Tech likes to tell its own story. The prevailing story—so often of a precocious young white man, the obstacles in his path, his eventual ascendance—is its own sort of monoculture. In the process of creating things, Silicon Valley grew a legend too.

But there are many, many more stories.

On Thursday night, those stories echoed through Rackspace in San Francisco, where a cross-section of tech’s most underrepresented members gathered to ask and answer one question: What does it mean to look like an engineer?

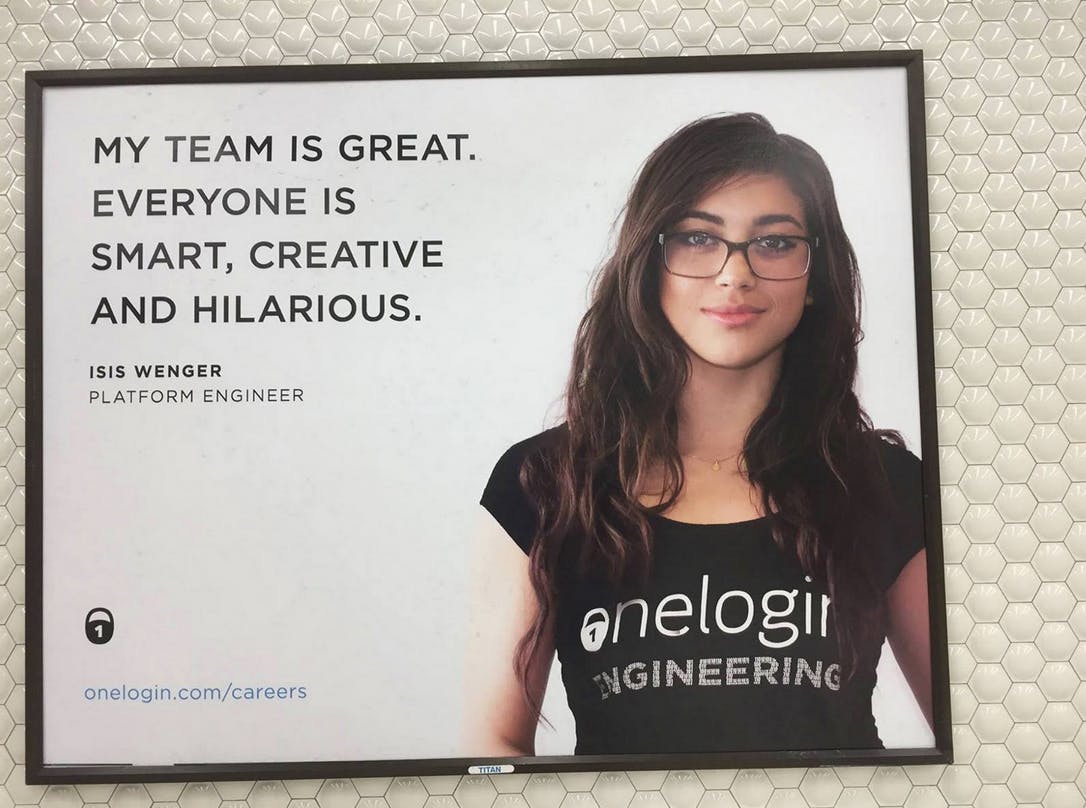

The hashtag campaign #ILookLikeAnEngineer started off as a blog post by Isis Wenger, a full-stack engineer at OneLogin, who agreed to pose for a company ad and was quickly thrust into an unwanted spotlight.

The recruiting ad was immediately criticized. Detractors reasoned that because of her looks and gender, she must simply be a model, or a product of “weird, haphazard branding.”

In response to her critics, she encouraged others to tweet #ILookLikeAnEngineer to prove that there are more than just white men working in the industry. The hashtag picked up steam, evolving into a movement in its own right, as underrepresented minorities in the tech workforce transformed it into a rallying cry for diversity in Silicon Valley.

The hashtag erupted on Twitter, smashing stereotypes and celebrating women in tech. People from all backgrounds began sharing selfies with the hashtag, and it grew so popular, women in other science and tech fields adopted it to show their own diverse perspectives.

Wenger didn’t expect such a large outpouring of support. Though she might be considered the “face” of the movement, she shrugs off the spotlight, instead giving credit to the people who helped it take off.

“I’m so overwhelmed at the amount of positive attention that this is generating,” she said in an interview after Thursday’s event. “Other people are speaking up and sharing their stories, and I think that’s what’s important.”

Many of those who spoke up packed the house at the Thursday evening event, strategizing on how to raise money for at least one massive #ILookLikeAnEngineer billboard to be erected in San Francisco.

As six speakers addressed the room, breaks for clapping, cheers, and snaps underscored just how common their shared experiences were.

Dominique DeGuzman, Twilio engineer and city director of Lesbians Who Tech in San Francisco, described a harrowing experience at a bar in the city when a man refused to believe her when she said she was an engineer.

“I don’t think it’s normal that someone challenges you only because you’re female or only because you’re a person of color,” she said. “I don’t think that it’s normal for someone to ask for a second review on my code when a male counterpart—a male intern—doesn’t get the same type of code review.”

Wayne Sutton, general partner at BUILDUP VC talked about an incident on a boat during an event with investors, founders, and other industry types. He was the only black man. No one shook his hand or spoke to him.

Alicia Morga, founder and CEO of No. 8 Media is one of the only Latino homeowners in her community, and at Thursday’s event, explained how she feels stereotyped and discriminated against in San Francisco. While jogging through her neighborhood, she said “excuse me,” and a white family heard her, but refused to get out of her way.

