Something interesting happened on Thursday morning after the FCC released the full text of its order reclassifying Internet service providers under Title II of the Communications Act as a way to enforce net neutrality.

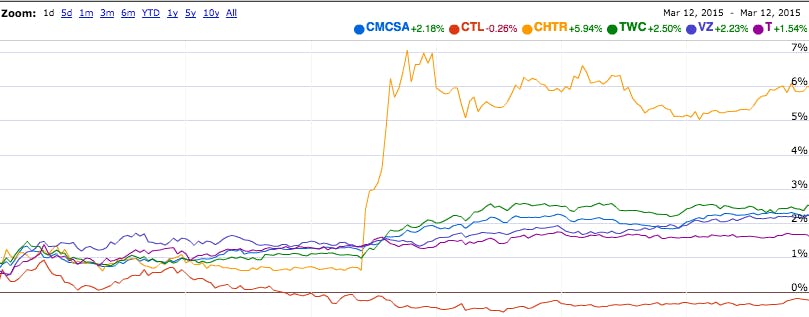

While big telecommunications firms like Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T have insisted, loudly and repeatedly, that reclassification would be terrible for business, nearly all the stock prices of major Internet service providers went up over the course of the day—with a sharp jump occurring right around the time the FCC released its rules.

The stock prices of most big cable companies—and wireless providers, whose data service is also included in the order—have ticked up by one-to-two percent. The stocks in the above chart belong to Comcast, CenturyLink, Charter Communications, Time Warner Cable, Verizon, and AT&T. The biggest outlier here is Charter, which shot up even higher due to rumors about the company’s potential acquisition of cable provider Bright House Networks.

It would stand to reason that the FCC’s reclassification order—which the commission approved in a 3-2 party line vote last month, but did not release the text of until this week—would be bad for large telecom firms because it robs them of the revenue stream of charging online content providers for access to a “fast lane” to consumers. If that’s the case, shouldn’t their stocks take a hit?

There are a few ways to explain what’s happening here. The simplest is that the FCC’s order isn’t a surprise. Investors have known not only that reclassification was coming for a long time, at least since President Obama spoke out strongly in favor it last year, but also of the 300-page order’s general tenor. As a result, they’ve already priced the risks arising from reclassification into their models. Whatever fluctuations are occurring in the companies’ stock prices in the wake of the release are probably due to other factors.

However, there are a pair of other explanations, one from a mainly liberal perspective and another from a conservative one, that are decidedly more interesting.

The argument coming from the left is that, through a process called forbearance, the FCC removed much of the regulatory teeth from its fundamental alteration in the way ISPs are regulated. The reason the FCC took up reclassification in the first place stems from a 2014 court decision that held the FCC couldn’t enforce net neutrality rules because it lacked the legal standing to do so. Since the Internet’s inception, ISPs have been regulated under Title I of the Communications Act. The court ruled that the FCC didn’t have jurisdiction over entities in that category, but added that if those companies were brought under the umbrella of Title II, which also includes utilities like phone networks, the agency could impose net neutrality to its heart’s content.

But there’s a lot more to Title II than simply requiring that companies treat all data flowing through their networks the same. There are also rules about things like how firms can set rates to consumers and how their products are structured.

The FCC’s reclassification order for ISPs contains a litany of exceptions, somewhere in the neighborhood of 700, to what Internet providers are allowed to do relative to other types of Title II networks.

FCC spokesperson Mark Wigfield insisted that these exceptions ensured the government continued to regulate the Internet with a light touch and were aimed at limiting the effect of the reclassification to the scope of net neutrality.

“There is no ‘utility-style’ regulation,” Wigfield argued in a statement. “The order bars the kinds of tariffing, rate regulation, unbundling requirements and administrative burdens that are the hallmarks of traditional utility regulation. No broadband provider will need to get the FCC’s approval before offering any price, product or plan.”

