Open Bernie PB on the day of an election and you’ll see pinpricks of caller activity in the form of bird symbols flying across the screen on a map of the United States, even in remote areas like Guam.

In the Michigan primary alone last week, over a thousand calls were tracked.

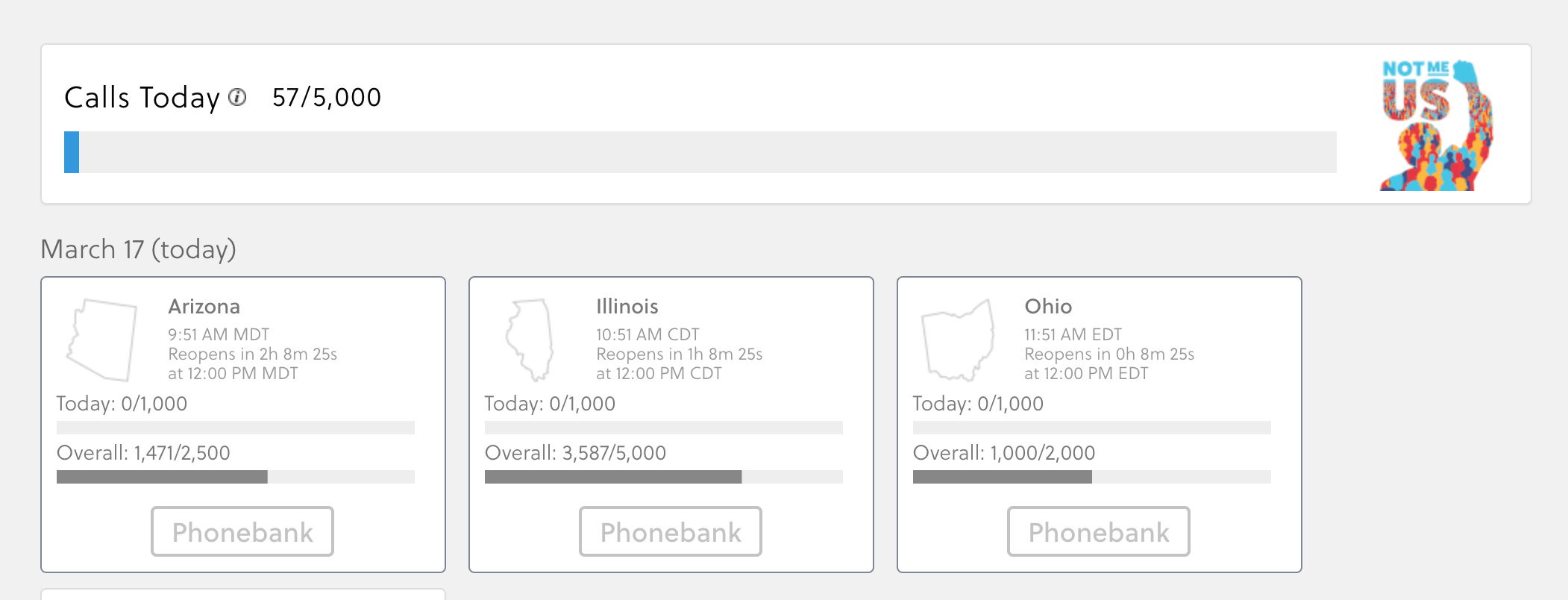

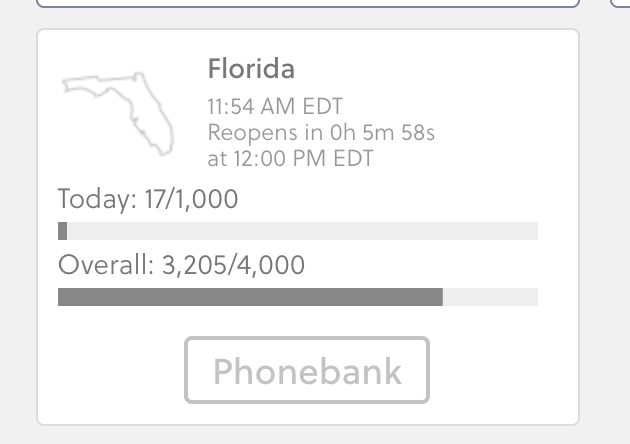

With primaries across the board today, callers are focusing on Florida, Illinois, and Arizona.

It’s hard to believe that this phone banking tool, which has become an extremely useful asset to the campaign, was created by two college students who just wanted to help Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and thought the process could use a facelift.

“We thought it would be fun if we could watch a live map of calls as they happen,” says developer Laksh Bhasin, who co-created the Chrome extension with developer Sean McFarland during the 2016 election when the two were college students in California. They wanted to be able to project a map of calls happening at phone banking parties.

“Over time, it became a much bigger project.”

“We were a bit underwhelmed at the time with how student energy was being translated into impactful work on the campaign,” McFarland recalls. Bhasin and McFarland thought it would be helpful to create a Chrome extension that tracks how many phone banking calls someone has made through the Bernie Sanders dialer, something volunteers would not normally see. In addition to logging the number of calls and adding them to a live map, Bernie PB also features leaderboards and various achievements that can be unlocked by making more calls for the candidate.

