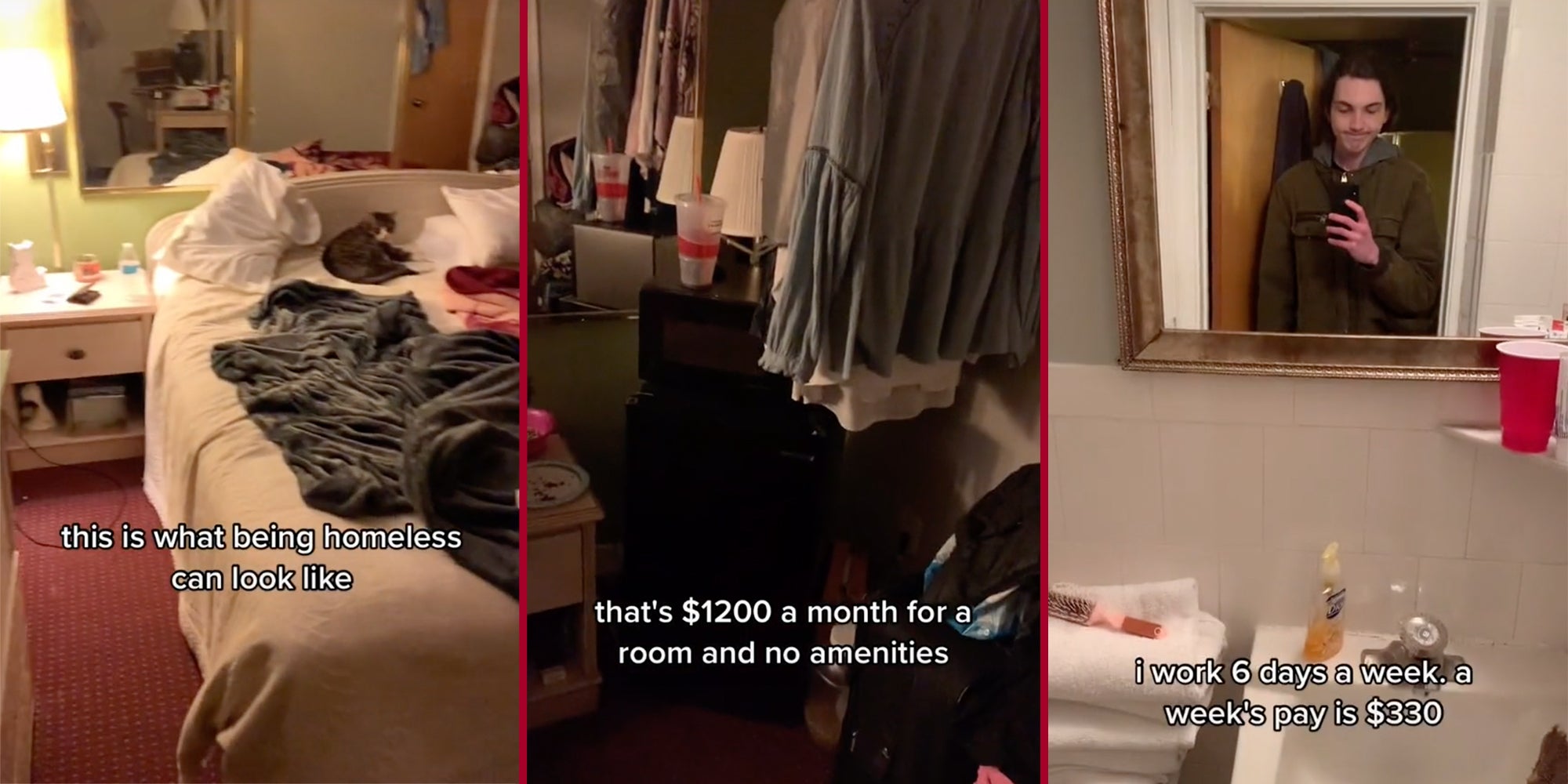

Julian DiAngelo was mentally exhausted last fall. He had lived with friends for months while exploring housing options that turned out to be dead ends. In November, he finally joined his mother, who also didn’t have a home at the time, in a roadside hotel in Millersville, Maryland. DiAngelo worked as a food runner and busser at a restaurant while occasionally helping his mother make DoorDash deliveries.

On a particularly cold night in the hotel, DiAngelo was lying in bed, frustrated with his lack of permanent housing and that so many other people he interacted with on a daily basis were in the same, difficult position.

“I’m like, ‘This is like this is not OK,’” DiAngelo told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. “It was absolutely fucked. And it wasn’t just me living there; it was me, my mom, and my neighbors living there. Across the way, there was another roadside motel. It was owned by the same people. That place was filled up, you could see the same cars [there every day].”

DiAngelo decided to post a TikTok about where he was staying. In the video, he walks through the room he shares with his mother and shows their living conditions. He explains how he sometimes can’t afford to eat, has to walk 10 minutes on the side of a highway to get to a gas station—the closest nearby store—and that his weekly pay is only $30 more than what he pays per week at the motel.

“Self sustainability is impossible in these conditions,” DiAngelo wrote in the video’s overlay text. “I and so many other people are stuck living like this just to stay warm. The only reason I can afford to eat is because I get a shift meal at work.”

The 21-year-old’s video went viral, or as he likes to say, he got “lucky” with TikTok’s algorithm. His TikTok has been viewed over a million times and received almost 5,000 comments. Some people commented that DiAngelo should join the Army; others doubted his story and told him he should work more or move. A few identified with his situation and acknowledged just how costly being without a home really is. (At the time of publication, DiAngelo was living in an apartment with his brother.)

“Being poor is extremely expensive,” TikTok user @inclusivechicken commented on DiAngelo’s video. “People [who] have not experienced it have no idea.”

The costs of poverty are cyclical. Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, writes for the Atlantic that jobs belonging to many below the poverty line “pay so little that you cannot accumulate even a couple of hundred dollars to help you make the transition to a better-paying job.”

Ehrenreich also explains barriers to housing including the first month’s rent and a security deposit can make people turn to an “overpriced residential motel,” like the one DiAngelo lived in. Without a kitchen, overpriced convenience store food becomes one of the only options. That’s only covering food and shelter, the absolute bare necessities.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness reported that more than half a million Americans were homeless in 2020. On a typical night in 2021, over 326,000 people experienced “sheltered homelessness,” which means they stayed in a shelter or another type of transitional housing, like a hotel, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The word “unhoused” has become a popular, and at times preferable, alternative to “homeless” because of the negative connotations associated with the latter. As explained by Unhoused.org, a startup working to end homelessness, unhoused “implies that there is a moral and social assumption that everyone should be housed in the first place.” (The Daily Dot uses both terms in this article to reflect the descriptions used by sources.)

Regardless of how it’s described, and despite how common homelessness is, the experience isn’t one that people in the U.S. get widespread and varied exposure to in media.

DiAngelo is one of dozens of unhoused people who post about their financial survival tactics and daily lives on TikTok. Doing so has its benefits: TikTokers without homes can tell their own stories and potentially field donations from sympathetic viewers. On a wider scale, unhoused TikTokers are rapidly transforming the public perception of what modern-day homelessness looks like, thanks to TikTok’s algorithm that grants them hundreds of thousands—or even millions—of views.

TikTok, which has been heralded as the world’s “fastest-growing social network” with over a billion users, has an algorithm that is trained by each user, according to a Wall Street Journal investigation.

“The algorithm on TikTok can get much more powerful and it can be able to learn your vulnerabilities much faster,” Guillaume Chaslot, the founder of AlgoTransparency.org told the Journal. “The algorithm is able to find the piece of content that you are vulnerable to, that will make you click, that will make you watch.”

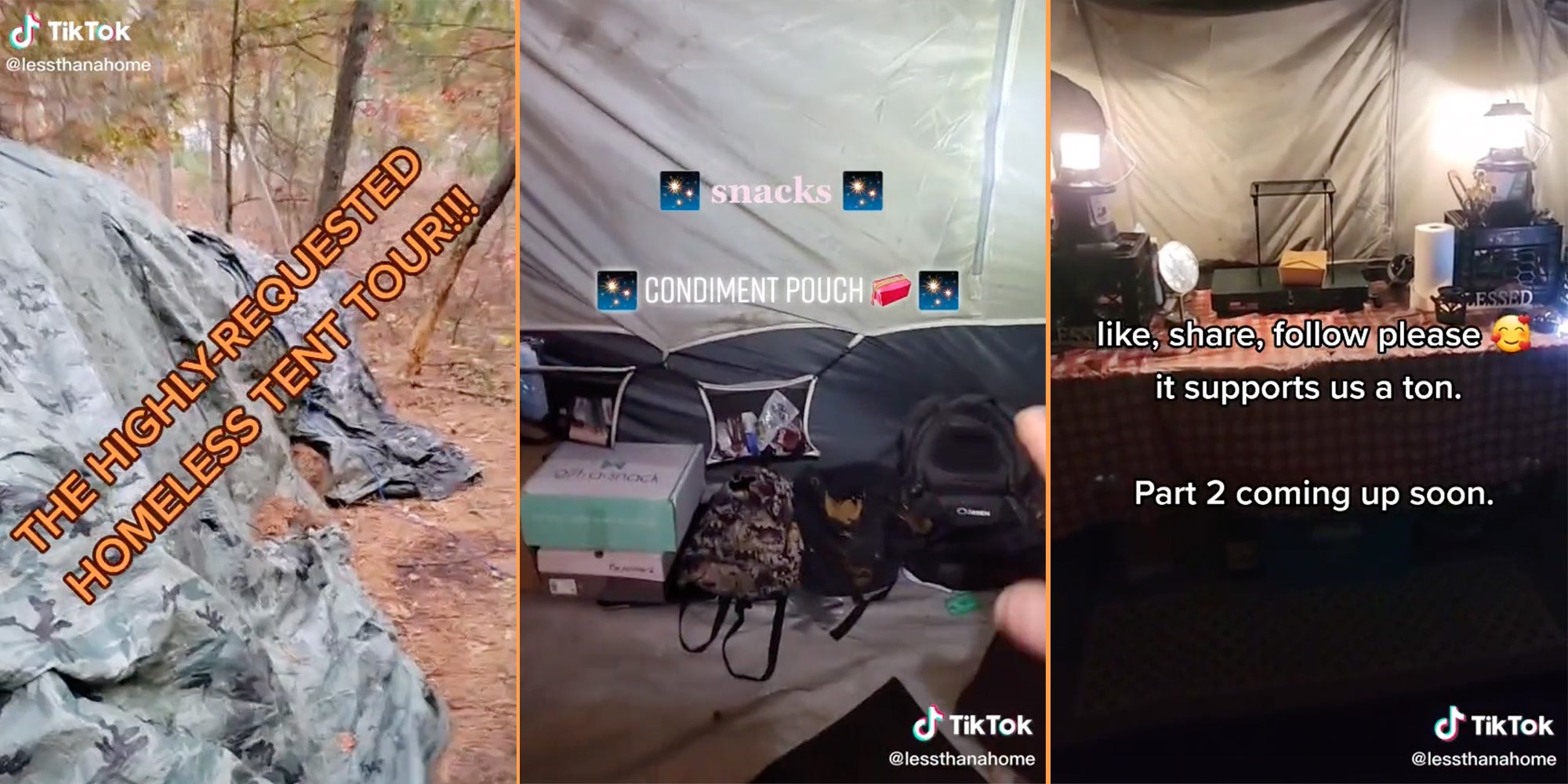

The algorithm’s power results in massive view counts for videos from unhoused people. @LessThanAHome, a TikTok account run by new parents Phoenix and Raven, shares “homeless pro tips” for unhoused viewers who are in need of a “guide on surviving homelessness,” Phoenix told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. Most of their videos showing the pair living in a tent in Massachusetts’ woods accumulated at least 50,000 views, including a tent tour that received almost 260,000. (At the time of publication, Phoenix, Raven, and their new baby had secured housing in Rhode Island.)

Kyla Kelly, who lives in Florida with her husband and dog in their car, shares videos of her life as a “working-class homeless” person, Kelly told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. Two of her most popular videos—one showing her and her husband’s storage unit, and one showing their setup to sleep in the back of their 2005 Honda Pilot in a parking lot—have 4.4 and 4.5 million views, respectively.