“I thought surely they would make room on the sidewalk for me. I ended up running right into their [daughter],” she said.

Silicon Valley likes to use the term “unicorn” to describe companies with valuations of $1 billion or higher. For Erica Baker, build and release engineer at Slack, being a unicorn in tech means being a black woman, because there are so few.

“There’s a thing called ‘othering,’” Baker said, describing the way people view or treat individuals in a way that can create positions of domination and subordination. “Unicorns are beautiful and majestic and rare. But when you’re that one unicorn in a whole pack of horses, all the horses treat you differently, you start to feel othered.

“Instead of that beautiful and unique and majestic unicorn, you start to feel different, alienated, isolated, and alone.”

For self-taught engineer Leslie Miley, his journey from high school dropout to product safety engineering team lead at Twitter has been replete with discrimination as a black man in tech. Even at Twitter, the platform on which movements such as #ILookLikeAnEngineer and #BlackLivesMatter launched, he faces bias and prejudice.

“What Twitter does on the outside sometimes does not reflect on the inside,” he said.

“What Twitter does on the outside sometimes does not reflect on the inside.”

Twitter is among the least diverse tech companies that have released diversity statistics, particularly among the technical teams. The company employs just 49 black people out of the 2,910 employee workforce, according to a July report. The company also came under fire for throwing a “Twitter Frat House” party earlier this summer, while in the midst of battling a gender discrimination lawsuit.

Miley cautioned against falling into the trap of being “tokenized,” appearing in brochures or advertising to highlight companies’ “diversity.” He also warned against the dangers of keeping your head down just to retain a comfortable job and stock options.

One particularly striking quote resonated with the audience, and Miley attributed it to his father, who he said was involved in the Black Panther movement: “White people only understand one language of black people, that’s the language of disturbance.”

Sutton and Miley both mentioned that the conversation around diversity didn’t even exist five years ago. It’s only recently that companies are acknowledging the bias, sexism, and racism that exists throughout the entire industry’s structure—blind resumes and recruiting diverse college graduates mean nothing if the culture is a toxic waste dump of frat-like parties and constant reminders of tokenism or, worse, outright discrimination.

This week, Apple and Intel both shared new workforce statistics that illustrate the disparity of minorities under their employ. Apple’s data barely showed any overall improvement despite hiring more women and people of color than ever before. And Intel touted its multi-million dollar efforts that doubled its diverse hires in just six months. Less than one month ago, Intel’s CEO cited a system of “meritocracy” as the justification for a large round of layoffs, using a word that’s synonymous with Silicon Valley hubris.

The audience at Thursday’s event was overwhelmingly female, and it was apparent that every person there believed wholeheartedly that the industry needs to change. When asked how companies can improve diverse hiring and inclusion within the existing structure, a resounding answer was clear—but perhaps wasn’t heard by the people who need to hear it the most.

“When you go to these companies, ask the C-level executives what they personally do for diversity in tech,” Baker said. “Not how much money their companies spend, not what they sign off on. Ask them what they personally do.”

When you go to these companies, ask the C-level executives what they personally do for diversity in tech.

Baker specifically highlighted her own CEO, Slack’s Stewart Butterfield, and Aaron Levie, CEO of Box, as examples of leaders who are taking the issue seriously. She also mentioned Twitter’s Jack Dorsey as an example of a leader who is both aware of these issues and speaks out for change. (Dorsey is one of a handful of prominent tech industry moguls who regularly tweets about #BlackLivesMatter, and protests around his hometown of St. Louis, Mo.)

But just because a company leader believes in improving inclusion, it does not mean culture can change overnight.

“There have been many events and many situations at Twitter where I’m reminded that A, I’m not an engineer as some people like to say, and B, that I’m actually a black person,” Miley said.

Still, as Sutton pointed out, hashtag activism only goes so far. What happens when the tag stops trending? In order to enact real change, he said, it’s the investors and industry leaders who need to change first.

“How many memes have we seen? How many hashtags have we seen about diversity in tech?” he said. “Here today, gone tomorrow. This could just be another hashtag that’s over next week.”

The speakers’ stories were heartfelt, but for any minority who has worked in technology, they’re far from shocking. These shared experiences were potently commonplace for Thursday’s attendees.

And yet it’s these very stories that can truly kickstart change when they hit the right ears.

#ILookLikeAnEngineer began trending not because it was a unique experience, rather one that’s so prevalent that most women who tweeted it had a story to share. Perhaps one hashtag can make enough of the right people listen.

It’s not just Wenger’s story that will be displayed on a billboard above San Francisco. It will be the collective story you hear when you ask an engineer who is a woman of color: “What does #ILookLikeAnEngineer mean?”

For some, the prospect of staying in tech while withstanding constant harassment is difficult. In fact, 41 percent of women leave careers in technology after 10 years. But when asked why they remained in the industry, each speaker on Thursday night was intent on staying.

“I’m not uncomfortable in tech,” Morga said. “If I make other people in tech uncomfortable, then that’s their problem.”

Miley still believes working in technology is a way to contribute to something greater than himself—and movements like Black Lives Matter and others prove it.

“I took two years off to recharge my batteries, but I love tech and I love this industry,” he said. “There are very few industries where you get to change the world, and this is one of them.”

In a somber and somewhat hopeful admission, Baker recalled the two young girls whom she showed to the audience during her talk earlier in the evening. Baker is their aunt.

“I’m committed to fixing it for those two little girls you saw in the slide,” she said. “I don’t want this industry to be a shit show when they get there.”

Photo via hackNY/flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Max Fleishman