The leaderboards were intended to encourage friendly competition between different schools.

Phone banking is an electioneering tool as old as modern campaigning itself. In its present form, campaigns set up dialer systems like ThruTalk and CallHub that automatically dial voters in specific states. Volunteers making these calls are provided with a script they can read to try to convince a candidate’s supporters to make it to the polls to vote and to provide them with correct information about polling places.

It’s especially important in grassroots organizing, where direct person-to-person contact is the most effective way to get a voter to actually cast their ballot—and voter suppression runs amok.

And at a time in the primary where people may be less likely to canvass because of coronavirus concerns, phone banking is essential.

Initially, few people outside of Bhasin and McFarland’s circles used the app—until the subreddit r/SandersForPresident discovered it. That’s when BerniePB took off. The Sanders campaign even embedded the extension onto their own website to display a caller leaderboard.

As a free extension that works on top of the campaign’s calling tools, the public data BerniePB tracks and encourages is invaluable. Much of the privately-owned tools that any campaign needs in order to organize effectively cost a lot of money, which inhibits grassroots organizing. For example, virtually all campaigns use the expensive VAN (Voter Activation Network) to track field organizing information, and VAN has a monopoly on the industry.

As an activist who has worked on grassroots campaigns like support for the San Francisco Community Housing Act, Bhasin cites the barrier that money creates to small campaigns—even when it comes to essential campaign infrastructure tools.

In 2019, the political campaign of District Attorney Chesa Boudin got a taste of this unbalanced power dynamic when consultant Jim Stearns revoked the organizers’ access to VAN for several hours prior to the election. When it comes to small campaigns like Boudin’s that can be decided by just a handful of votes, every hour of outreach matters, and losing access to a tool that takes up much of a campaign’s financial resources can make or break a race.

The tech industry’s generally cavalier “move fast and break things” attitude set the tone for the 2020 primaries. In Iowa, several developers associated with the Hillary Clinton campaign released a largely untested app that failed to work as intended. Candidates had made large contributions to the group, and that money essentially went to waste—to date, there is still debate over who should be the declared winner of the Iowa caucuses.

McFarland and Bhasin feel that this type of technology should not operate at a profit. Bhasin even suggests that this kind of basic campaign tool should be available to anyone for free and distributed exclusively by the government, rather than private companies. He points to Cambridge Analytica as an example of what happens when private interests and the right consultants can give campaigns massive advantages. Even Shadow, the disastrous Iowa app, was backed by the non-profit Acronym. While a nonprofit, Acronym has a Political Action Committee that has for-profit entities its non-profits can pay into. In the murky world of campaign finance, it can be hard to trace a consultant’s financial interests.

BerniePB, on the other hand, is free.

“We didn’t want BerniePB to be paid in any way, or monetizable,” says Bhasin. Indeed: it costs the two developers under $100 per month to keep the website running, a cost they are willing to eat if it means making the phone banking process more enjoyable for volunteers. They even maintain a much less active version of BerniePB called GrassrootsPB for down-ballot races and specific issues.

Plus, in a world where data is king, the only data BerniePB stores is the area code of the voter being called, which is converted into a zip code to make the live map function. And while their Chrome extension is not an essential campaign tool like a phone banking dialer might be, it still gives volunteers ownership over the time they contribute to the campaign—something McFarland feels is absent even in grassroots organizing.

“It motivates them to see it and feel like they’re part of something bigger,” said McFarland, whose concern is fostering repeat volunteers in a world where campaigns tend to churn through one-time volunteers quickly.

Without BerniePB, a call volunteer can’t see the total amount of calls they’ve made. Phone banking can be an emotionally intensive activity, especially when persuading voters or talking to angry opponents, and it can be difficult to see the impact of one’s calls during particularly demoralizing moments.

BerniePB allows users to be part of larger teams and see how their contributions add up when they work together. It would be difficult for one person to make 48,397 calls (which the top team on the leaderboard has done) but a group of 50 volunteers all working together can accomplish that kind of goal. To date, volunteers have tracked around 300,000 calls to potential voters. Though campaigns can track cumulative call totals within their own internal systems, a campaign volunteer normally would not be able to see this kind of information.

McFarland believes it would be beneficial to everyone involved if volunteers could build relationships with voters they’ve talked to, even if just for brief moments. As an example, he suggests that a volunteer might be utilized more effectively if they could make calls to their specific home town in a state, where they might be able to have deeper conversations with constituents (as of now, calls are usually made state-wide with no control given to volunteers over which areas get called).

“All of this data getting sucked into the campaign black hole which tends to pretty much just disappear after the election does not serve us well in building robust critically engaged networks that persist between election cycles and really constitute a movement,” McFarland argues, though he is aware that most people would prefer to have their data kept private.

He feels that despite social media and the internet making people feel more connected than ever, they have actually never been farther apart—because most people interact minimally in a meaningful way with others inside and outside of their own communities. A campaign must balance respect for data privacy with their desire to mobilize voters and create movements, which can be a fine line to walk.

Technology alone can’t address some of these aspects of political engagement. But, McFarland suggests, “it can certainly play a much more active role in abstracting away needless busy-work and providing people a platform to interact and collaborate.”

READ MORE: