There are few things more startling than seeing your private information released online. It makes you feel vulnerable and on-edge, knowing that anyone has the details necessary to throw a brick through your window at a moment’s notice.

The act, known as doxing, has become a popular tactic with activists and trolls alike, with members of Anonymous releasing details on KKK members to Gamergate members publishing the personal information of those the movement opposes.

While doxers sometimes use hacking or deception to uncover personal details about their targets, contrary to popular belief “most of the info is public,” according to one researcher who has spent years studying and participating in the practice of doxing. All it takes is the right person to put it all together for devastating effect.

Most of the information doxers use is already public.

The researcher, who asked not to be identified, has gained a deep understanding of the various strategies that are used to generate a profile on someone. He agreed to tell me how it’s done. I’m passing on what I’ve learned, so you can better protect yourself against this privacy-destroying practice.

For starters, imagine you say something online through one of your Internet pseudonyms that annoys or upsets another Web user. For whatever reason—revenge, or just for the thrill of it—that person wants to expose and embarrass you.

The doxer will begin his investigation at the most obvious starting point: your known postings and public messages. He’ll look for anything that may reveal your physical location or other usernames. For example, in one case the researcher recalled to me, a screenshot posted by a target accidentally revealed one of their alternative pseudonyms. From there, a trail can begin that may lead to more info—perhaps to your Facebook or Twitter account, or a rusty Myspace page that you’ve long forgotten about, from a time when you perhaps weren’t so careful with your online presence.

In a world where people have multiple accounts networked together, by simply using the search function on the social media site, or by punching it into Google, a small clue can quickly snowball into other pieces of info.

This piecemeal tactic is similar to what Andrea Shepard, a Tor developer, recently did to out a serial harasser of hers. In a detailed blog post, she laid out how she found links between several Twitter accounts, which all turned out to be the same person.

If you become a doxer’s target, the researcher told me, you not only have to worry about the personal information you post publicly online, but what your friends or other connections say about you. You may be very careful, but your friends might not be. In another rather convoluted example, a tweet sent from a friend to the wife of a target mentioned that they lived in parallel streets to each other. This friend, it turned out, was using his full name on his Twitter account. From there, it was possible to compare it with other information available about the target, and pin down an address.

Even if you’ve been particularly careful, there’s another early-stage approach a doxer will consider: big-data tools. Instead of searching through your Twitter feed manually, a doxer can finish the job far more quickly with one of the many free scraping tools available online. With all of the collected data, the doxer may start to notice trends, such as a preference for tweeting out news stories about a certain state, region, or area. This is the sort of observation that you probably wouldn’t be able to make if you were just checking individual tweets for sporadic details.

Once a doxer has a snippet of information on you, they use it to expand what they know. Typically, this process involves free public data sites, of which hundreds exist. These data brokers rip their data from open records, business directories and social media, or buy their data from other sites. A search with some sparse details can provide full names, email addresses, phone numbers, and other information.

Doxers want to cross-reference as much possible, looking for a credible match between the information provided by your various social media accounts and what is available from the data brokers. Again, all of the information has been public, either from data you or your contacts have published, or by the wealth of data available on via personal lookup sites. The researcher told me he has even referred to news articles and press releases to clear up information on locations, at least when the target is a public figure.

“Public data sites and social media: Google is the glue that binds them,” the researcher said.

Spokeo has dozens of dox records on me but limits me to removing 5 “In order to prevent abuse”… oh the irony. pic.twitter.com/yfEp6qg43m

— Cris Beasley (@crystaldbeasley) January 6, 2015

If not much new information is available on the public data sites, doxers often delve into illegal hacked databases that find their way into the open. Each time a major retailer, like Home Depot, Target, or Adobe, suffers a data breach, that information—names, email addresses, and maybe even credit card information—is often packaged and sold in shadier corners of the Web.

If a doxer find a correlated email address, that’s more information that can be followed up with other sites. In one story the researcher told me, a target had an old Yahoo email account—so old, in fact, that Yahoo had closed the account down due to inactivity.

