Some moments that change the course of history are obvious instantly.

The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The 2003 invasion of Iraq. Broadcast live around the globe, the gruesome images of these events set the stage for the 21st century. Everyone knew it even while the cameras were rolling.

Others you have likely never heard of.

On a chilly Baltic spring day in 2007, a much quieter act of violence began with just an error message here, a disconnected server there. It would end by crippling the institutions of a major European capital, escalating what had been a war of words between two countries, Russia and Estonia, into something unprecedented: Cyberwar.

This surreptitious smash into Estonia’s digital heart sparked a shift in the fighting stance of the world’s most powerful militaries, richest governments, and most cutting-edge private companies that continues to this day.

Estonians compare the day to their own 9/11. Imagine what would happen if Wall St. financial institutions and every American bank was crushed under the weight of a cyberattack while Washington, D.C.’s institutions fell apart under the same withering offensive. Meanwhile, what if no one could read newspapers or call 911?

That’s the level of attack that Estonia faced.

In July 2016, the world’s most powerful military alliance will meet in Poland. Over the last decade, NATO’s priorities have changed. In the wake of the fall of the Soviet Union, an attack by Russia—of any kind—once seemed almost inconceivable.

But military tension has returned to Eastern Europe as Russia and NATO eye each other warily. The Western alliance was shifting, its centers of power moving steadily eastward to capitals like Warsaw, Ankara, and Tallinn. Two old rivals are standing up.

The pressure has been building since that historic moment in 2007.

It’s been called Web War I. That’s how new and monumental this incident was for those who experienced it. It set the stage for Web Wars to come. And it all started with a statue.

Soviet ‘liberators’

As with so many historic singular moments, the lead up to Web War I is marked by decades of blood and oppression.

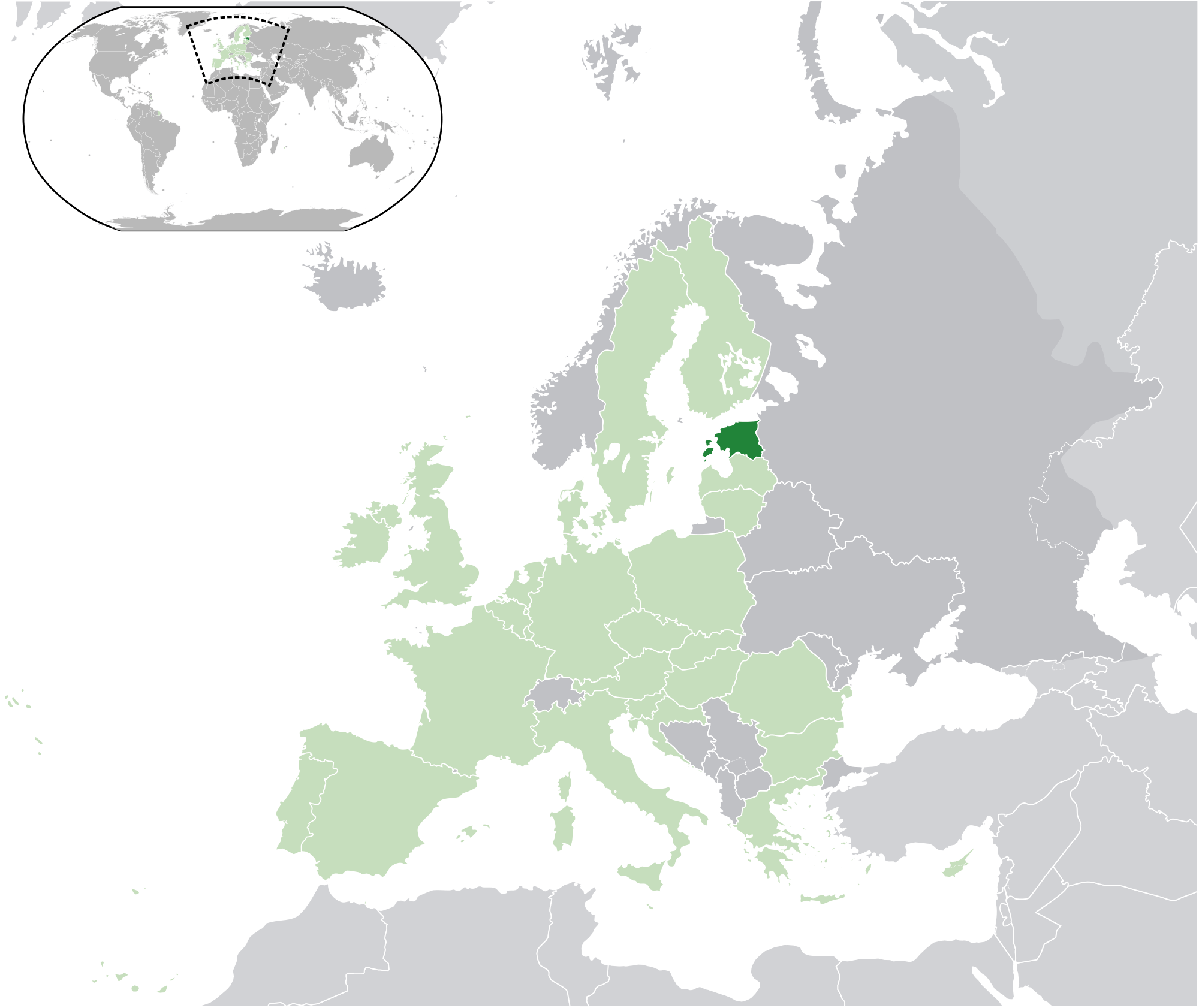

Estonia is a small country in Northern Europe. It borders the Baltic Sea, Latvia, and Russia. That last one is big in every sense of the word.

A former Soviet satellite, Estonia was on the wrong end of a half-century occupation that turned the country into a hyper-militarized border zone from which the Soviet Army poised its war-fighting power toward the West.

In the middle of the 20th century, the country was traded back and forth between the Soviets and Nazis in bloodshed that resulted not just in tens of thousands of Estonian deaths but also a brutal authoritarian disruption to their society that ultimately lasted for decades. Before that, Estonia was ruled for centuries by powers like Sweden and Denmark.

True independence was a foreign concept to many Estonians, but the 20th century brought a “national awakening” in which millions yearned for sovereignty.

When the Soviets and Nazis divided up Eastern Europe preceding World War II, Estonia went to the Russians, who promptly occupied the country and installed a puppet government. The Nazis invaded and occupied from 1941 to 1944, when the Soviets returned for what seemed would be forever.

Estonia’s Russian overlords didn’t see their occupation as brutal or disruptive or illegal the way the West did. The Soviet propagandists—and today’s Russian government—very earnestly said it was all legitimate.

In 1947, with Eastern European rubble still soaked in the horrors of war, the Soviets built a six-foot-tall bronze statue memorializing their soldiers and war effort. They put it right in downtown Tallinn, Estonia’s coastal capital. The Soviets called it Monument to the Liberators of Tallinn.

From whom, exactly, did the Soviets liberate Tallinn?

With the specter of the Red Army looming, the Nazis withdrew from that city without fighting. It was the Estonians who re-established an independent country on Sept. 18, 1944. By Sept. 22, the Soviets took hold of the city again. In that way, the Russians “liberated” Talinn from the Estonians themselves.

As a result, the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn is seen by many Estonians as a symbol of Soviet occupation. After the fall of the Soviet Union, a growing number of Estonians wanted it gone. More hard-line activists pushed to have the thing outright destroyed.

In 2007, the Estonian government was getting ready to finally move the Bronze Soldier. In response, ethnic Russians in the country rioted in the worst unrest Estonia had seen since the brief but bloody war of independence that commenced when the Soviets occupied the country in 1944.

In two nights of rioting, one man was killed, 153 people were injured, and 800 arrests were made in the capital. Protesters chanted “Russia” and waved Russian flags. They threw molotov cocktails, looted, and let their dissatisfaction be known through the international language of arbitrary destruction.

The unrest became known as the Bronze Night.

Ethnic Russians felt the removal of the statue was one act of discrimination among many, just another kick in the gut in a war against their equal rights in Estonia.

The Russian government, just over the Estonia’s eastern border, warned the small country that removing the statue would be “disastrous for Estonians.”

