As Moldovan officials sit down to plan out the latest chapter in their country’s 20-year experiment with democracy, they won’t be alone. Starting Oct. 16, they can login to a Web community geared for leaders just like like them.

Called the Leaders Engaged in New Democracies (LEND) Network, it’s an online club for top officials in transitional countries—a place to ask questions and navigate the often treacherous pathway to democracy.

With high-tech donations from big private companies like Google and experts provided by the Club of Madrid, the world’s largest forum of former heads of democratic governments, LEND aims to forge a new frontier in technology and governance. The brainchild of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton herself, the network serves as a Facebook for leaders for governments in emerging democracies, from Libya and Mongolia to Moldova and the Syrian opposition movement.

“There’s a broad body of evidence that provides ironclad proof that technology and social media can bring down bad governments,” said Dr. Tomicah Tillemann, senior advisor to Clinton for civil society and emerging democracies and the State Department’s point man on the project. “What we don’t know is if social media can build up better governments to replace them.”

Tillemann and his cohorts in the Community of Democracies, the non-governmental organization that is overseeing the project, are certainly going to try.

Building a new democracy isn’t exactly easy. You can find more instructional manuals for building a nuclear bomb online than building a new democracy. Leaders are stuck in a dangerously isolating information black hole.

“In new democracies, if you’re a leader thrust into this position, there’s no tech support line you can dial that will give you step-by-step advice,” Tillemann said. “This is really tough stuff and there’s no user manual for a new democracy.”

At it’s simplest the LEND Network is a kind of digital rolodex of democracy experts, organized by expertise. Need to rewrite your constitution following the collapse of an authoritarian government? Head over to the profile page for Pius Langa, the retired South African chief justice. Need to rebuild the national security apparatus? Chat up Emil Constantinescu, the former president of Romania, a country, which Tillemann noted, “had to dismantle a massive state security apparatus after the fall of dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu.” You won’t find that kind of expertise on Twitter.

On a deeper level, the network aims to be a hub of public policy communities—basically old-fashioned Web forums restricted to experts organized around specific topics.

It’s a smart solution for a tricky problem. Transitional governments are truly delicate things: You don’t have to look much farther than Russia to see an ostensible democracy slowly creeping back towards autocratic ways. Myanmar’s democratic reforms in 1962 turned into 60 years of autocratic rule from a military junta. There are success stories, too: South Africa, Chile, and Romania, to name just a few.

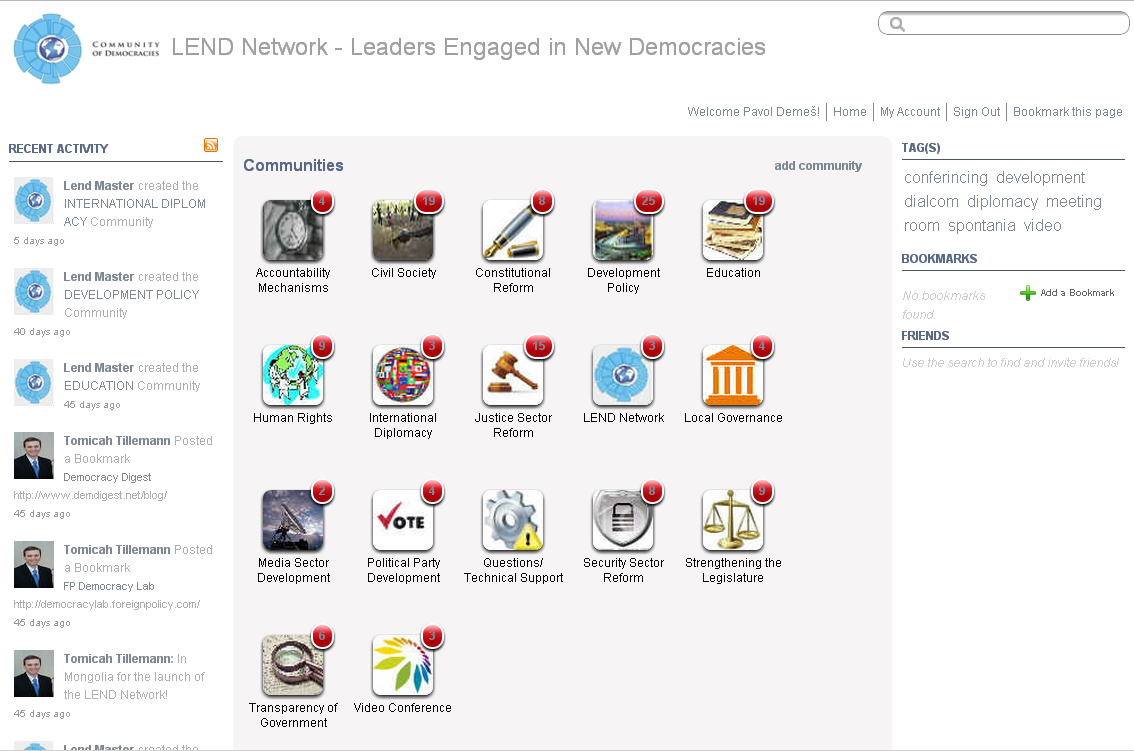

The network is closed off, so you can’t give it a test run (unless you’re a former president), but Tillemann did provide the Daily Dot a screenshot.

It’s not pretty, but you can excuse the creators for skimping on a sexy design and focusing instead on functionality. Reddit took over the world of social news with a bland and bare-bones design; LEND needs only to work for a few hundred leaders worldwide.

It’s worth noting that not everyone agrees with Tillemann’s conclusion that social media played a key role in taking down autocratic governments. The New Yorker’s Malcolm Gladwell famously argued that social networks thrive on so-called “weak ties,”—the type of connection formed among acquaintances rather than family and friends. “The Internet lets us exploit the power of these kinds of distant connections with marvelous efficiency,” Gladwell wrote. “But weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.”

Where revolutions have succeeded, critics argue, it’s less to do with Facebook and Twitter and more to do with meaningful bonds formed among activists suffering from the floundering economies, institutionalized violence, and general repression typical of autocratic regimes. There were certainly revolutions long before hashtags and Facebook likes.

Both sides are somewhat right: Social networks are ultimately just tools for sharing information. Their success depends on a combination of who is using them and how.

In the case of the LEND Network, Tillemann and the State Department aren’t trying to start any revolutions. They’re smartly, if perhaps not purposefully, playing to the strengths of weak ties: Social networks are powerful platforms for information sharing and collaboration. And in those categories, the world leaders are currently stuck somewhere in the digital Mesozoic. LEND may just yank them into the 21st century. What will that mean for the future of democracy?

Tillemann, who boasts a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University and is a former policy advisor to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, admits the LEND Network may have a bumpy road to success, not unlike the startup Web platforms that were its inspiration. In fact, Tillemann made a direct comparison between his role on the project and that of a private sector investor:

“My job is to act like a venture capitalist and find the best ideas we can for supporting democracy and activists around the world, then bring together the right partners, the right people, and the right technology to make these ideas a reality.

“This is uncharted territory and it’s going to be an adventure.”

The program saw a limited test-run in July, at a meeting in Mongolia attended by that country’s president, Secretary Clinton, and Estonia’s foreign minister. It officially launches first in Moldova on Oct. 16, and will expand to Tunisia and other countries over the next year. According to Tillemann, Kyrgyzstan, Burma, Libya, and even the Syrian opposition have expressed interest.

Photo by US Mission Geneva/Flickr