The Journal’s investigation into the algorithm also revealed that TikTok includes “disruptive content” to “help the user discover different content” from what they usually watch. While there are certainly users who are interested in content about homelessness and/or from unhoused people, it’s also quintessential disruptive content. Videos from the TikTokers who spoke with the Daily Dot get high engagement, which helps land them on the coveted For You Page.

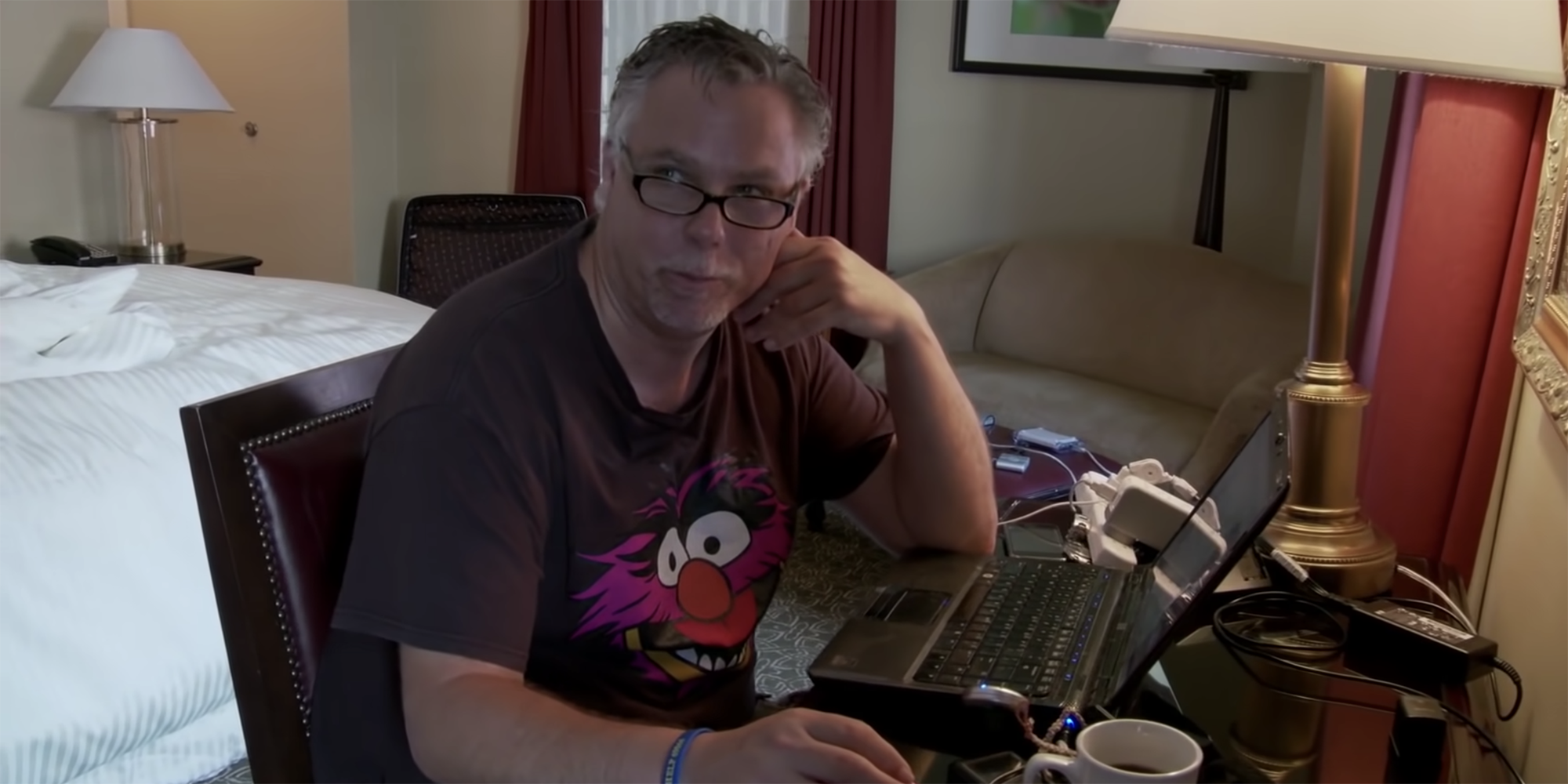

Unhoused TikTokers don’t necessarily post about their experiences to go viral. They do so because it’s personally beneficial; it feels good to tell your story when you have been struggling in silence. Mark Horvath, the founder of Invisible People, a nonprofit that produces daily journalism by and about homeless and formerly homeless people, says that sharing their situation widely can help them connect with people who can help them.

