In June, Ricky Llamas was driving back home from the Texas border town of Brownsville when he, his sister, and a friend were held at a U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint. This was at the height the Trump administration’s reviled family separation policy, and in protest, they had refused to answer the border agent’s question about their citizenship. Doing so was within their legal right. Still, the agent told him to pull over for additional questioning.

As 90 minutes passed, Llamas, a naturalized U.S. citizen, said he began to worry that his act of resistance in solidarity with other immigrants would end with him being held indefinitely.

“I had read that they could detain you for around 20 minutes and I thought, ‘Man this has been a lot longer.’ I’m starting to wonder, ‘Are they actually going to detain us indefinitely?’” Llamas said. “Who’s going to come and stop them?” (A spokesperson for CBP did not respond to the Daily Dot’s request for comment.)

Though Llamas and his passengers were eventually told they were allowed to leave the checkpoint, others encountering CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents across the U.S.—be it during designated stops or random workplace raids—may not be as lucky to leave such a situation. Llamas had intentionally recorded the agents throughout the interaction, but those who don’t anticipate an immigration agent run-in might not know who to contact for help, nor have as long a time in detainment to weigh their options.

In order to bridge that preparedness gap, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas has developed a smartphone app called MigraCam, which livestreams recorded encounters to emergency contacts. The organization also teaches communities how to use the app during its “Know Your Rights” clinics across the state.

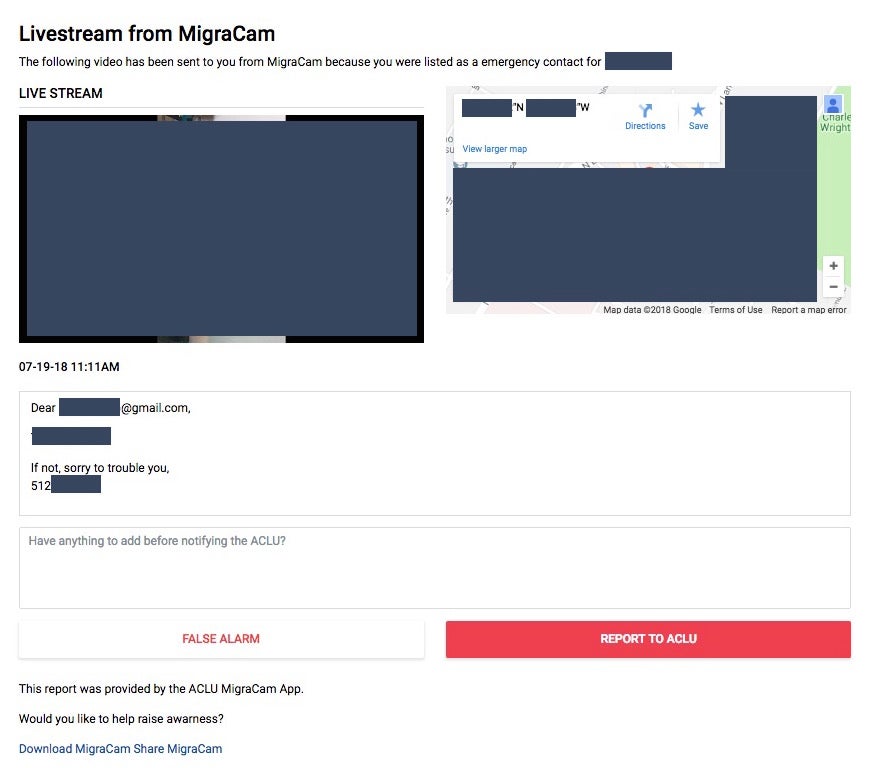

The MigraCam app, launched in April and available for free from the iTunes and Google Play app stores, allows users to livestream interactions with immigration agents and send a link of the stream to three preset emergency contacts, along with the user’s location. After the video is recorded, the emergency contact has the option of reporting the recording to ACLU Texas’ legal team for review, to see if the user’s rights were violated by agents, or to flag the video as a “false alarm.” The app provides additional support with a “Know Your Rights” rundown and deploys location-specific immigration alerts to the user, such as law changes. All features are available in English and Spanish, depending on the phone’s language setup.