This meant that the address was free to be registered again and used by anybody. After re-registering the email address, the doxer entered it into a number of large sites, checking to see if it was linked to any accounts, and then asked to reset the password when one came up. They got lucky with Amazon and managed to enter the account, which, conveniently, still had the target’s stored credit card information.

After scouring social media accounts and data sites, a doxer has probably made a fairly decent patchwork of your personal information. With these details—full name or email address can sometimes be enough—it is fairly trivial to then check if a target’s Social Security number is listed in a leaked database. If it is, your life may be about to get a lot more complicated.

As scary as that is, doxers have begun to use an increasingly popular tactic, according to the researcher, one that only requires knowing a target’s Internet service provider (ISP).

The researcher sent me a document that contains details on how to fool the call center staff of various ISPs. The document included the names of employees that doxers should pretend to be when calling up to obtain information, and the internal tools that each ISP uses, and what data they can be used to get hold of.

“Public data sites and social media: Google is the glue that binds them.”

In one instance, a doxer pretended to be a Comcast manager in order to get the name and address of a target. He asked the operator to use an internal tool to get information on the account behind the IP address. And, according to a transcript of the call the researcher provided, it worked.

A successful doxer can use social engineering techniques like this to get a full name, address, and phone number of the person paying for the Internet access. But this isn’t very impressive, according to the researcher. People who use this tactic will get what they need from the social engineering call, be that a full name or address, and leave the job at that.

The really big problems come when someone connects all of the dots and builds up a profile that covers all aspects of your life: old IP addresses, which mark your physical location over time; material from leaked databases; images; embarrassing personal details, and more. Talking about one particularity well-constructed example, “it meshed together perfectly,” the researcher said.

There are, fortunately, a few things you can do to minimize a determined doxer’s efforts.

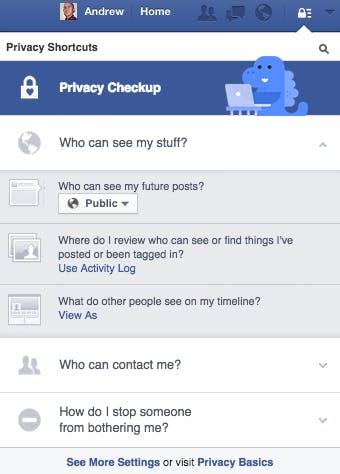

First, you can lock down your social media accounts with the tightest privacy restrictions available. This has become easier over the past couple of years, at least with Facebook. By clicking the “padlock” icon in the top right corner when you’re logged in, then “Who can see my stuff,” then “view as,” you can view what your profile looks like to friends, friends of friends, or even the general public, and then choose a level of privacy that you’re happy with. For albums and photos posted to your Timeline, you’ll need to go through each one and select your privacy setting.

When it comes to Twitter, you might not want to make your account private—that defeats the purpose for a lot of users. So if you want to keep it public, don’t link it with your other social media accounts; that means not using the same name on all your accounts or signing up for them with the same email address. That way, a potential doxer is going to have a harder time finding any other sources of personal details.

Once your social media presence has been dealt with, you might want to tackle whatever personal information is available about you on the data sites, such as your address history and contact information. This can often be done directly on the website itself, usually via a form that you need to print, sign, and then email back over. The results can take more than a week to take effect, however.

You may also want to address that long forgotten MySpace profile you made years ago (or, for that matter, any other old or obsolete social media accounts). Although it may not contain any information that indicates your current whereabouts, it can still be useful to a doxer trying to build up a picture of your past, or to simply harvest embarrassing photos. Profiles are very easy to delete via the MySpace website, even if you’ve forgotten any of your login details.

More generally, get into the mindsight of good security practices: Don’t use the same password on different websites; don’t save your credit card numbers into services, such as Amazon; ask friends to delete posts that reveal information about your personal life; and just be hyper-aware of what you are putting out there in the public space.

Of course, this is all easier said than done. Ken Gagne from Computer World recently checked to see how easy it was to remove his own results from various data broker sites, with a varied level of success. And doxing is especially reliant on information that victims are voluntarily broadcasting themselves. That is not to blame them for wishing to share their lives with others online, but it is a stark reminder that what you say on the Internet can be used against you.

Photo via JD Hancock/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed