It started out as a prank—and maybe that’s all it ever was.

Comedy writer Zach Heltzel, a friend of mine, told me about a new feature he discovered on the Twitter platform SocialBro. It allows you to generate a list of active Twitter accounts that contain a particular keyword in their profiles, and with just a few clicks, you can mass-add them to a Twitter list. If the Twitter list is public, Twitter automatically notifies all of these users of the name of the list and the fact that they have been added—the perfect recipe for digital mischief.

Zach mainly used it for harmless fun, like adding 5,000 people with “Harry Potter” in their profile to a list called “It’s leviOsa not levioSA,” and adding 5,000 people with “Disney” in their profile to a list called “The Mickey Mouse Club.” But he stumbled onto a landmine when he decided to add people with “feminism” in their profile to a list called “Robin Thicke fans”: a somewhat sensitive point, since Robin Thicke recently had joked about what a pleasure it is to degrade women.

“I’m kind of freaking out. [It] is causing a fucking uproar,” Zach confided to me. I asked him what he expected to happen, and he said he wasn’t sure. But he didn’t expect massive organized campaigns to report him to Twitter and try to get him banned. After hours of insults and threats, he backpedaled quickly and ended up deleting the list.

This piqued my curiosity. Most people I know, including myself, have been added to lists with insulting names, or descriptions that were factually false. Being an outspoken left-winger, I’m used to being labelled with the standard “insulting” labels that conservatives use against liberals.

It never made me angry, and I never thought to try to get someone banned over it. But Zach’s prank with his “Robin Thicke fans” list made me wonder: What would happen if you put people into lists with labels that are the political opposite of how the identify themselves in their bios?

It seemed to be worth an investigation, and this is what happened.

Day 1: Conservatives

At about 10am, I used SocialBro to create one list called “Muslims” and populate it with approximately 500 people who have “Tea Party” in their Twitter profile description. I also created a list called “Abortion Advocates,” which I populated with about 500 people who have “#tcot” (a popular hashtag used by politically active conservatives on Twitter) in their profile.

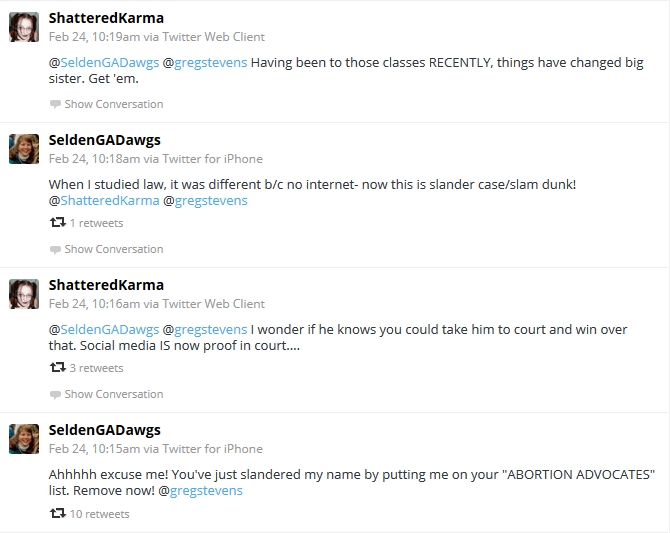

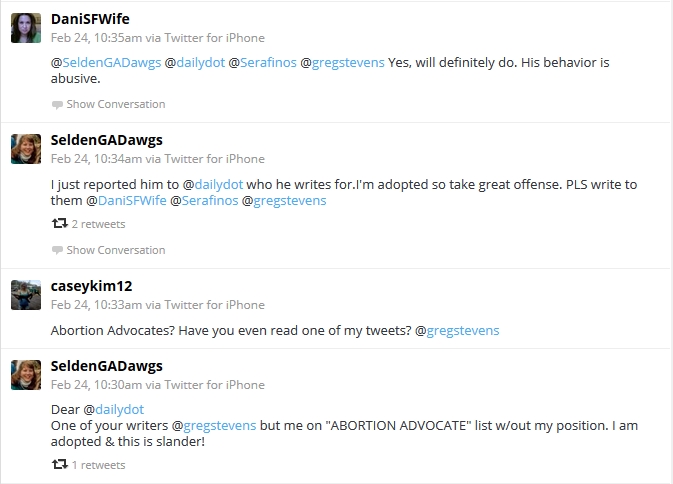

Almost immediately, the most active users on the list noticed and began to react. I was accused of slander and told I could be taken to court.

