentially not detected compromise.”

To see whether the D.C. government would catch the problem on its own before real voting began, Halderman’s team left a “calling card” in the system. They changed the code so that, every time someone voted in the mock election, their computer played the University of Michigan football team’s fight song. City officials still took two more days to find it, Halderman said, “and even then, it was only when someone else complained about the music that played at the end and said it was distracting.”

“Oftentimes, when systems are put into some sort of test mode, it’s been fairly easy for students to find a way into [those] systems,” said Charles Stewart, a political science professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, citing the D.C. example. “That has led folks to wonder about whether online voting is ready for primetime.”

For Dill, the thing that should really scare people about internet voting vulnerabilities is how simple many of them are. “The things that Alex Halderman did … were not exactly exotic attacks,” he said. “That’s the kind of thing that thousands and thousands of hackers around the world are routinely doing to servers.”

Another troubling example is the Estonian internet voting system, which Halderman, who co-authored a security analysis of it in 2014, called “pretty primitive by modern standards.” Halderman divided the problems into two buckets: the design of the voting system and the security of the voting infrastructure. The voting system itself, he said, is woefully inept. “The systems that researchers have developed, most researchers say, are not nearly ready for practice but are still miles ahead of what Estonia has actually been deploying.”

The election office’s in-house security measures weren’t any better. “I got to observe the processes that they went through, and there were just—it was just quite sloppy throughout the whole time,” he said. “There were various things they were doing that were clearly not good practices from a security standpoint and would have exposed them to potential attack.”

There is no better illustration of how acrimonious the internet-voting debate can get than the security audit that Halderman and Teague performed on the Scytl iVote system that New South Wales, Australia, used in 2015. When voting began, the two researchers examined the public aspects of the New South Wales project, the largest ever online voting trial in terms of total eligible voters, and found that the way the voting website’s HTTPS connection worked opened it up to attacks that exploited flaws in the SSL protocol, including the devastating and widely discussed FREAK attack. “What we found,” Halderman said, “was a set of different vulnerabilities, each of which would have allowed a man-in-the-middle attacker to tamper with that voting application as it was being delivered.”

Teague, who warned about iVote vulnerabilities in 2012, criticized the election office for putting too much faith in an error-prone vote verification system, which consisted of a phone number that voters could call to query a backup ballot database. She said that she and other researchers had warned the commission “more than a year earlier” about flaws in the verification system’s implementation.

Unlike in Washington, D.C., Halderman and Teague were examining a live system. The New South Wales election commission hadn’t set up a mock election to let experts poke around in its system and find flaws ahead of time. By the time the two researchers discovered and reported the HTTPS vulnerabilities, Halderman said, “enough votes had been cast to change the margin of victory in the closest races that were at stake.”

“I’m not sure that there’s been an incident like that before, where security researchers were [examining an active system and] finding severe flaws like that,” said Halderman.

In a sign of mounting tension between the researchers and the government, Ian Brightwell, then the election commission’s director of information technology, brushed off the vulnerability disclosure in a defensive and technologically naive response: “We are confident … that the system is yielding the outcome that we actually initially set out to yield, and that is [because] the verification process is not telling us any faults are in the system.”

Teague scoffed at Brightwell’s response. “They’ve proudly announced that about 1.7 percent of voters successfully verified,” she wrote in an email. “But even now, more than a year after the election, there’s no public statement of the far more important statistic: of those who tried to verify, what fraction failed?”

Security researchers who followed the New South Wales drama found it telling that the government, and not Scytl, responded to Halderman and Teague’s discovery. Jefferson pointed out that because election official are legally responsible for ensuring a smooth and secure process, they have more on the line than the vendors and often feel pressured to take the lead in responding to criticisms. Scytl “just basically kept quiet about it,” Jefferson said. “They stayed under the radar. They provided a lot of material to the election officials, but the election officials were the ones who attacked the messengers—and, by the way, tried to get Vanessa Teague fired, and so on.”

Teague observed that the government’s response evinced a disappointing lack of technical expertise. “It was pretty clear the New South Wales Electoral Commission didn’t understand the seriousness of the problem,” she said. “They missed the important distinction between absence of evidence and evidence of absence. The Electoral Commission said that they didn’t see any evidence that the iVote system had been breached, which was quite correct, but they didn’t acknowledge the importance of a clear opportunity for manipulation and a total absence of evidence that the votes were right.”

These case studies provide a window into a relatively opaque area of technology, where the stakes are high for both voters and administrators—and where researchers face the wrath of committed bureaucrats for pointing out flaws in their system. But these are some of the only significant examples of internet voting platform audits that exist. That’s because, despite the hype around internet voting, it’s not widely used.