DiAngelo, Kelly, and Courtney Dorritie, another unhoused TikToker based in New York City, told the Daily Dot that people who became aware of their housing and financial situations on TikTok sent them donations and/or care packages.

In a phone interview with the Daily Dot, Horvath explained that “the No. 1 way people get their information—or their paradigms—on homelessness is what they see with their own eyes.”

“People are seeing growing homelessness,” Horvath told the Daily Dot. “And because of COVID and because of the pandemic, visible homelessness has grown. And people have become more frightened by it.”

Creators like DiAngelo, Kelly, Dorritie, and Phoenix from @LessThanAHome are introducing people to the reality of being unhoused from their perspective, using their own words.

“We had started producing content to kind of like give a peek behind the curtain,” Phoenix told the Daily Dot. The TikToker shared that another one of his motivations to make videos was combatting his own shame about being unhoused. He wanted to show that although he and his partner had dealt with substance abuse issues in the past, their addictions had nothing to do with them being homeless.

Dorritie, who at the time of publishing lived in a long-term shelter in New York City and was awaiting approval for a housing voucher by the city, felt similarly. She said when she first got sober, she “felt kind of bad” that her life didn’t “immediately turn around.”

“So I was just posting the whole journey to show people that it takes a while,” she told the Daily Dot. “And [getting one’s life back on track is] not like an immediate thing. It does happen, eventually.”

Kelly said she wanted people to know her story because before she was living in her car, she would ignore unhoused folks and had a “sucks for them” mentality.

“God, I was such an asshole. But when it happens to you, you’re like, ‘Oh, wow, I actually get it now,’” she recalled in a phone interview with the Daily Dot. “I wanted to make a TikTok page to shed light on the modern-day homeless.”

All of the unhoused creators are forming nuanced and realistic media representations of what being unhoused looks like and means while putting faces to the rising numbers associated with homelessness. In 2020, for the fourth year in a row, homelessness increased, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report.

Media Studies Professor Clemencia Rodríguez at Temple University says that in addition to what we see in real life, the public’s perception of groups of people is also heavily impacted by the entertainment media.

“Many more people engage with audio-visual entertainment media than with, you know, journalism,” Rodríguez told the Daily Dot in a phone interview. “If we did an analysis of representations of people living without a home in [mainstream entertainment media], that’s where we would start finding this very homogenous view of [unhoused people].”

Horvath, who founded Invisible People in 2009 when he was homeless himself, still posts unedited YouTube videos of unhoused people sharing their life stories. His theory on why the content he posts gets so many views—his most recent video has been watched more than 14,000 times; one of the channel’s videos from nine years ago has over 14 million views—is that people are innately curious about unhoused people, and they’re able to consume content about them in a “safe space” of their choosing rather than talking to an unhoused person on the street.

“[Someone] might not have the emotional energy to extend empathy to [an unhoused person], you might not feel safe,” Horvath told the Daily Dot. Videos are able to explain the experiences of unhoused people for viewers who are usually watching in a relaxed emotional state wherein they can extend empathy—and possibly shift their perspective on homelessness.

While a change in public perception isn’t an exact science, Horvath says that he has seen more positive, realistic media coverage about unhoused people lately. Phoenix says that he’s seen an increase in unhoused people sharing their stories and lives on TikTok.

“When you’re experiencing homelessness, the biggest thing that you want is just like human connection. You just want a friend, someone to listen, someone to talk to,” Phoenix said. “I think that if more people were sharing their stories, I think that it would help fight those stigmas and stereotypes.”

Must-reads on the Daily Dot

| An autistic TikToker reported an ableist sound that trivializes sexual assault 4 times. It’s still wildly popular |

| Police say ‘computer-generated voice’ behind swatting attempt of Marjorie Taylor Greene |

| ‘AI cannot be an excuse’: What happens when Meta’s chatbot brands a college professor a terrorist? |

| Sign up to receive the Daily Dot’s Internet Insider newsletter for urgent news from the frontline of online. |