I was shocked by how much fun I had with Far Cry Primal, because the idea of setting a Far Cry game in 10,000 B.C. sounds absurd.

The Far Cry series, since its inception in 2004, has been about toting arsenals of firearms and explosives around huge, open worlds while taking down the private armies of mercenaries, maniacs, and warlords by brute force, stealth, or clever tricks.

Far Cry Primal, on the other hand, is about carrying stone-tipped spears and slingshots through a Mesolithic forest, riding on the backs of bears and sabertooth tigers you’ve tamed like something out of The Beastmaster, and fighting tribes of cannibals and cavemen using similar tactics.

Even with a change of environment this dramatic, Far Cry Primal fits right in with the rest of the series. Some elements of the Far Cry formula actually make more sense in Far Cry Primal than they did in previous Far Cry games, and there’s something brutal and honest about translating a first-person shooter into an experience of such naked aggression.

I still can’t get over the degree to which Far Cry Primal feels like a complete success, because I was ready to dismiss the game’s seemingly bizarre concept out of hand.

In Far Cry Primal you play as Takkar, who belongs to a tribe of people called the Wenja. You have tracked the scattered remnants of your tribe to a lush forest land in Central Asia named Oros, and your main task is to gather and strengthen them against other tribes that want to wipe out the Wenja.

All the dialogue in Far Cry Primal is subtitled, because it’s spoken in a tongue created by linguists to sound proto-European. (I’m sure Ubisoft Montreal could have found some way to get around this and have the characters speak in modern languages. I’m also sure critics would have ripped harshly into the game had Ubisoft Montreal chosen to do so.)

Even if the developer’s hand was forced on this question, I still think the degree to which Far Cry Primal commits to this choice is admirable.

The other tribes in the game, the Udam and the Izila, gather around bonfires and in large village-like outposts spread across Oros. By killing everyone at these locations you seize them for the Wenja and create fast-travel locations around the sizable map. There are caves to explore for collectibles, small campfires at which to find resource stashes, a bevy of different plants you can gather, and different animals you can hunt to obtain crafting resources.

These design rudiments of Far Cry Primal will be instantly recognizable to long-time Far Cry players. Far Cry Primal’s map in particular almost feels like a re-skin of the map from Far Cry 4.

The metagame is partly where Far Cry Primal carves its own identity into the series. Takkar’s primary objective is to gather the Wenja together into a single village. The supporting characters among the Wenja are specialists that teach Takkar unique sets of skills. The gathering expert unlocks the ability to earn more resources when you harvest plants, and the hunting expert increases the damage you do to animals, for example.

Takkar has to build huts for these specialists as they move into the village. Improving these huts unlocks new skills and new missions. There are population prerequisites for all of these improvements, so recruiting new Wenja is a constant concern.

Whenever Takkar clears out an enemy bonfire or outpost, the Wenja population increases. Chasing predators away from Wenja hunting grounds and rescuing tribespeople from capture, among other things, also add tribe members to the village. It’s important to prevent any Wenja from being killed in addition to completing these side activities. Every casualty is one less person to move into the village when the mission is complete.

Changing the context and consequences of these side missions and random activities made them feel less like side content and more like priority tasks. I appreciated having a reason to engage with all of this content beyond doing it for its own sake.

Resource-gathering is more integral to Far Cry Primal than previous Far Cry games. It also makes more sense. In Far Cry 4, for example, you skinned animals to make new ammo belts or loot bags and the like. You used plants to make medicinal products.

It was silly that Far Cry 4’s hero, Ajay, an inexperienced kid from the United States, got transported to a Himalayan country and in short order turned into a commando right at home in the ranks of Delta Force. Demonstrated by his sudden ability to gather animal skins and herbal supplements and live off the land, it seemed he had watched too many episodes of Survivorman.

Takkar, on the other hand, is part of a tribe of hunter-gatherers. Stopping to snap off Alder wood branches, collecting flint and shale, and finding plants for herbal medicines is precisely what he ought to be doing. This harmony between the tasks and the game’s environment made resource-gathering blend more smoothly into the game, making it feel less like a chore.

Resource-gathering is important for building expansions to your village and, more immediately, for crafting weapons and ammo. You never run out of bullets in Far Cry Primal. You do run out of hardwood for arrows. Hardwood is liberally spread around the map—it shouldn’t take you more than a few seconds to find some at any time—so ammunition is still practically limitless. That means no constant stops to a trading outpost or town to re-up your ammo.

