In a country fiercely divided along party lines, Americans of all political stripes agree on one thing: The juvenile justice system, which often serves as pipeline to the adult prison system, needs a complete overhaul.

Part of a major Internet campaign launched this month, data scientists and juvenile advocates at the Youth First Initiative identified 80 state-run facilities providing long-term, post-adjudication confinement of more than 54,000 adolescents. Typically housing 100-300 prisoners, these facilities have been described by leading criminal justice scholars as both cruel and dehumanizing to residents, some young as 12-years-old.

“In the last decade, formerly incarcerated youth, family members, community leaders, and advocates have launched campaigns to shut down youth prisons in states like Louisiana, New York, Mississippi, Texas, DC, and California,” Youth First said in a statement.

“I remember like it was yesterday. I just cried in my cell for hours and hours.”

“Today, several campaigns with bipartisan support are seeking to build on these victories by promoting a new model of youth justice in their states. These campaigns aim to replace youth prisons with successful, research-based programs that are far more effective at rehabilitating youth, and which cost an average of only $75 per day per youth, compared to $241 per day per youth for incarceration.”

According to polls conducted by Youth First in late January, 77 percent of all Americans believe that, in handling youth crime, the U.S. government should increase its focus on prevention and rehabilitation—a stark shift for the largely punitive youth incarceration complex. This desire to improve conditions crosses partisan lines, with 79 percent of Democrats, 71 percent of Republicans, and 80 percent of independents urging reforms.

The alienation of family members is a chief concern for these respondents. Many children after being arrested and convicted of crimes are housed in prisons more than 100 miles from their closest relatives. Polling shows that 89 percent of Americans favor rehabilitation plans involving the family of incarcerated youths.

Other key findings include, according to Youth First:

- Americans favor (83 percent) providing financial incentives for states and municipalities to invest in alternatives to youth incarceration, such as intensive rehabilitation, education, job training, community services, and programs that provide youth the opportunity to repair harm to victims and communities.

- 73 percent of Americans agreed that youth can be taught to take responsibility for their actions without resorting to incarceration.

- A majority of Americans believe that youth prisons should be closed, and that the savings should be redirected to community based programs, including intensive ones for youth who pose a serious threat to public safety, and that number climbs to 67 percent with Americans age 18-29.