“Most countries recognize that it’s a pretty poor cost-benefit tradeoff right now,” said Halderman. “I mean, we’re facing enough threats to critical national cyber infrastructure now without taking one of our most critical government functions—determining leadership—and also putting that up as a target for potentially any other sophisticated country to try to manipulate.”

Who’s telling the truth? Vendors and researchers butt heads

Nearly every security expert interviewed for this story had harsh words for the internet voting industry, the vendors like Scytl and Smartmatic that market and sell voting technology to election administrators.

“Most companies in the voting space very closely guard the way their technology operates,” said Halderman, “to the extent that independent parties … just don’t have any opportunity to examine and check the claims that the manufacturers are making.” The result is that internet voting vendors are unusually insulated from the scrutiny that independent researchers bring to most other industries.

“It’s like the dumbest possible choices are being made by some of these companies with respect to deployed technology that should be mission-critical!”

Because opacity doesn’t come across well in public, vendors sometimes offer researchers limited access to their platforms so they can advertise themselves as being transparent. These invitations to visit company offices and read code on company laptops typically come with nondisclosure agreements that prevent researchers from publicly disclosing bugs in the code or other technical concerns.

Even worse, some of the companies that do this label their code “open source,” a descriptor that does not apply to these types of private evaluations. Open-source software can be downloaded freely by anyone at any time for independent inspection, and developers who open-source their code cannot prevent anyone from publishing the flaws they find. An audit that requires the signing of an NDA is the antithesis of the transparent, collaborative process that open-source software facilitates—a system that has produced dramatic improvements in personal security due to prompt and complete disclosures of technical vulnerabilities. “They’re really not observing an emerging best practice in this area,” McConnell said.

In an interview, Jordi Puiggali, Scytl’s senior vice president of research and security, repeatedly rejected this attitude. “It is more important to have something that is [end-to-end] verifiable [than] something that is public,” he said of demands for code transparency. “‘Public’ does not mean that it has no security issues and does not mean that it’s completely verifiable.” Later, he said, “It’s better to provide, from my point of view, verifiability instead of opening the source code.”

Yet publishing source code is at least a first step, and Scytl’s widely unpopular arguments against doing so rest on the odd justification that transparency is not a panacea—a belief held by no researcher interviewed for this story.

Jefferson said he thought he knew why vendors refused to allow researchers free access to their code: “Somewhere inside their hearts, they know perfectly well that their systems are not secure. If they really believed their own security claims, then of course they would let people test the systems all they wanted. But they don’t really believe them.”

Then there is the marketing deception. Jefferson singled out for scorn the companies’ frequent use of the term “encryption.” After telling the Daily Dot about multiple types of attacks on internet voting platforms, he noted that none of them relied on breaking encryption. “Of the top 100 ways of undermining an election, breaking the encryption is the 100th on the list of priorities. I mean, nobody would bother to try it, because there’s so many easier ways to do it. I’m willing to posit perfect encryption, and it does not weaken my argument at all.”

So why the obsession with encryption? Because, Jefferson said, it “carries power in the minds of not-so-technically-savvy policymakers and legislators and election officials.” Vendors, he said, also sprinkle other “buzzwords” into their product pitches, including “firewalls” and “redundant servers,” none of which address what he and others consider the core weaknesses of the technology. “They throw out a bunch of security-relevant words, and it sounds solid to the purchasers and fielders of these systems,” he said. “And it’s just nonsense. It’s literally nonsense.”

Internet voting vendors seem to harbor distaste for the tactics of security researchers, whose work inevitably amounts to repeated condemnations of their products. Puiggali accused researchers of trying to generate headlines and “stop an election based on” discovered vulnerabilities. “I respect what they do, and I think that the fact of finding security problems is good,” he said. “But maybe I disagree on the way that they transmit this information.”

Puiggali seemed to believe that some researchers’ associations with voting advocacy groups had biased their work. When the Daily Dot asked why the public should trust researchers working for a vendor over independent academics, he countered in part by saying, “I don’t know if, maybe, you can call them ‘independent’ or not, since most of these experts … belong to one organization, the same organization.”

This appeared to be a reference to the Verified Voting Foundation, which has published many papers pointing out flaws in internet voting systems, including Halderman and Teague’s famous takedown of the New South Wales system. Puiggali dismissed the findings in that audit by claiming that, for the discovered vulnerability to matter, attackers would have to exploit three separate problems, including using social engineering to fool the phone verification process. (He did acknowledge that social engineering is often trivially easy, somewhat undermining his claim about the difficulty of exploiting the flaw.)

Puiggali also leveled a broader complaint that seems typical of how many people at internet voting vendors see headline-grabbing security audits. “The fact that [there] is a problem,” he said, “does not mean that we need to stop something.” Instead, he said, the researchers should simply notify the company so it can perform an internal assessment of the risk factor. “We need to evaluate how easy it is to solve it and how fast it is to solve it, and then, based on this, you can decide.”