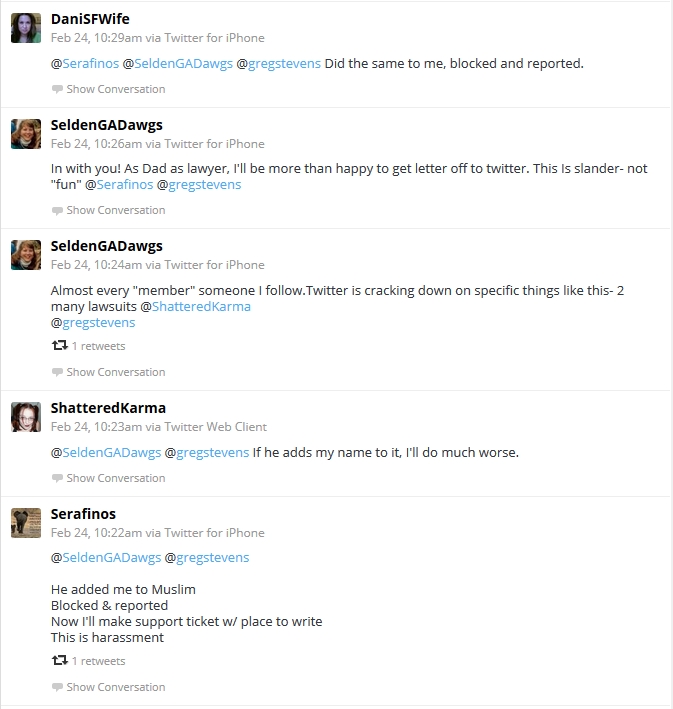

People also said they would report me to Twitter for harassment.

Many of the tweets came from one or two people who were actively attempting to “rally” people against me: tweeting to the Daily Dot to report my “abusive” behavior, reporting me to Twitter, and encouraging others to do the same.

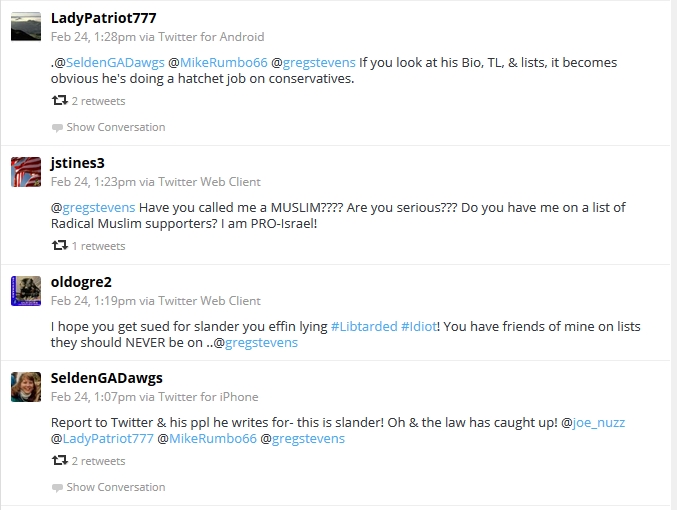

As the afternoon wore on, the language became more severe. Apparently, my lists constituted doing a “hatchet job” on conservatives.

There were three people, over the course of the day, who did nothing more than politely tweet me and ask the be removed from the list. When that happened, I always complied; however, I did not offer any explanation.

