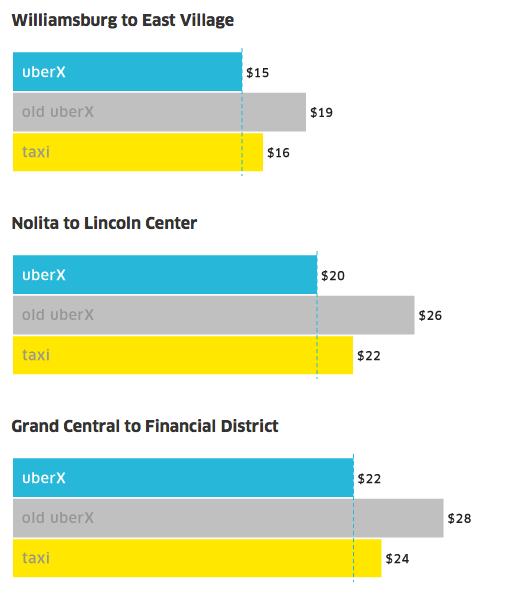

This week, Uber made a fateful announcement: The company is slashing the price on its ridesharing service UberX in New York City by 20 percent. In and of itself, this isn’t all that big of a deal. Uber constantly tweaks the price of a ride on its service in order to meet demand. What is a big deal, however, is that this price cut officially made UberX cheaper than taking a cab.

The offer is for a limited time only, although the San Francisco-based company has pledged to make the promotion permanent if enough people start using it.

The goal here is to increase adoption. If UberX is cheaper than taking a cab, then presumably more people will use UberX, and reducing prices will earn the company more money in the long run. If the price cut doesn’t drum up enough new business to make up for the reduced profit from each trip, the company can just move prices back to their original level above standard cab rates and simply bask in the publicity.

Uber has taken similar tactics before. And in some of those instances, the company has paid drivers back to recover some of their lost revenue. In New York, Uber isn’t doing any such thing, likely because it believes undercutting cabs will be a major advantage in growing the business and, at least in Boston, cutting its fare actually resulted in drivers increasing their hourly income by 22 percent.

Dave Sutton, a spokesperson for Who’s Driving You?, an iniative by the Taxi, Limousine & Paratransit Association that calls for the stricter reguation of services like UberX, estimated that, across the country, Uber’s costs are 30 to 40 percent lower than taxis becuase ridesharing drivers oftern are subjected to the same insurance and licensing requirements and fees. These comparatively lower costs can sometimes be passed on to the consumer in the form of cheaper fares.

Pricing is especially important for Uber in New York—at least, relative to places like San Francisco. In New York, there are generally plenty of cabs to go around. That means Uber needs to find a new way to compete with the city’s ubiquitous yellow cabs. With this rate cut, Uber shows that it’s going to have to do so on price—an area where Uber has an advantage. In short, the company has just initiated a price war against a competitor that can’t fight back.

• • •

For virtually as long as there have been taxis, there have been taxi regulations. Horse-drawn taxis first appeared on the streets of London and Paris in the early 17th Century. By 1635, King Charles I of England ordered that all taxis on the city’s streets be licensed by the state “to restrain the multitude and promiscuous use of coaches.”

Regulation in the United States came after the number of taxis exploded during the Great Depression, which threw vast swaths of car-owners out of work. Uninsured cabbies regularly got into accidents that injured passengers without paying to cover their injuries, and the high degree of competition shrank profit margins to the point where drivers were working 16-hour days to barely eke out a living. The whole system was basically a mess.

As a U.S. Department of Transportation official wrote in 1933:

The excess supply of taxis led to fare wars, extortion, and a lack of insurance and financial responsibility among operators and drivers. Public officials and the press in cities across the country cried out for public control over the taxi industry.

The response was municipal control over fares, licenses, insurance and other aspects of taxi service.

As a result, most major cities across the U.S. instituted regulations imposing limitations on the number of taxis allowed on the streets. Artificially constricting the supply of cabs girded against flooding the market with operators and ensured drivers a consistent income. It also gave municipalities the ability to easily and effectively impose safety and consumer protection regulations, like insurance requirements, background checks for operators, and requirements that drivers drop people off anywhere within city limits that they want to go.