After the first night of rioting, on April 27, the Estonian government dismantled the Bronze Soldier and moved it from its original location.

Web War I

That’s when the crucial and historic moment began.

As the petrol bombs flew on the streets, a wave of digital violence hit Estonia that caught the country completely off-guard.

Estonia is Europe’s most connected country. They’ve pioneered e-government and Internet voting. They’re a world leader in Internet freedom. To say the country is “wired” would be a misnomer—it’s Wi-Fi that saturates the air these days, so they’re thoroughly wireless.

The nation relies more on Skype, which was created in the country in 2003, than old-fashioned phone systems. A whopping 98 percent of the country’s bank transactions are done online. They rely so heavily on the Internet, and they did it earlier than any perhaps other country in the world.

That’s why it was such a shock to their system when, with unprecedented speed, the website of Estonia’s largest newspaper was brought to its knees, convulsing, crashing, and ultimately collapsing under the weight of a wave of Internet traffic it couldn’t support.

The techies at the Postimees, Estonia’s leading newspaper, told Joshua Davis at Wired what happened that day:

The future was looking perilous. Ago Väärsi, head of IT at the Posttimes newspaper, watched as automated computer programs continued to spew posts onto the commentary pages of the Postimees Web site, creating a two-fold problem: The spam overloaded the server’s processors and hogged bandwidth. Väärsi turned off the comments feature. That saved bandwidth — the meter showed that there was still capacity — but what did get through tied the machines into knots and crashed them repeatedly. He discovered that the attackers were constantly tweaking their malicious server requests to evade the filters. Whoever was behind this was sophisticated, fast, and intelligent.

A few days later, it happened again.

Internet traffic from around the world flooded into Estonian networks and overwhelmed them. The Posttimes website crashed, as did other Estonian publications. The only option Väärsi saw was to block all international traffic. That fended off the attacks and brought the site up. But it also meant no one from outside Estonia could reach the Posttimes. They had had to go silent to beat the attackers. For journalists, that means they got beat.

That was the start.

The tsunami of traffic was a botnet—numerous botnets, really—a horde of computers numbering in the hundreds of thousands, enslaved by hackers to act as a weapon for a botnet master. In enough quantity, bandwidth is a hard, blunt object that threatens to knock networks down.

Over the course of several days, the botnets hit banks, broadcasters, police, and the national government. The parliament and ministries networks were overwhelmed, government communication networks were knocked down. The national emergency number buckled. The country’s Internet infrastructure was being hit hard with unrelenting traffic that was orders of magnitudes larger than what Estonian networks were capable of handling.

The immediate defense was, again, to cut Estonian networks off from the outside world, block all international traffic, and then regroup. But if you’re effectively cut off from the outside world, getting outside help is a challenge.

A stroke of luck hit when Estonian authorities learned that they just happened to have Internet royalty in their capital during this attack. In town was Kurtis Lindqvist, CEO of the Swedish independent Internet infrastructure organization called Netnod. Netnod runs i.root-servers.net, one of 13 DNS root-name servers in the world, which manages worldwide Internet traffic.

After four days under attack, it took face-to-face meetings between Lindqvist and Estonia’s top cybersecurity authorities to begin to persuade the world’s Internet service providers to single out and blacklist the attackers.

The Russian government denied involvement in the attacks as Estonia’s foreign minister directly accused President Vladimir Putin’s government of being behind the offensive.

Incensed, Estonian Foreign minister Urmas Paet said, “The European Union is under attack, because Russia is attacking Estonia. The attacks are virtual, psychological, and real.”

Moscow proclaimed its innocence but remained hostile in its rhetoric.

As troops marched for Russia’s celebration of Victory Day, commemorating their triumph over Nazi Germany, Putin told troops marching in Red Square, “Those who are trying today to … desecrate memorials to war heroes are insulting their own people, sowing discord and new distrust between states and people.”

Russia also implemented limited sanctions against Estonia during this period, suspending some trains carrying passengers and raw materials to Tallinn.

In Estonia, the message was received loud and clear: You’re not as safe as you think you are. But a question remained: Could anyone prove who was sending the message?

Origins of the attack

Pinpointing and crediting a state-level cyberattack is a difficult task that can easily rise to near impossible.

