The Internet lets you talk to people from all over the world. A teenager from Brazil and a neuroscientist from Beijing can chat in real time. A cam girl from Dallas can entertain a great-grandpa in Brussels. Services like Google Translate help break down formerly hard-to-get-around communication barriers, offering an imperfect but undeniably practical and free translation service. Log onto Facebook, and your foreign friends’ posts will get translated by Bing. If you want to say “Nice to meet you” in a different language, it only takes a quick Google search to pull up the phrase. Or you can use a Gchat translation bot to figure out someone’s native greeting in a few seconds while you’re instant messaging them.

Skype just debuted a remarkable new feature it’s readying that will automatically translate voice calls conducted by people who speak different languages, essentially bringing the science fiction trope of a universal language translator to reality (of course, with a more limited, less intergalactic language list). And Google is planning its own automated translator. “The goal is to become that ultimate Star Trek computer,” Google senior communications associate Roya Soleimani told California Report. Google’s recent purchase of WordLens, an app capable of automatically translating text, suggests the team is fast-tracking its plans to become to go-to online translation company… and WordLens, which uses a smartphone camera to take pictures of signs and other writing, already has an app ready for Google Glass, underlining that the company sees a future where their headwear doubles as an automatic translator, changing how people travel and redefining “foreign.” Even people who hate the idea of strapping Glass to their faces have to admit how real-time, mobile translation would be a benefit.

And this futuristic, barrierless society is all part of Luis von Ahn’s vision—though the programs and algorithms are just a rough draft.

Von Ahn is a pioneer of polyglot culture: In addition to working as a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon, he’s a MacArthur Fellow who sold his reCAPTCHA verification company to Google, and the founder of Duolingo, an online language platform with grand ambitions to translate the Internet. At a TED Talk, von Ahn stressed his desire to use Duolingo to create an Internet accessible to everyone, not just English speakers.

Duolingo offers a renowned language-learning program, and the company wants to use crowdsourcing to translate the Internet. Organizations like Buzzfeed and CNN pay Duolingo to translate their international sites, which allows the company to keep its language services free.

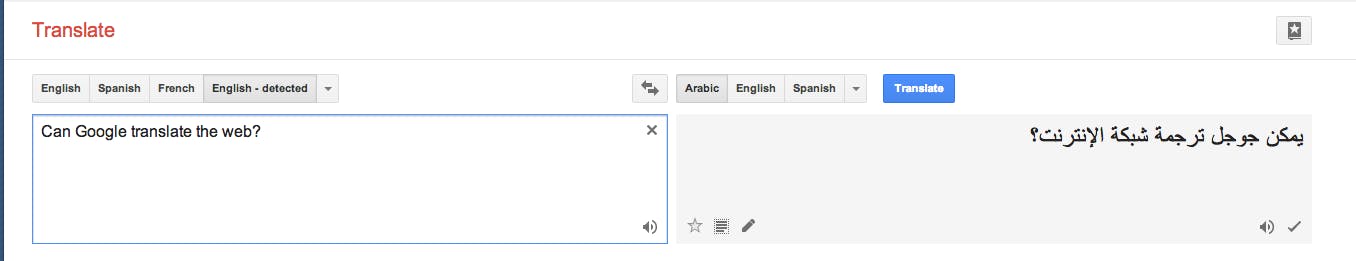

Duolingo’s crowdsourcing model is far from unique, though the scope of its mission is vast. Other companies, like Microsoft and Google, have just as lofty goals, but are eschewing Duolingo’s crowdsourcing strategy in favor of algorithms. Google Translate has improved significantly in recent years, which the team credits to its “statistical machine translation.” Its model works for over 80 languages, from Hmong to Hungarian.

“When Google Translate generates a translation, it looks for patterns in hundreds of millions of documents to help decide on the best translation for you. By detecting patterns in documents that have already been translated by human translators, Google Translate can make intelligent guesses as to what an appropriate translation should be” the Google Translate blog explains.

