Much has been written about Dune’s Islamic and Middle Eastern background. In the Washington Post, Haris Durrani describes Frank Herbert’s Dune novels as “thoroughly Muslim,” treading a line between homage and cultural appropriation. The books borrow vocabulary from Arabic, and as Roxana Hadadi points out in Vulture, the Fremen (the indigenous population of Arrakis) were partly inspired by the Bedouin people of the Arabian Peninsula. Yet Denis Villeneuve’s Dune tries to dilute and downplay these influences, with mixed results.

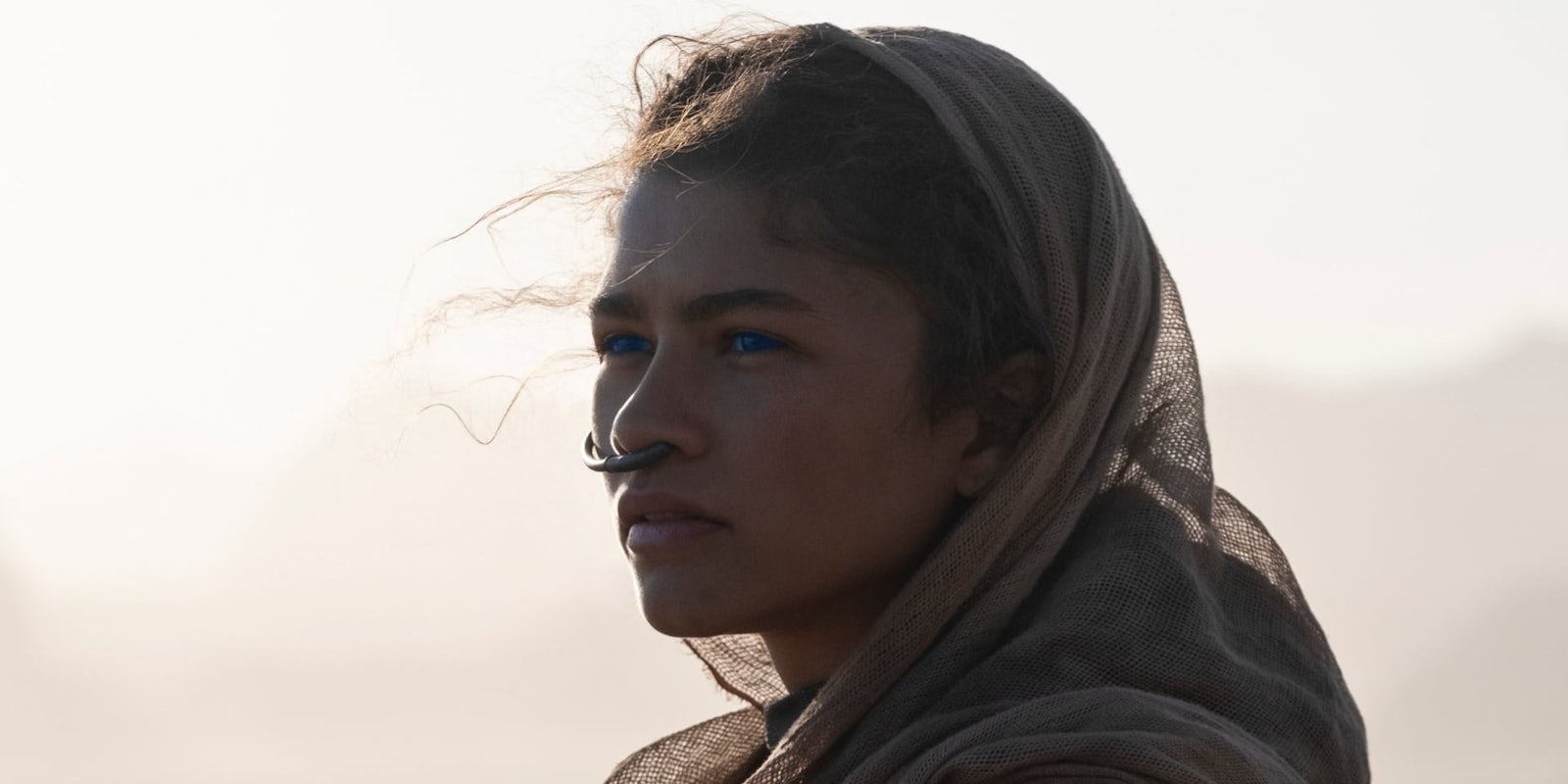

Long before the film came out, Villeneuve faced criticism for failing to include MENA (Middle Eastern and North African) actors in the main cast. In the final product, this plays into a more pervasive sense of cultural erasure. Dune is still unmistakably about colonialism, easily interpreted as an allegory for oil wars in the Middle East. We hear snippets of Arabic in the script, and the Fremen costumes take inspiration from Bedouin and Tuareg clothing. Arrakis was filmed on location in Jordan. But the film removes these details from their real-world origins, rendering Dune‘s MENA elements oddly nonspecific.

Hans Zimmer’s score is an interesting example; a characteristically epic work from one of Hollywood’s biggest composers, hinging on Middle Eastern influences that Zimmer seemingly doesn’t want to acknowledge.

The musical landscape of Dune

Zimmer’s Dune music is deeply rooted in the sci-fi setting, creating a rich soundscape of synth noises, industrial percussion, and female vocals. Singing in a fictional language, these voices represent the all-female Bene Gesserit order. Sighs and hums merge into the desert wind, and drums overlap with the rhythmic throb of ornithopter blades. It’s a different strategy to the music in something like Star Wars, where a symphony orchestra evokes certain characters and emotions, reflecting the work of European composers like Holst and Dvorak. There’s no sense of that orchestra existing “inside” the world of Star Wars. Meanwhile, Dune blurs the line between sound effects and score, and on two occasions the music is performed on-screen.