After talking to Puiggali, it became clear why technical experts who are convinced of internet voting’s liabilities have grown exasperated by what they hear from Scytl and other vendors. “There are experts [who] consider that this is not secure, but there are other experts that are working for making this secure,” he said, defending his company’s work. “It’s like saying, ‘There are people that prefer to eat meat, others vegetables.’ I respect their opinion.”

Halderman was pessimistic when asked whether he could foresee a thaw in relations between vendors and experts that would lead to more fulsome code reviews. “I have working relationships with certain computer scientists who work at some of these companies,” he said, “and basically the signs that I have gotten from them are that there is no way this would be permitted.”

Why, given the problems with the technology and the secrecy of the vendors, do election administrators still buy these products? Because they feel like they have no choice. “At its core,” said Kiniry, “the reaction from elections officials has been one of, ‘Well, I don’t really have any other choice. I understand that it’s hackable by people like you, but at the moment, I don’t have any other choice. So I’m going to keep doing it.’”

During a Skype video interview with the Daily Dot, Kiniry read a quote from an election official that he said illustrated the situation. “Young people today are doing most everything else using their phone,” the woman wrote, “so to engage them, I feel that we need to be seriously considering what it would take to make this initiative possible.”

“The desire to make voting more convenient,” said Dill, “is so great that [officials] just sort of set aside the security concerns and say, ‘Well, some smart person will solve those,’ or, ‘It can’t be that bad,’ or something like that.”

These political and corporate motivations combine to produce what Dill repeatedly describe as a “game of whack-a-mole.”

“People think that internet voting must be a great idea, because they do other kinds of actions over the internet,” he said. “People submit legislation on this … with no consultation from technical people. And in some cases, they hear the opinions of technical people, but they ignore them. I’ve been involved with some of these discussions, and it’s like we’re talking totally across purposes. So [we] explain all the security difficulties with internet voting, and what comes back is, ‘Yes, but we have to increase voter participation and we have to increase access to the ballot.’”

Local internet voting projects are hard to derail for one simple reason: They sound good, and no politician will back down from a plan that sounds good just because academics raise theoretical concerns. Security experts can describe cryptographic weaknesses at legislative hearings until they’re blue in the face, but as Dill explained, “once somebody puts their name behind an idea, even a dumb idea, they’re invested in it, and it’s hard to get them to change.”

No breakthrough in sight

If the past is any indication, election technology improvements will occur slowly and unevenly. “If you look at something like the [2005] Real ID Act, which is the act to improve driver’s licenses,” said University of Utah political science professor Thad Hall, “there are still states that have not complied with that [and] still controversies around something as basic as … what should be the security features in your driver’s license.”

Security experts’ top recommendation for advancing election technology was to increase funding for cybersecurity research. “We need to get better at security generally before we’re going to able to solve the online voting problem,” Halderman said. “It’s going to take some fundamental advances in the way we do things like authentication online, like keeping intruders out of servers and malware off of people’s computers. There are these enormous problems that we need to tackle first.”

“People think that internet voting must be a great idea, because they do other kinds of actions over the internet.”

For technology to make elections better, voters would also have to feel comfortable that the process was strictly regulated. McConnell recommended that Congress ask a regulatory agency, such as the Election Assistance Commission, to launch an inquiry into internet voting. Just as regulations on food, water, air, and kitchen appliances give citizens confidence in the things they put in their bodies and homes, regulations on internet voting would ensure that the industry behaves responsibly.

Neither the Department of Homeland Security nor the Election Assistance Commission answered requests for comment about their views of internet voting’s security issues.

Perhaps we’ll accept that some things are just too risky and scale back our ambitions. Kiniry and Zimmerman wrote a report about PDF ballot tampering that has led to what Kiniry called “constructive work” on a more modest internet voting approach: downloading blank ballots, filling them out either electronically or after printing them out, and then mailing them in. It’s essentially a slightly easier version of current vote-by-mail programs, but even a slightly easier system might draw in more people.

“What we ought to be doing,” Halderman said, is “combining the best of paper with the best of electronic records. … Giving up the security advantages of paper … just for the convenience of voting electronically seems profoundly misguided.”

For now, the bottom line is that very smart people have been working very hard for decades to crack the code of secure internet voting, and they say it’s not ready for primetime.

“There are many dozens of researchers who are at the forefront of their field in areas of cryptography and computer security who have been trying for many years to build fundamentally secure cryptographic voting systems but do not feel that the technology has gotten to nearly a level where it’s safe to deploy and practice,” Halderman said. “Hopefully, we will be able to solve this problem, but it seems to me, anyway, and to many of my colleagues, that we’re a decade or more away from being able to say [that] this is something we know how to do.”