However, the regulatory scheme also posed a problem: How do you prevent cab companies—which were effectively being granted entry into tightly controlled oligopolies—from charging exorbitant rates to consumers who had nowhere else to turn? Cartels of cab operators could raise prices in tandem and squeeze all but the wealthiest riders out of an integral part of the transportation system.

The solution was for governments government to set the prices that cabs can charge for a ride. Those rates vary from city to city and have gradually increased over time, but one thing remains consistent: They are decided by government regulators rather than the cab companies or the drivers themselves.

• • •

In New York City, it costs $3 to start the meter and an extra $0.50 is added for ever one-fifth of a mile or 60 seconds that the vehicle is sitting in traffic. Surcharges are also tacked on for late-night rides or during rush hour. These rates are set by the city’s Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC), which reviews them every other year. Inquiries into changing rates can also be triggered by a petition from the cab industry. The last time they were changed was in 2012; before that, in 2006.

Uber, on the other hand, has considerably more freedom in determining what its drivers can charge because its cars are considered “for hire,” putting them into the same category as limousines, not yellow taxis. Not only can the company nudge overall rates up or down in a given area whenever it wants, but it consistently implements something called surge pricing, where rates are automatically boosted when more people are likely to need a lift, like when bars are closing on Friday and Saturday evening.

During a snowstorm that battered New York late last year, Uber pushed prices up to eight times their normal rates. It also activated surge pricing during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which sparked a citizen backlash against Uber. The company will no longer bump prices during emergencies in the state, however, thanks to a deal reached Tuesday between Uber and New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman.

#BREAKING: My office has reached an agreement with @Uber to cap pricing during emergencies, a thoughtful application of NY law to new #tech.

— Eric Schneiderman (@AGSchneiderman) July 8, 2014

This sort of price variation would never fly in the taxi world. Even though taxis are privately owned, they’re viewed by regulators as part of the public transportation network. As such, their pricing should be consistent a subway fare. While Uber can shrug off charges of ?high-tech gouging” or intentionally keeping drivers off the streets to restrict supply and justify increases in the price of a ride, taxis don’t have the option try new pricing models on a whim.

Until recently, inflexibility in pricing hasn’t been much of a problem for taxi drivers. All that’s been required is a gradual upward drift over time to keep pace with inflation and the overall cost of living. Margins in the taxi business may be thin, but at least they’re consistent. Due to that consistency, the medallions that allow someone to drive a cab are a highly prized commodity, at least in major cities like New York, where a recent auction saw medallions going for nearly $1 million.

Only a small number of the drivers have medallions themselves, most lease medallions from cab companies or individual owners for a fee.

New York cab medallions have historically been a great investment. They’ve gone up in value over 1,000 percent since 1980, making it a better investment than gold by greater than a factor of five.

However, there’s some evidence this is starting to change. Even before Uber announced its NYC price hike, medallion prices in the city have actually started dropping. Granted, the decrease in June was only $5, but that’s still out of the ordinary and may be an omen for what’s to come. In Chicago, where cab companies are suing the city for allowing ridesharing services like Uber to operate without being subjected to the same regulations, medallion prices have seen an even more pronounced drop.

Decreases in medallion prices aren’t universal—Boston, for example, hasn’t experienced it—but it is an indication that, in some places, these new entrants into the taxi market are having an effect.

This doesn’t mean that Uber is always in direct competition with taxis. Last year, Uber received approval from the TLC to allow users to hail officially licensed city cabs from its app. Added to that, the company’s ridesharing service UberX, is full of licensed ?for hire” drivers; while subjected to less regulation than regular taxi operations, they’re far more tightly controlled than what’s required in the rest of the country.

A representative from Uber did not respond to emailed questions from the Daily Dot.

Even so, by dropping its UberX prices, Uber seems to want to get an albeit small piece of yellow cab revenue, while trying to push more customers over to its other service. Unless city officials decide to drop the prices for a cab fare—something that’s never happened in New York City and is exceedingly rare anywhere in the country—it’s going to be virtually impossible for taxi drivers to respond with a price cut of their own.

Update: The story has been updated to include comments from Dave Sutton.

Photo by PublicDomainPictures/pixabay (CC0 1.0)