“We’re building a community.”

This was the refrain I heard again and again as I spent the day with Occupy ICE LA, the group that has been camped in front of the Los Angeles Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices since June 23, demanding the abolition of the agency that has targeted and detained immigrants—and even citizens—for deportation.

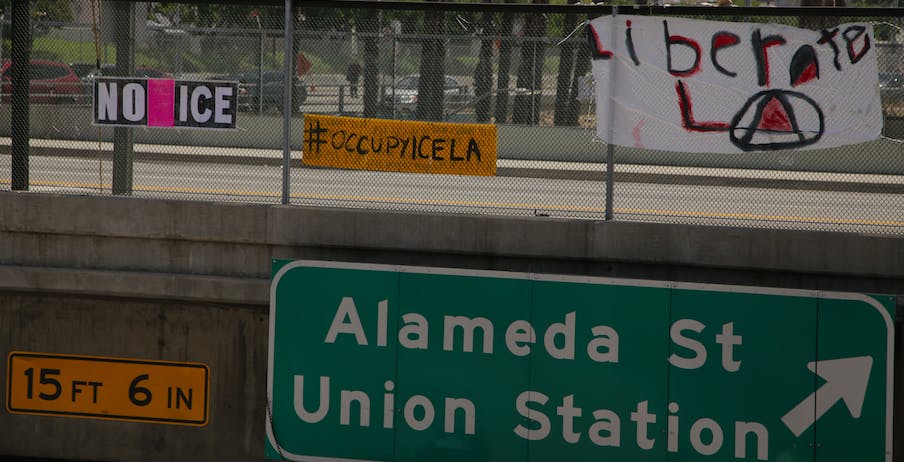

This coalition of activists, comprised of a variety of citywide organizations, has held an encampment with a consistent core of 15 to 20 people, along with several dozen more who spend time and donate supplies when they can. Their tents stretch the length of the city block in front of the massive federal building at 300 N. Los Angeles St.; across the street, they have decorated the highway overpass with posters and banners created by the protesters bearing sentiments like “No one is illegal on stolen land” and “Stop tearing families apart.”

Their demands are simple if ambitious: Shut down the Metropolitan Detention Center, have ICE stop all its work in L.A. County, and abolish ICE as a whole. More broadly, they see their protests as a critique of U.S. imperialism and the prison industrial complex.

If you’ve been looking at the news coming out of the various Occupy ICE movements around the country, you probably wouldn’t expect the level of optimism on display at the corner Aliso and Alameda streets, where musical guests and teach-ins are a common sight. The blockade of ICE offices in Portland—the first of its kind in the nation—was forcibly disrupted by riot police on June 29. In Philadelphia, bike cops trashed an Occupy ICE encampment last week in what local journalists called a “bike-dozing.”

Regardless, a number of other Occupy ICE actions continue throughout the country, including in New York, Detroit, San Diego, Louisville, and Wichita. While the groups in different cities aren’t necessarily in constant communication, they are often supporting each other and sharing information on social media. Most have also encountered some form of law enforcement interference or disruption. Occupy ICE LA is no different.

At the L.A. site, security guards linger throughout the day, clearly looking for an excuse to put pressure on the protesters. In the morning, they complain that the camp is blocking the sidewalk. In the afternoon, they demand that the activists clear the lawn. One protestor, a tall young man with long brown hair named Nobu, is working on a poster board that outlines the encampment rules and priorities as a security guard approaches.

“Can’t have that on government property,” the guard says, flanked by two co-workers. Each of them outweighs Nobu by at least 70 pounds.

“This land doesn’t belong to any government,” Nobu responds as he shuffles off the lawn.

The guard calls a code into an intercom system, and within minutes, about a half-dozen security guards, a handful LAPD officers, and a couple plainclothes ICE and Department of Homeland Security agents are on the scene.

Things don’t escalate from there; Nobu picks the sign up off of the grass. But the message being sent by the powers that be is clear: If they wanted to, they could make this look just like Portland or Philadelphia.

