Prison reform is very “in” right now. In addition to the 6,000 prisoners due to be released in the wake of changes to non-violent drug sentencing, the FCC ruled on Thursday to lower the cost of making outside phone calls for prisoners.

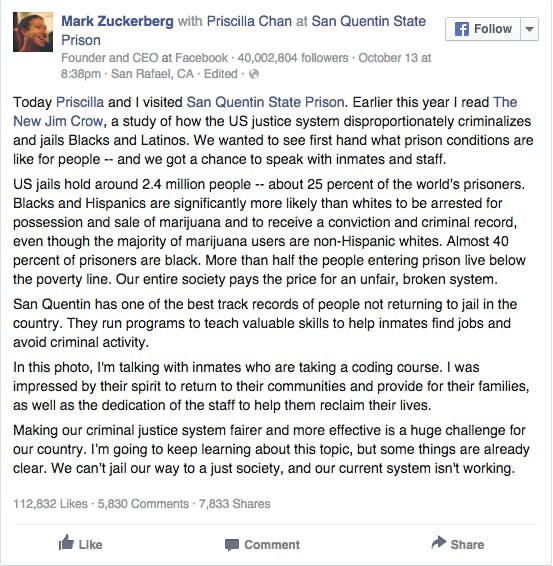

And for every hot-button issue in America, there’s someone waiting for a good photo-op—to make it seem like they ”get it.” On October 13, Mark Zuckerberg, the multi-billionaire founder of Facebook, visited the San Quentin prison. He and his wife, Priscilla, were making a special guest appearance at a class called Code.7370, which Entrepreneur described as “a program that teaches inmates computer coding skills four days a week, eight hours a day for six months.” Afterward, he wrote on Facebook, “Making our criminal justice system fairer and more effective is a huge challenge for our country. … We can’t jail our way to a just society, and our current system isn’t working.”

The trouble is that it’s one thing to be critical of what is now referred to as “mass incarceration” but quite another to demonstrate a politics that actually works to dismantle the prison-industrial complex. It’s time to put pressure on those in power to go further than hollow “mass incarceration” rhetoric, and stop approaching the topic like it’s the latest political fad.

In his Facebook post, note that Zuckerberg is not calling for an end to mass incarceration itself. Instead, he talks about making the prison system “efficient” and, presumably, more profitable. Given that he’s the CEO of one of the largest tech companies in the world, it’s natural to assume his plan would link the teaching of “skills” to a business tie-in with Facebook in prisons. Ironically, the men in the class he visited learn their skills with no Internet access, using a proprietary programming platform “that simulates a live coding experience.”

But even when there’s Internet available within prisons, there’s little-to-no regard for the rights of the incarcerated while they access the resource, a problem Facebook reportedly enables through its work with law enforcement.

In February, Motherboard’s Jordan Pearson reported that in South Carolina, Facebook collaborates with authorities to crack down on inmates using the platform. And what’s more, according to the report, both bodies also work “to stop average, non-incarcerated people from helping inmates communicate with the outside,” in the event that a friend or relative posts on their behalf.

After examining public records during an independent investigation, the Electronic Frontier Foundation—a nonprofit that defends civil liberties on the Internet—found:

[O]ver the last three years, prison officials have brought more than 400 disciplinary cases for “social networking”—almost always for using Facebook. The offenses come with heavy penalties, such as years in solitary confinement and deprivation of virtually all privileges, including visitation and telephone access. In 16 cases, inmates were sentenced to more than a decade in what’s called disciplinary detention, with at least one inmate receiving more than 37 years in isolation.

Yes, inmates face the threat of decades of solitary confinement, simply for using social media. The application of the policy is so extreme, as EFF noted, that corrections officers often must suspend solitary confinement due to lack of space. But how does Facebook, the corporation, have any responsibility in this?

Zuckerberg can and should be criticized for failing to grasp that making the system more “efficient” and creating a subsidiary class of semi-professionals doesn’t solve the root of the issue.

According to EFF, Facebook—at the behest of the South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC)—suspends profiles for reported violations, which include using aliases or sharing passwords with third parties, such as relatives on the outside. But the platform went one step further: Documents obtained by EFF showed Facebook may have taken down profiles when there were no allegations that inmates violated prison policies or the site’s terms of service. Instead, as the EFF noted, “The prisons simply asked to have the profiles taken down because they belonged to incarcerated people.”