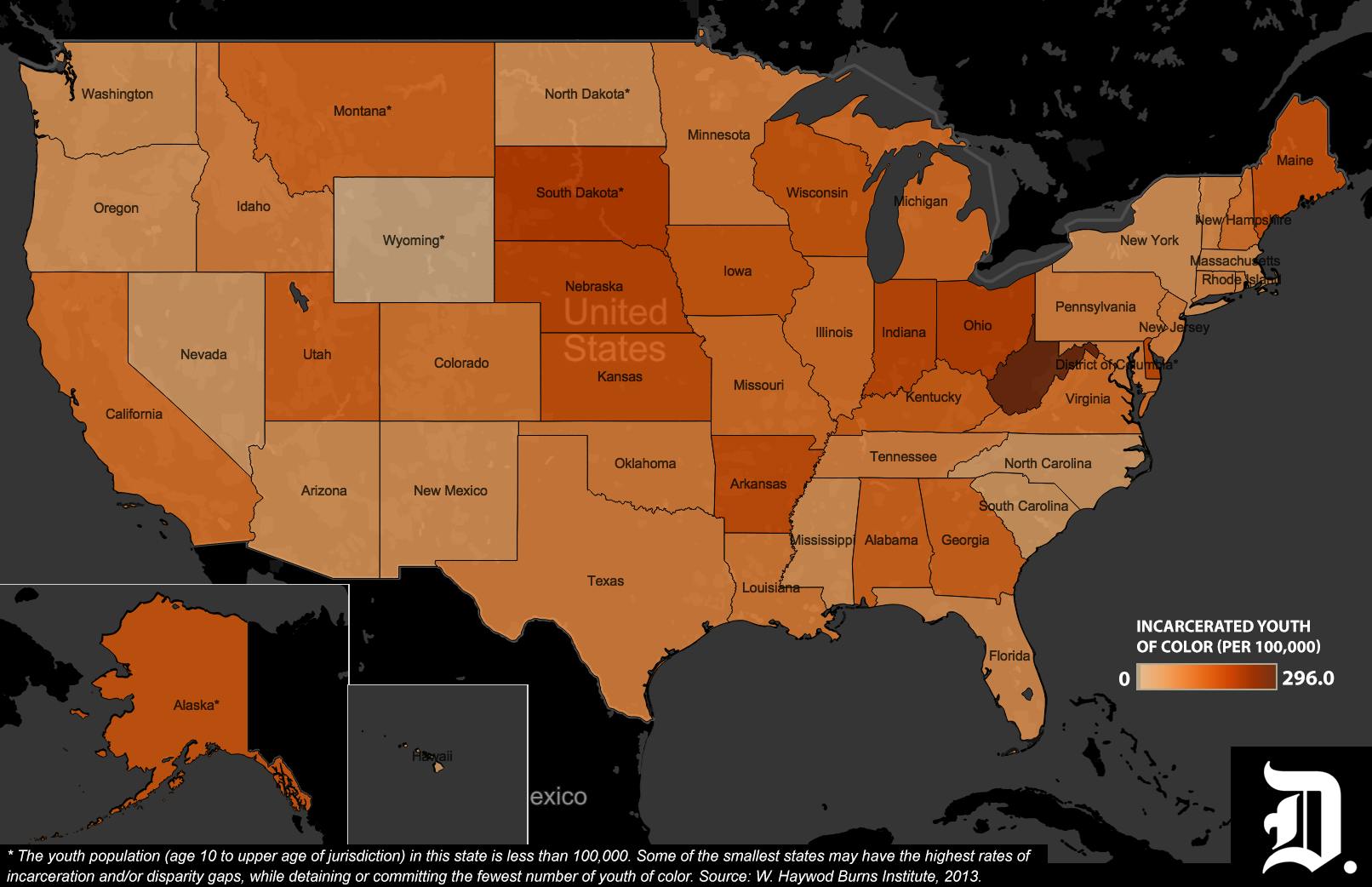

- 70 percent of Americans favor requiring states to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system. Young people of color are much more likely to be incarcerated despite committing roughly the same level of juvenile crime as white youth.

In a teleconference, Youth First President Liz Ryan told the Daily Dot that in their current state youth prisons are both dangerous and unjust. “There is a prevalence of physical and chemical restraints, high suicide risk, sexual and physical abuse, and solitary confinement,” she said. Ryan added, “Youth of color are much more likely to be incarcerated than white youth, even when charged with similar offenses and despite the fact that youth engaged in the same level of juvenile delinquency.”

The racial and ethnic disparities are indeed startling: While African-Americans make up roughly 12-13 percent of the U.S. population, their children are five times more likely to serve time in a juvenile prison.

Above all else, Ryan said, the U.S. juvenile justice system has failed entirely in its core mission. “Youth who’ve been incarcerated in youth prisons experience high recidivism rates, and this substantially increases the likelihood that they will be incarcerated in the adult criminal justice system.”

A product of the 1800s, the U.S. juvenile justice system was initially designed to consider the unique status of adolescents under U.S. constitutional law. As researcher Dr. Ashley Nellis notes in the introduction to her 2015 book, A Return to Justice, “The hallmarks of this approach appreciated the fact that youth cannot fully understand the consequences of their actions and are therefore worthy of reduced culpability.” But this vision, Nellis writes, was “slowly dismantled and replaced with a system more like the adult criminal justice system, one which takes no account of age.”

“Even though youth incarceration has decreased in the last decade, states are still relying on youth prisons, a relic of an 1820’s justice system, that is harmful, racially biased and obsolete,” added Ryan.