But here there are some crucial clues. Wired, working with the security firm Arbor Networks, identified overlap between the botnet attacking Estonia and botnets that were previously used to attack Russian opposition politicians like Garry Kasparov.

Russian-language forums were full of messages urging an attack and enlisting foot soldiers in the lead-up to the offensive.

Then, two weeks after the digital blitzkreig began, it stopped without warning. The botnets ceased their offensive and the weight on Estonian networks lifted. Pressure had been exerted.

Russians are the chief suspects, but proof positive is another question. And whether this was direct government action or private hackers or a potent combination of the two, that’s a more difficult question. A single ethnic Russian living in Estonia was charged, admitted his guilt in taking part, and was convicted in 2008.

This whole affair might sound familiar: Ethnic Russians in a country bordering the motherland, a country previously occupied by Soviets, Moscow’s shadowy but forceful reach into a smaller neighbor on the basis of helping those ethnic Russians.

If it sounds like a dress rehearsal for 2014’s war in Ukraine, you’re not alone.

Web War I was one of the first steps taken into a modern Europe where tensions between Russia and her neighbors are rising, military budgets are growing, and hard American power is seen now in tanks on the ground across Eastern Europe and a cyberwar stance with eyes directly on Moscow.

Estonia is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the world’s most powerful military alliance, and, from a Russian perspective, one of the world’s most aggressive villains. Not coincidentally, the expansion of NATO and Ukraine’s potential membership was one of the matches that set the country aflame in 2014.

Ene Ergma, who was speaker of the Estonian parliament during the 2007 attacks, said, “Attacking us is one way of checking NATO’s defenses. They could examine the alliance’s readiness under the cover of the statue protest.”

In the wake of these attacks, Estonia compared them to terrorist action and urged a strong NATO response. The alliance wasn’t ready: There had never been a cyberattack like this; there was no playbook to study. They were unprepared on a technological and strategic level. As such, this moment also started fundamental debates that are still being sorted out.

Should a massive attack like this be treated as an act of war? It’s a question that is still being sorted out. NATO networks were under attack from the same botnets that hit Estonia, and they were defended by a five-year-old program that, after Estonia, was expanded beyond NATO networks. A year later, NATO established its cyberdefense center in Estonia’s capital.

In 2016, it’s easy to forget how new a cyberattack of this scale was for the world’s great powers. Only one attack, called Titan Rain, was larger than the bombardment of Estonia. It endured from around 2003 to around 2006 and targeted American networks. The British and Russians may have been in the crosshairs as well. China got the blame, as it so often does, but proof remains illusive.

A decade later, we still don’t know what was stolen in Titan Rain and even who entirely was hit.

The attack on Estonia, however, was loud and clear. The scale and sophistication of the attack was unprecedented. It’s set the tone for Eastern Europe, and the world, ever since, as cyberwar capabilities have increasingly come into focus. When you hear of the worst-case scenarios when it comes to the future of cyberwar, experts are imagining Estonia first when they imagine the future.

Estonian authorities’ comparison of Web War I to 9/11 is tricky, obviously, but it has real merit. America’s course in the world shifted as a result of 9/11. What the U.S. did with its military, how American power interacted with the world—it all changed.

Web War I changed all this with Estonia, too, and it had broader effects that continue to ripple through NATO to Russia and to the rest of the world today.

Estonia in 2007 is when the threat began to grow in the minds of the world’s great powers. When a country’s banks cannot freely move money, that’s when you’ve hit a nerve.

Now NATO is shifting. In Western Europe, military budgets are mostly shrinking. The three European titans—France, Germany, the United Kingdom—are not looking like they’ll play the same role in the alliance moving forward. But in the East, there’s a new combativeness that is in large part responding to Russia’s resurgence.

Little Estonia—tiny but wealthy and long on the cutting edge of technology—has become a cornerstone of the West’s cyberwar capabilities. Poland is building up its military, and Turkey is spending more on fighting capabilities and NATO itself.

Web War I changed the face of NATO, it changed the minds of European powers, and it changed the fighting stance of a world that was caught totally off guard by these attacks.

When they write the history books on the 21st century, expect special attention to be paid to the day in Tallinn where moltov cocktails flew and networks crashed.