There’s also no money in Far Cry Primal. There are crafting materials, but there’s no loot. This eliminates the need to pore through inventories and decide which items to sell or which items to keep. You can spend significant amounts of time exploring in Far Cry Primal without having to check in at base, which is perfect for an open-world game.

In Far Cry 4 you could ride an elephant and use it like a battering ram, and in dream-like sequences a tiger would follow the player’s attack commands. Far Cry Primal expands these concepts into a Beastmaster-esque animal taming system that feels like hunting collectibles while also expanding your arsenal of weapons.

Takkar can summon an owl, see through its eyes, and control its flight. The owl can spot and tag animals and enemies, drop weapons like fire bombs, and make diving attacks with its claws. It can also mark waypoints on the map, which makes the owl an effective scout.

Takkar can unlock the ability to tame wolves, bears, badgers, and a variety of big cats including sabertooth tigers. They each have strength, speed, and stealth modifiers, so you can select a beast that matches your play style. When Takkar is accompanied by one of his beasts, he can mark targets for them to attack, and they’ll defend him automatically. There are 17 animals Takkar can add to his beast arsenal.

Hunter-vision allows Takar to clearly see animals he can hunt or tame by muting the colors in the environment and highlighting the animals in yellow. If he spears an animal but doesn’t kill it outright, Takkar can follow the blood trail using hunter vision and track the animal down. Hunter-vision can also be upgraded to highlight plants and other resources.

Mammoths, brown bears, and two breeds of giant cat can be mounted and ridden. Riding into an Udam stronghold atop a giant bear, jumping off, and setting him loose never became ceased to be funny after the first time I tried it.

Far Cry Primal was generally funny to me in a way I don’t think the developers intended. There was something outrageous about the raw aggression of picking up a stone club and bashing in a caveman’s head. After about an hour, killing people with stone clubs stopped feeling strange, and that’s when Far Cry Primal got me thinking about the nature of first-person shooters in general.

I adore first-person shooters (FPS) more than any other genre. I also recognize the meatheadedness at their core. In an FPS game, you run around and kill shit. There may be puzzles thrown into the formula, or RPG-style skill trees and character builds to play with, required acrobatic feats, or even a reasonably good story, but when all’s said and done FPS games are about throwing rounds and shooting people, hopefully in the head.

So why should shooting stone-tipped arrows into the skulls of caveman, attacking them with sabertooth tigers, or having owls execute them with razor-sharp talons in divebomb attacks be any different? Why should any of this feel ridiculous?

Yes, Takkar’s hunter-vision is entirely fantastical and maybe even silly, but is it any different than a super-soldier with cybernetic enhancements that allow him to see through buildings down the length of an entire city block? Few people bat an eye at combat exoskeletons, walking tanks, or miniature recon drones, either, in first-person shooters.

I did wish that Ubisoft Montreal could have found a way to replace minimaps and waypoints with some other type of navigational aids that would have felt less dissonant with Far Cry Primal’s Stone Age theme. Then again, minimaps and waypoints make little sense in any shooter, regardless of the time period, unless your character is equipped for a holographic heads-up display.

It may sound trite, but there actually was something primal about Far Cry Primal in terms of how it handled genre identity. It dispenses with any notions of gritty realism, noir storytelling, or military heroism, and boils things down to brutal violence and plain-old silliness. I found this refreshing.

That sense of refreshment coupled with the unique setting made Far Cry Primal an enjoyable open-world shooter that ought to appeal to genre fans beyond the established Far Cry audience.

Disclosure: Our Xbox One review copy of Far Cry Primal was provided courtesy of Ubisoft.

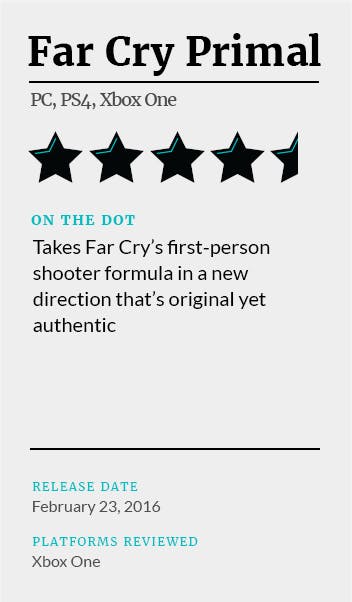

Illustration via Ubisoft