Following public backlash, Facebook eventually changed its policies. Among other things, the company now requires prisons to include links to “applicable law or legal authority regarding inmate social media access.” But Facebook’s default policy defers to requests that amount to blanket forms of censorship by the SCDC. And even now, as EFF notes, Facebook won’t reveal statistics about the number of inmate takedown requests.

Although Zuckerberg cannot be blamed entirely for such structural problems, he can (and should) be criticized for failing to grasp that making the system more “efficient” and creating a subsidiary class of semi-professionals doesn’t solve the root of the issue. Instead, the CEO should use his platform and public voice to 1) not collude with prison officials in censorship and 2) demand that Internet access be a basic right.

Harvard’s debate team lost to a group of super-smart prison inmates who don’t even have access to the Internet: http://t.co/IAeHYjnCv6

— Lauren O’Neil (@laurenonline) October 8, 2015

But this is hardly the first time that Zuckerberg has stepped into a project that claimed altruistic intentions but failed to help the truly disadvantaged.

In 2010, Mark Zuckerberg made a $100 million gift to reform Newark’s ailing school system, which is overwhelmingly African-American, working with then-Mayor Cory Booker and Gov. Chris Christie (R-N.J.). But that reform was not a success. As Democracy Now points out, “neighborhood schooling was replaced with a lottery system that divided families and forced children into dangerous commutes.” Even further, charter schools expanded, policies shifted to overemphasize test scores, and the system’s overall performance dropped.

According to Dale Russakoff, author of The Prize, a book about the debacle, Zuckerberg, Booker, and Christie all decided that the best way to bring about the “reform” they envisioned—about which Zuckerberg had done little research—was to bypass the groups who actually knew what was needed, including students’ parents. In fact, Newark residents first heard of the new reform initiative not through official channels but on the Oprah show, where the three men made their grand announcement, to much oohing and ahhing from Winfrey herself.

This particular collaboration between the government and the private sector didn’t prove beneficial for aiding underserved communities but rather ignored their expressed needs in favor of a self-serving agenda. That Zuckerberg replicates what’s perhaps a deceptively benevolent approach—as it pertains to Facebook and Internet access within prisons—shows he’s most interested in addressing rights violations from “mass incarceration” if he gets good press from it.

Yet Zuckerberg is not the only one with a potentially ham-fisted approach to “solving” the problem of prisons. His visit to San Quentin came in the midst of several other public statements against mass incarceration, ironically made by the same people who work so hard to keep the PIC in place. For example, much is being made of a coalition of 130 law enforcement officers—calling themselves the Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration—coming out with a collective policy to push for alternatives to incarceration.

So much about the background and context of the group should raise eyebrows and not elevate any hope for a sustainable solution. The outfit’s co-chairman is the Chicago police superintendent, Garry F. McCarthy. Chicago, home of Jon Burge, the police chief who tortured hundreds of men into confession, is also the home of Homan Square, the secret prison further exposed in recent dispatches from the Guardian. As the reports highlight, more than 7,000 people have been disappeared from Homan Square, cut off from access to lawyers and friends and family.

Additionally, the city is notorious for its high levels of police misconduct and brutality.

In that sense, Zuckerberg seems like a drop in the bucket when it comes the problem. But he is the only one with, literally, billions to throw around. Even if one argues that it’s ultimately men like McCarthy and organizations like SCDC that cause actual, bodily harm to prisoners, Zuckerberg’s actions cannot be absolved. Rather, Zuckerberg’s power and influence provides expensive cover for the brutality that the prison-industrial complex inflicts upon its inhabitants—both the disappeared and those inside prison—made invisible by the twin apparatuses of denial and deceit.

If we are serious about ending mass incarceration, we need to go beyond buzzwords borrowed from Michelle Alexander and her book, The New Jim Crow. We have to recognize that the words and actions of Zuckerberg, McCarthy, and their counterparts will never amount to any real change beyond petty reforms. Instead of giving them so much public attention, we might begin to pay attention to the hard and often dangerous work being done on the ground by local, grassroots organizations—like the activists who recently protested a conference of police chiefs in Chicago or the work done by those who finally won reparations for those tortured by Jon Burge.

Yasmin Nair is a freelance writer, activist, academic, and commentator, the co-founder of the radical queer editorial collective Against Equality, and a member of the Chicago-based group Gender JUST. Follow her on Twitter.

Illustration by Max Fleishman