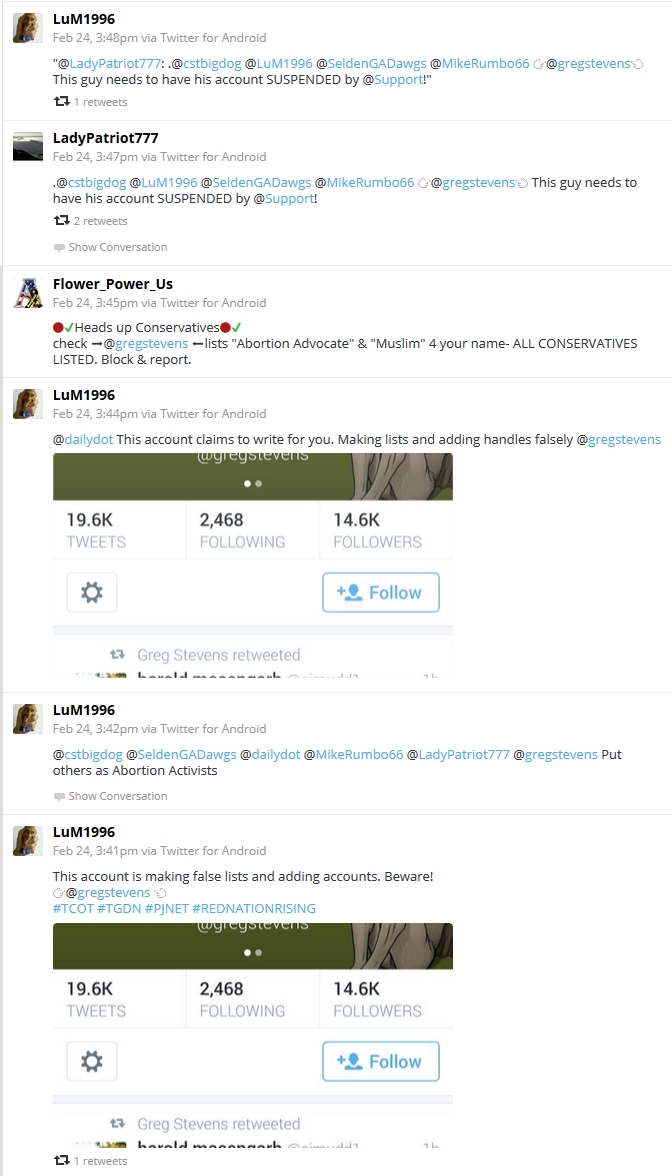

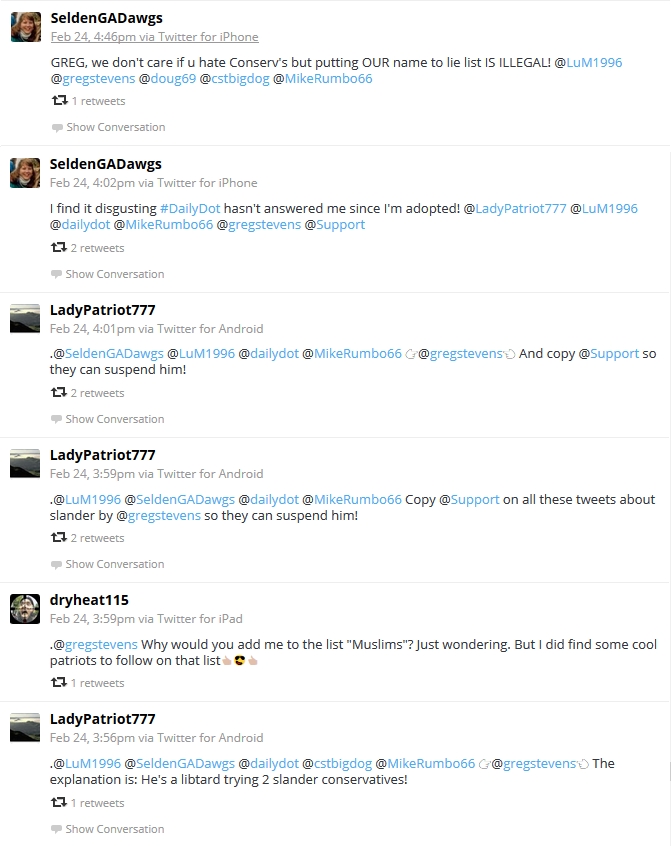

By late afternoon, a small handful of leaders emerged who were persistently pushing a campaign to notify the world about me and have people report me.

For those of you not familiar with the details of how Twitter works: When people put a single character, such as a period or quote mark, before @username of the people they are talking to, it allows anyone who follows that person to see it, further publicizing the conversation. The goal of these tweets was not merely to discuss the terrible thing I had done, but to make sure as many people as possible knew about it.

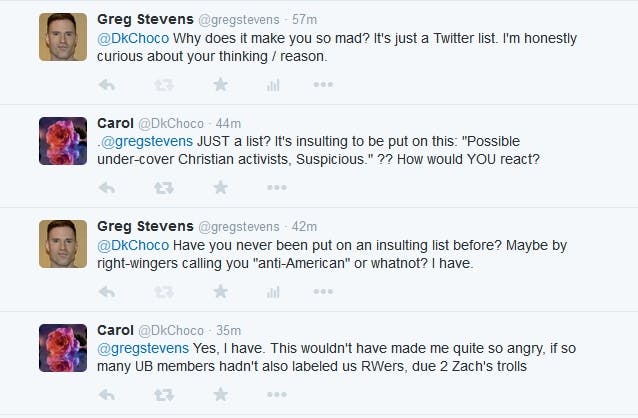

After a while, when it looked like it would never let up, I reached out to one or two of the leaders to communicate with them. They were still very mad, but my attempts to reach out calmed the waters somewhat. Eventually, one person even conceded that adding someone to a Twitter list called “Muslims” is not, in fact, illegal.