He noted that the order doesn’t preclude ISPs from setting their own rates, nor does it limit consumer choices in any way when it comes to broadband service. It doesn’t impose any new taxes or fees and it doesn’t do anything that would reduce incentives to invest in network upgrades or expand their coverage areas.

The forbearance of these rules, which have been hinted at by the FCC for months, means that many of the telecom industry’s fears about what could happen to their business under Title II could be assuaged. Comcast not being able to to charge Google or Netflix a premium to stream their content faster than the sites’ competitors is one thing, but the government telling the company how much it’s allowed to charge consumers is another thing entirely.

The industry’s fears about reclassification were never exclusively about net neutrality. Those concerns also had to do with all the other rules that could come with being regulated under Title II.

The more conservative argument, on the other hand, takes a considerably longer-term view. Communications network architect Dan Berninger—who spoke on behalf of a coalition of self-described “tech elders” including Electronic Frontier Foundation cofounder John Perry Barlow, Internet billionaire and outspoken Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, and venture capitalist Tim Draper—argued that the most important aspect of the FCC’s order has nothing to do with the application of any specific rule. Instead, he charged, the significant aspect of Title II reclassification is that it gives the FCC far greater authority to impose new regulations over Internet service in the future.

“I would say the stocks are probably going up because this [reclassification order] is a gift to large companies. It’s really only large companies that can play at the FCC,” explained Berninger, who contends that the FCC’s move is bad for the growth of the Internet as a whole. “It favors the lager firms because they’re the only ones who can afford the armies of lobbyists required to influence FCC policy. There’s no way a small company can pay attention to their customers and also hire all the lawyers and lobbyists necessary to get the most out of the regulatory process.”

Accusations of regulatory capture at the FCC are nothing new. Tim Karr, the director of the pro-net neutrality group Free Press told the Daily Dot last year that, by his calculations, 80 percent of all former FCC commissioners since 1980 went to work in the telecom industry after leaving government service—many of them lobbying their former colleagues on the commission.

The FCC’s chairman, Tom Wheeler, previously served as the chief lobbyist for both the cable and wireless industries before being appointed to his current job. Meredith Attwell Baker, who was Wheeler’s immediate predecessor helming the FCC, now runs CITA, the main lobbying arm for the wireless industry. Baker recently threatened at a recent commission meeting to sue the FCC over reclassification.

“Paying the salaries of those ex-commissioners isn’t cheap,” noted Berninger. “It’s something that only the big guys are able to do.”

The logic goes that, even if the FCC’s forbearance process did manage to leave the overwhelming majority of the telecom giants’ business untouched, the commission’s newfound ability to enact more regulation in the future would likely privilege big telecom companies, adept at shaping government policy to work in their favor, over other players in the market.

However, that the FCC may now have a newfound ability to create rules for ISPs, and lots of friendly input from the industry about precisely what those rules should look like, doesn’t necessarily mean the commission’s decisions will always fall in the industry’s favor. Private telecom companies, for example, have long lobbied in favor of putting roadblocks in the way of local government around the country establishing their own municipal broadband networks due to fears about having to compete directly with taxpayer-funded ISPs. These companies have successfully convinced 20 state legislatures to enact laws making it considerably more difficult, in some cases impossible, for municipalities to start their own ISPs or expand the scope of the ones that already exist.

Despite doubtless industry pressure on the FCC, the commission still recently voted to strike down a pair of those state laws and is poised to do the same to a litany of others. This example, combined with that of the reclassification order itself, shows that the commission does have a strong streak of independence from big telecom; however, that may not always be the case under future presidential administrations.

The trouble with the stock market is that there are a potentially innumerable set of factors that go into determining the movement of each individual stock price. What’s for sure is that the release of specifics of the FCC’s plan didn’t immediately cause analysts to conclude any newfound revelations about the specifics of reclassification will damage the earnings potential of big telecom companies to an enormous degree. While those companies are certainly protesting the government’s recent moves, Wall Street doesn’t seem to think it will be catastrophic to their bottom lines.

Illustration by Max Fleishman