Cynthia Pompa, advocacy manager for the ACLU Border Rights Center, told the Daily Dot that ACLU Texas developed the app in order to help create a community accountability tool in regards to law enforcement. While the ACLU has released similar applications for recording police, the MigraCam app is part of a larger safety strategy to help undocumented people know what to do when they encounter border patrol or ICE. And while a similar app by nonprofit United We Dream called Notifica also alerts emergency contacts with messages and a location, MigraCam helps document an ICE raid or border patrol stop with a visual record of the encounter.

More specifically, Pompa said MigraCram was created for undocumented people across the country, and people living in the 100-air-mile border zone that CBP is allowed to patrol around the U.S. Some entire states fall into this jurisdiction, such as Florida, Hawaii, and many East Coast states, while some of the country’s largest cities—New York, Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago—are encompassed by it.

“The main focus is to provide people a tool to alert their family members if something is happening, and the second is having that option to share [the video] with us if that’s what they want,” Pompa said.

MigraCam is fairly straightforward to set up. When first opened on the device, the app gives the user an intro of its services, then prompts the user to provide their phone number, then the phone number or email address of at least one emergency contact. Users are then prompted to provide a 300-character message to be sent when the stream is deployed.

At the end of the setup, the user is presented with a demo of the 10-second delay that they’ll see if they do start livestreaming to contacts (in the Daily Dot’s trials with the app, we found a 20- to 40-second delay regardless of WiFi or data usage): a red screen counting down from 10, stating they can “TAP ANYWHERE ON THE SCREEN TO STOP.” This notice will begin counting down each time the user opens the app, though users can stop the countdown and proceed recording at any time by tapping the red “record” button.

Within seconds of starting a livestream, the link to the stream is sent to the emergency contacts. From the link, emergency contacts can access the stream, the coordinates the stream is being sent from, and the pre-written message from the sender. Once the livestream ends, it can still be viewed from the emergency contact’s link as archived footage. The video is also saved to the user’s camera roll. Again, the contact can then flag the video to ACLU Texas or report it as a false alarm. ACLU Texas said it doesn’t comment on videos submitted as a result of the livestream, nor does it track video submissions deployed to family members.

In order to make the app more accessible to immigrant communities—it has been downloaded more than 14,600 times since its launch—ACLU Texas has begun teaching attendees how to use the app at the “Know Your Rights” clinics it holds in Rio Grande Valley and El Paso. This is particularly helpful to family members of mixed-immigration status who might be better able to assist their undocumented family members in a crisis. Pompa said that even if people don’t end up needing to implement such a plan, having one will at least provide comfort to those vulnerable in run-ins with immigration enforcement.

“Many times, perhaps the teenager is a U.S. citizen who also feels a little more confident [with recording CBP and ICE] and who also wants to have a role in this, and it’s just important to know if something were to happen, if ICE were to show up at your door, who’s going to be the one starting to record,” Pompa said. “Just doing a run-through makes people just feel really confident, and it also gives you a tool to feel like you’re not alone.”

After Llamas’ encounter with the border patrol in June, he said he filed a report with CBP and ACLU Texas; someone identifying themselves as border patrol had also called his mother’s home and threatened him. But first, he uploaded his video of the stop to Facebook as his first line of defense, and it has since gone viral. He told the Daily Dot that he wanted to show his protest of the family separation policy, but also be protected by documentation should his refusal continue to cause trouble for him and his family.

“I felt that if I kept quiet and this never got out, then people would feel empowered to continue to harass my family and maybe even make good on their threats. And by going public with it, I was at least in the public eye, and that offered at least some modicum of protection,” Llamas said.

This is the same principle behind MigraCam: A way to provide the immigrant community with some safety and comfort when there is so little to be found.