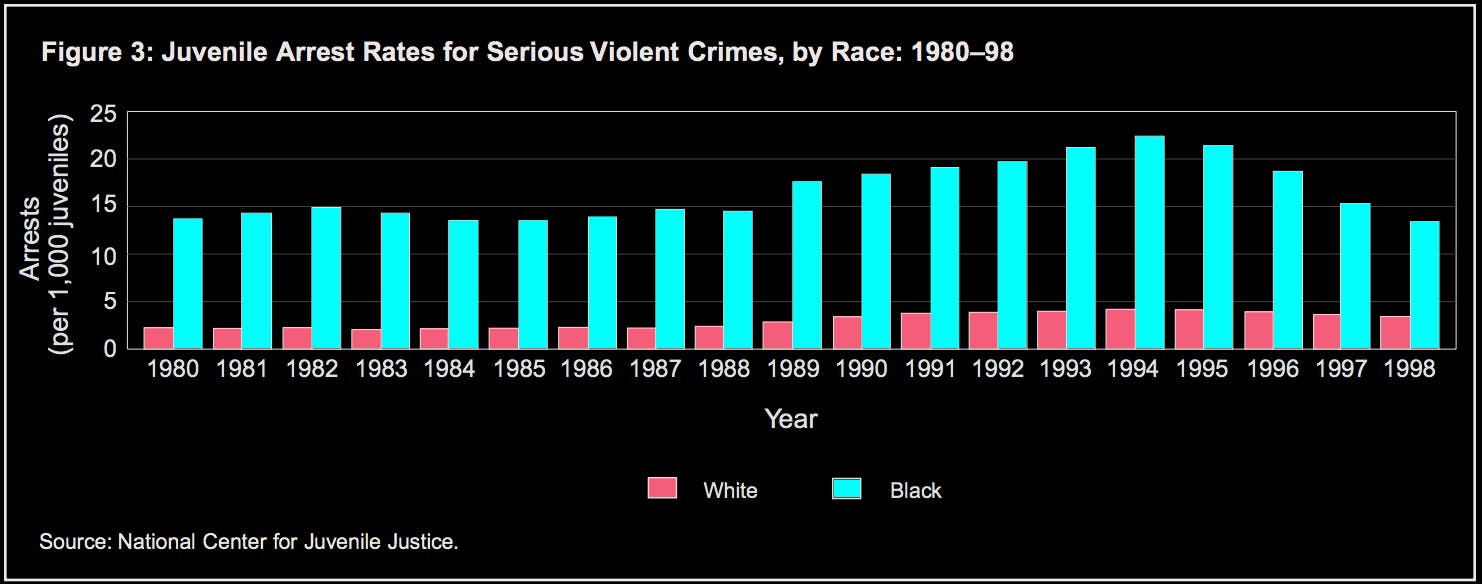

In 1980, the arrest rate among black juveniles ages 12-17 was 6.1 times the rate among white juveniles, according to criminal justice expert Dr. James Lynch. In 1981, that figure rose to 6.6 before declining by roughly half in the late 90s. “Although this decrease was pronounced, it was not consistent throughout the period,” Lynch noted in a 2002 white paper for the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

A 2012 study conducted by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Human Rights Campaign found the handling of incarcerated youth in the U.S. tantamount to torture, specifically with regards to the use of solitary confinement as a punitive measure. The 127 youth prisoners included in the study spoke of a wide range of inhumane conditions impacting their physical, developmental, and psychological well being.

Confined to a cell roughly the size of a parking space, alone, for up to 22 hours a day, many of the former prisoners described being deprived of access to physical and mental health care services, having their movement restricted in a way that prohibited physical exercise, and routinely being denied access to educational materials.

Solitary confinement is regarded as a form of torture by countless scholarly studies and international bodies, which include experts on the effects of stress on the human psyche. Approximately half of all suicides committed in U.S. prisons occur in solitary confinement.

Fifteen of the former child-prisoners interviewed in 2012 admitted “cutting or harming themselves or thinking about or attempting suicide one or more times while in solitary confinement,” the report found. Others described “hallucinations, losing control of themselves, or losing touch with reality” when subjected to prolonged isolation.

“There is a prevalence of physical and chemical restraints, high suicide risk, sexual and physical abuse, and solitary confinement.”

Da’Quon Beaver, a youth-prison activist, described his experience as an inmate in multiple Virginia facilities during a call with reporters on March 3. “There are fights and riots, threats of sexual abuse. The [correction officers] treat the residents any kind of way, because they say the residents don’t have rights,” he said. “Once you’re locked up, you lose all [your] rights.”

Beaver added that residents with mental illness were denied treatment and instead “placed in isolation units just because of their disabilities, not for getting in trouble or anything.” Educational opportunities were slim, and “there were weeks where there’s no school because of a lack of security staff.”

The worst of the suffering, Da’Quon said, arose from the long periods of isolation, which prevented him from visiting with his family. “In the most important part of my life,” he said, “when I was supposed to be learning how to become an adult, I was taken far away from my home, far away from my family, the people who were close to me.”

“I remember like it was yesterday,” he continued, describing one Christmas night he spent separated from his family due to a lockdown at the facility. “I just cried in my cell for hours and hours.” When authorities lifted the lockdown “there were only five youths in the visitation room” out of a population of 300, he said. “I knew right then that I wasn’t the only child who cried last night, and there were going to be more kids crying in the future because of not being able to see their parents.”

Photo via Flickr/Thomas Hawk (CC BY-NC 2.0)