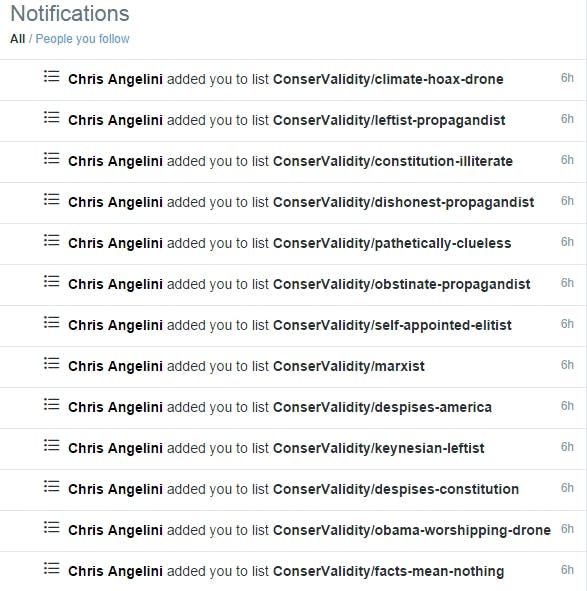

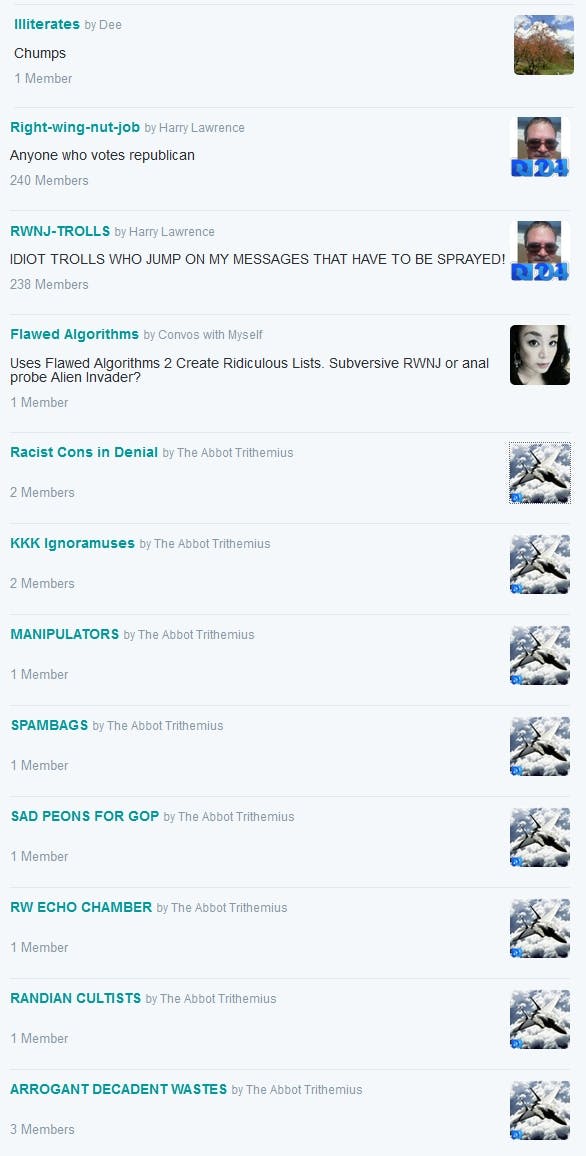

A number of the conservatives added me to their own lists in retaliation, as well. In many cases, I’m the only person (as of this writing) on the list, indicating that it was created specifically for me. The names of those lists speak for themselves.

All in all, it was an exhausting day. I was never actually worried about my account being suspended or about being sued, but getting yelled at all day was tiring. I drank some juice and went to bed early to be ready for the second day of the project.

Day 2: Liberals

The following morning, I used SocialBro to create one list called “Religious Right” and populate it with approximately 500 people who have “#UniteBlue” (a popular hashtag used by politically active liberals on Twitter) in their Twitter profile description and another list called “I love the Koch brothers,” which I populated with about 500 people who have “progressive” in their profile.

Just as on the previous day, the most active Twitter users noticed the lists they were added to and responded immediately. The quality of their responses were different, though. Liberals seemed less angry; more were simply confused.