The Atreides family, our point-of-view characters, hail from Caladan. It’s a planet with a Scottish-sounding name (“Caledonia”), and a Scottish-looking landscape. They arrive on Arrakis accompanied by bagpipes: Scotland’s most iconic instrument, and a familiar image for the British military. In Villeneuve’s words, those bagpipes elicit “a blaze of colonial pageantry.”

With their aristocratic costumes and American accents, the Atreides leaders are coded as Western colonizers. Their enemies the Harkonnens are more abstract, as are the unseen Emperor’s army, the Sardaukar. They star in Dune’s other big music scene, where Tuvan throat-singing accompanies an act of mass blood sacrifice. The film separates this resonant vocal technique from its Mongolian origins—chosen, perhaps, because it will simply sound “foreign” to Western ears.

In a score that largely avoids memorable melodies, there’s one other familiar element: The Middle Eastern motifs used for Arrakis and the Fremen. We have the haunting solo vocals from Loire Cotler (an American singer who fuses Jewish, Middle Eastern, and South Indian vocal traditions), along with a recurring drum rhythm, and a lilting melody played on the Armenian duduk.

How Dune‘s music evokes the Middle East

The duduk is a Hollywood mainstay, frequently used for sci-fi/fantasy projects like Game of Thrones, and films set in the Middle East. Hans Zimmer has used it several times beginning with Gladiator, where he wanted to create a “dirty, tribal, gritty” sound for the film’s Moroccan sequences. To learn more about the duduk’s cinematic popularity, I spoke with Omar Fadel, a composer who grew up in Texas and Dubai, and has worked on a wide array of projects ranging from Assassin’s Creed to PBS documentaries.

“The use of ethnic instruments reminded me of Black Hawk Down and some of those scores of [Hans Zimmer’s] from the early 2000s,” says Fadel, after listening to the Dune score. “You’ve got the wailing, Persian/Iranian-style vocals, and you’ve got the duduk.”

While praising Zimmer’s Dune music overall, (“It’s done at the highest level”) Fadel is fondly amused by the duduk’s Hollywood reputation. He characterizes the instrument as a kind of auditory shorthand for “ethnic instrumentation” and Middle Eastern settings. “It’s funny. I never, prior to 2003 maybe, even heard of the duduk.” But after the start of the Iraq war, suddenly “anything ethnic, there’s like a duduk with a bunch of reverb on it.” Fadel has now used the duduk on several projects himself, employing its soulful sound on a fantasy show earlier this year. “I look at it from the nonspecific ethnic category,” he explains. “Someone who’s an Armenian music purist might disagree with me, but I by and large am not a traditionalist.”

The duduk’s Hollywood legacy is an interesting fit for Dune’s culturally nonspecific setting. Villeneuve depicts the Fremen as a multiracial culture with hints of North Africa and the Middle East. However, he emphatically doesn’t cast any MENA actors to acknowledge the Islamic, Bedouin, and Algerian roots of the novel. Similarly, the duduk offers a vague-but-recognizable Middle Eastern atmosphere, without being directly identifiable.

In an email to the Daily Dot, ethnomusicologist Michael Frishkopf (Music and Media in the Arab World) explained that Dune’s duduk and bold solo vocals “invoke the Middle East or possibly India through the use of non-western scales.” Zimmer uses harmonic minor intervals and augmented seconds for the Arrakis motifs, which Frishkopf describes as Hollywood’s “stereotypical melodic formula” for “exotic” scenarios.

“Hollywood composers use stereotypes either because they don’t know better, or because they know what audiences will respond to,” says Frishkopf, highlighting the cliché of “an evil Arab terrorist whose presence on-screen is always accompanied by a duduk sound playing an augmented 2nd.” He also compares the Arrakis vocals to North African Berber folk music. Interestingly, Zimmer and singer Loire Cotler don’t cite any specific MENA references in interviews. Cotler told the New York Times that her Dune vocals are a hybrid of “far-flung influences” including South Indian vocal percussion, jazz saxophone, and Celtic laments, adding, “It’s a vocal technique called ‘Hans Zimmer.’”

Villeneuve’s Dune is a stunning work of sci-fi cinema, and its creative team is keen to emphasize the scope of its futuristic alien setting. But “alien” to whom? As Roxana Hadadi mentions in Vulture, the film offers subtitles for the sign language and Mandarin spoken by the Atreides characters, and for the fictional Sardaukar language. Meanwhile, the Fremen dialogue remains untranslated, leaving fans to point out on TikTok that some words are literally Arabic. Something similar happens with the music, where much of the film has an atmospheric techno backdrop, while Arrakis receives a recognizably Middle Eastern theme.

While this isn’t one of Zimmer’s orchestral scores, Dune echoes a long tradition for orientalism in Western classical music. From Mozart to Tchaikovsky, numerous European composers have imitated musical styles from Turkey, China, India, and the Middle East. This carried over to Hollywood, with the scores for films like Aladdin and Lawrence of Arabia. Even in The Lord of the Rings, composer Howard Shore takes a brief break from his European influences to introduce Sauron and Mordor. The films’ evil foreign invaders are heralded by the rhaita, a North African woodwind instrument.

Hans Zimmer—a longtime fan of the Dune novels—hasn’t really spoken about the film’s Middle Eastern inspiration. During promotional interviews, he focuses instead on the thematic importance of female singers, the complexity of his synth score, and his team’s experiments with building new instruments out of scrap metal. Like the awe-inspiring production design and complex worldbuilding, Zimmer’s music offers fans plenty to chew on. But it feels telling that Zimmer, just like Villeneuve and his co-writers, tries to steer clear of certain topics while discussing the film.