The protesters at L.A.’s ICE offices don’t expect their occupation to be easy, and they don’t expect the encampment to last forever. The core group is largely comprised of veterans of other movements: ICE Out of LA, the California Immigrant Youth Justice Alliance, Black Lives Matter, Ground Game LA, Democratic Socialists of America, About Face, National Day Laborers Organizing Network (NDLON), and People Organized for Westside Renewal (POWER). Nobu, along with his comrades Cyrus, Amari, and Yohualli, spent months protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline Protests at Standing Rock. They stood alongside the water protectors, building structures and providing security for elders. To them, this protest is an extension of that movement: a fight against what they see as an American imperialist legacy of separating Black and Brown children from their families and communities.

Yohualli, who also has long brown hair but sports a beard to match, says he never thought they could stop the Dakota Access Pipeline from being completed—“We were building something bigger than ourselves”—and he isn’t idealistic enough to believe that this action will lead to the immediate abolition of ICE, either. “This is a movement,” he said. “And there will be other struggles.”

Carter Moon, an activist with hyperlocal group Ground Game LA, says the protestors have learned a lot from some of the more experienced activists. “A lot of the people who have been most directly involved here were actively involved in Occupy Wall Street and Standing Rock,” he said. “They know how to keep the camp feeling open and democratic and in control for anyone who wants to participate.”

To get more people involved, the group planned a larger civil disobedience action on July 2, in which activists blocked the entrances and driveways at the ICE facility, fully aware they were risking arrest. In the end, 18 protestors were arrested. “We had a lot of support from a lot of different communities,” John Motter, a veterans and homeless rights activist, told the Daily Dot, rattling off appearances by faith leaders, indigenous people, and City Councilmember Mike Bonin, who represents nearly 300,000 people in his district. “And all willing to put it on the line and stand up for undocumented people.”

With the encampment near L.A.’s Skid Row neighborhood, some of those who have joined the group include the unhoused, recently released from jail, or immigrants themselves. “Living on the street is a reality for so many Angelenos and houseless folks everywhere, especially for those impacted by ICE,” Sarah L., an organizer staying at the camp told the Daily Dot, “and connecting on a new and more human level has helped me check my privilege and improve the ways I can help others.”

Francisco, a man who has been camping with the group for over a week, is himself an immigrant who has gone through the asylum process. As a precaution, he sleeps with his immigration papers next to him in a plastic case, should ICE roust him from his tent. “It affected me, you know, “ he told the Daily Dot. “So, I needed to be here to try and do something about it.”

As the protest wears on, the encampment has focused on building solidarity with other groups in Los Angeles. The groups conduct daily teach-ins with guests leading discussions on topics not necessarily ICE- or immigration-related; when I was there, representatives from Southwest Asian North Afrikan LA (SWANA) were discussing Palestinian liberation.

Motter emphasized the value of education to the movement. “We and other folks around the country are bringing attention to this issue,” he said. “We’re educating people on what ICE does. We’re talking about what abolishing ICE means and why it’s necessary. We want to mainstream the idea. Have it be the purity test for Democrats at least.”

The group understands that their demands may not be met tomorrow, and ICE will certainly outlive their encampment. What they are betting on is that ICE won’t outlive their movement and the community they’ve built. In the short term, the group is using social media, podcasting, and streaming to get their message out, as well as events like the “Decolonization Block Party” it hosted on July 7. They post immediate needs @occupyicela on Twitter and are always looking for assistance with warm meals and for comrades to join them. For those who do want to stay the night, the group makes sure they have a tent to sleep in.

“The encampment is a way of holding space,” the coalition wrote in a statement to the Daily Dot. “We ask everyone who supports us to come down and camp if they can and abide by/contribute to our community agreement. We are safer in large numbers.”

For now, at least, the occupation continues. What the movement looks like in the long-term, however, still remains to be seen.

Disclosure: Brenden Gallagher has worked with some of the activists interviewed in an organizing capacity before around other political issues in Los Angeles. He is not, however, a member of ICE Out of LA or Boycott ICE LA.