The morning went by with no accusations of harassment and no threats of legal action. That is not to say that nobody’s feathers were ruffled. One person whom I follow, who ended up being caught up in the “Religious Right” list purely by chance, sent me a Direct Message and said that it made her angry. When I let her know privately that it was simply a project to see how people reacted, she replied: “Well, I was upset. I didn’t appreciate it.”

But through most of the morning, even the few “public shaming” tweets sent by liberals came across as more amused and perplexed than angry:

By early afternoon, however, tempers became hotter. A very vocal critic emerged who repeatedly tweeted announcements about my bad behavior, to make other people aware of what a “jerk” I was for adding her and other lefties to the “Religious Right” list.

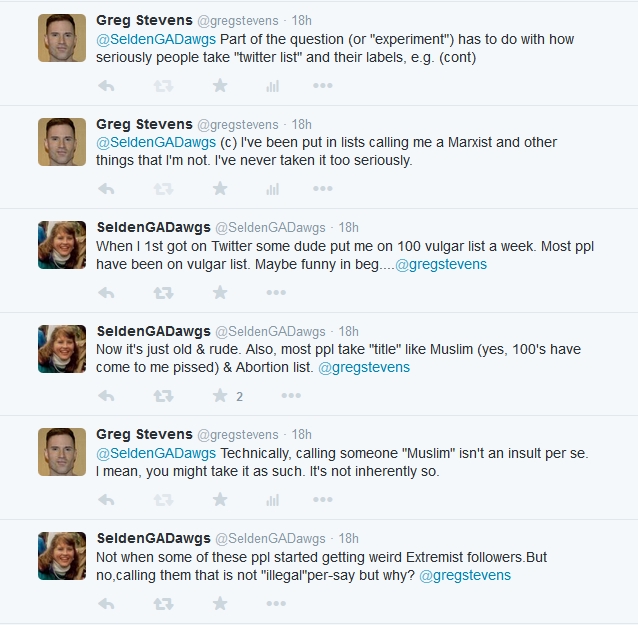

Because I had engaged my most vocal conservative critics the previous day, I reached out to this woman as well and asked why she found it so upsetting simply to be put on a Twitter list.

After that, some of the anger subsided and tweets from angry and perplexed liberals eventually trickled to a stop. Throughout the entire day, there were no threatened lawsuits. Nobody tried to start an organized campaign to contact the Daily Dot or Twitter Support to have me reprimanded or banned. Nobody talked about their father being a lawyer and suing me for slander.

Some liberals did also create “retaliation lists” for me, although, again, the character of the names chosen by the liberals to insult me were very different from the retaliation lists created by conservatives.

It is important to bear in mind that, of course, none of this is scientific. We should be careful about drawing broad conclusions from this little project. For one thing, I’m blatantly liberal on my own timeline, and by a coincidence many of the people who got caught up in “Religious Right” and “I love the Koch brothers” lists were followers of mine. This could have been part of why many of them reacted with confusion rather than anger.

But even from this small sampling, the broad pattern is clear and interesting: When liberals were identified as a group that they dislike (Religious Right), they reacted with confusion and annoyance; when conservatives were misidentified in the same manner (Muslims), they reacted with insults and threats. Moreover, the fact that conservatives appeared quicker to anger is not inconsistent with the scientific data that is available.

A number of neurological studies have shown that conservatives tend to respond more strongly to fear and anxiety, they react more instinctively and viscerally to things they don’t like, and people who are more fearful gravitate toward conservatism. Differences in the general underlying personalities of conservatives and liberals and differences even in their basic brain chemistry are certainly not the sole explanation for the differences I saw on Twitter—but it is striking how consistent the behavior is with the theories that are out there about differences between the two ends of our political spectrum.

A third result

There was one more thing that I learned from this entire project: I just don’t have a taste for trolling. In essence that is what this kind of prank is, and it doesn’t matter whether I was doing it for an article or not. It was being irritating simply for the sake of being irritating: otherwise known as “trolling,” a pastime that many people seem to enjoy and that some people can’t get get enough of.

During this project I got to see what it was like to troll both my political adversaries, conservatives, and my own people, liberals. It may have been slightly easier, emotionally, for me to play the prank on conservatives because they are “the other side,” but in all honestly, it still left me cold. I didn’t feel exhilarated or proud. Maybe I should have. Maybe that would have been natural. I’m not claiming any deep insight into the psychology of trolling. I’ve only learned that trolling isn’t for me.

Illustration by Jason Reed