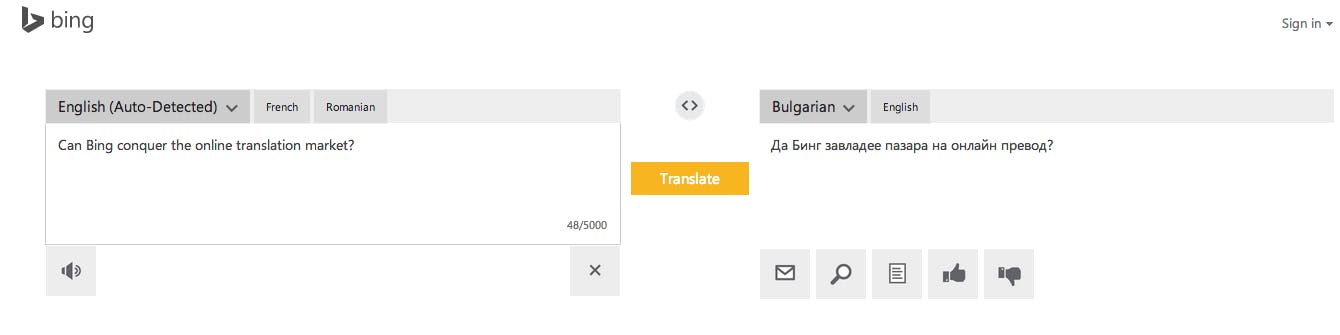

Bing uses an algorithm as well. That doesn’t mean Microsoft and Google leave translation entirely up to machines. The companies ask users to rate the quality of the translations, and actively seek user-generated improvements. And they’re not the only companies using crowd insight to aid their translation. While Facebook has a partnership with Bing to provide automatic translations for user-generated content, the company still relies heavily on volunteer communities to translate its website into the hundreds of languages of its users.

Though the advances in online translation made by Duolingo, Google, Skype, and other companies is promising, myriad roadblocks remain. While von Ahn envisions a digital world without language barriers, because of Duolingo’s userbase, it primarily translates articles and documents from English into other languages, creating a system where English content is exported to other languages to a disproportionate degree.

Both crowdsourced and automated or data-driven translation services have a fatal flaw: They’re not completely accurate (and in the case of Google Translate, Bing’s translation service, and all of those smaller online translators you used to fudge your French homework, they’re sometimes horribly inaccurate). When it comes to casual conversation, or getting the gist of what someone is saying, that’s fine. But these services can’t supplant analog professional translation for documents and articles that require more finesse to fully articulate, and they’ll need to make drastic improvements before they attempt to do so. Von Ahn admitted as much about computer-generated translations.

“Now some of you may say, why can’t we use computers to translate? Why can’t we use machine translation? Machine translation nowadays is starting to translate some sentences here and there. Why can’t we use it to translate the whole Web? Well the problem with that is that it’s not yet good enough, and it probably won’t be for the next 15 to 20 years. It makes a lot of mistakes. Even when it doesn’t make a mistake, since it makes so many mistakes, you don’t know whether to trust it or not,” he said.

His vision of a Web translated by humans is equally out of reach because, well, it’s going to take a very long time for humans to do all that translating (not to mention that new content gets posted in vast volumes every day).

Languages never evenly match up and there will always be a modicum of sentiment or emphasis lost in the transition from one tongue to another, but the current crop of online translation options are all insufficient even with the understanding that some elements of language defy translation.

Companies like Gengo are trying to bridge the gap between free online translation options and manually hiring a translator, by offering online language translation conducted by qualified translators around the world. Gengo’s roster of experts comes at a price; it’s difficult to imagine a service like that working on a volunteer level, although of course there are crowdsourcing behemoths like Wikipedia that fuel many to keep believing that the wisdom-of-the-masses model has a chance of succeeding.

In reality, the Internet will likely never be fully translated. The crowdsourced vision from von Ahn is productive not because it’s moving us closer to a reachable goal but because Duolingo is a very good language learning tool and it does help people communicate with others… but the continually growing catalog of content means there’s just no way we could ever get through everything, not in a million years.

The best bet, then, are the algorithms embraced by Google and Microsoft, albeit algorithms monitored and adjusted by people.

You’ll have to leave a comment if you’re reading this translated into a different language. Perhaps 10 years from now you won’t even notice that it’s been translated.

Illustration by Jason Reed