Over the course of his career, Vice journalist Jason Leopold has filed thousands of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, attempting to gain information about the inner workings of the federal government. At a hearing before the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on Tuesday afternoon, Leopold asserted that that process almost never works as it should.

“I have submitted thousands of FOIA requests to dozens of different agencies,” he testified. “In my experience, fewer than 1 percent of my requests have been fulfilled in the time frame required by [law].”

Passed in 1966, the Freedom of Information Act is designed to give American citizens a window into their government’s inner workings. Under the act, people can request government officials make public specific documents produced in the course of their duties. Over the decades, it has become one of the most important tools for reporters and good-government advocates looking to expose not only the bad behavior on the part of government officials, but also to simply understand what’s being done with taxpayer dollars.

If he could get a signed release from the Hezbollah fighters who imprisoned him for six years, the documents would be handed over.

As a cadre of journalists and nonprofit officials working toward government transparency testified on Tuesday, the promise of FOIA to shed light on the inner workings of government is falling far short of its true potential. Panelist after panelist decried interminably long wait times for agencies to turn over requested documents. When those documents were eventually turned over, they were often so heavily redacted to render them complete useless.

The hearing was called largely to look into the issue of growing backlog of unfulfilled FOIA requests. Recent years have seen the number of FOIA requests skyrocket. According to figures from the Department of Justice, between 2012 and 2013, the number of unprocessed FOIA requests increased by 32 percent. Over the next year, the jump was 70 percent.

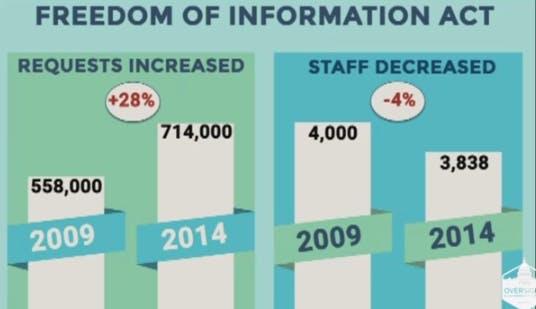

The problem, officials argue, is that the number of FOIA requests is growing rapidly. In 2009, there were 558,000 FOIA requests submitted by members of the public; by 2014, that number had risen to 714,000. At the same time, the resources government agencies have alloced to processing FOIAs has moved in the opposite direction.

“Congress cannot continue to slash agency budgets, starve them or their resources, cut their staffs, and all the while expect them to tackle an increasing number of FOIA requests, which are now at an all-time high,” Rep. Elijah Cummings (D-Md.) said during the hearing.

The inability of government agencies to handle the deluge isn’t universal. A full 92 percent of the backlog comes from just six agencies—the Department of Homeland Security, the State Department, the National Archives and Records Administration, the Department of Justice, the Defense Department, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

As of 2014, Homeland Security alone had more than double the amount of outstanding FOIA requests as the other five agencies on that list combined. A large number of requests made to the notoriously opaque DHS stemmed from undocumented immigrants attempting to get information on their own deportation cases.

Many of those who testified during Tuesday’s hearing argued that the growing imbalance between the demands put on the FOIA system and the resources devoted to it certainly plays a role in the backlog, but the core problem runs far deeper.

“Federal agencies claim they lack funding and staff … but I also see they create much of their own backlog by requiring even the simplest requests to go through the onerous FIOA process when it’s not necessary,” said Sharyl Attkisson, an Emmy award-winning investigative reporter who spent over two decades with CBS News.

“They’re creating their own backlog at their own expense,” she continued. “It used to be that if a government official had a document just sitting on their desk, they’d just give it to you. Now they use FOIA to make you go to the end of a long queue to be answered—thereby creating this backlog themselves, I think intentionally.”

Attkisson recounted how she filed a request for information on the spread of the Enterovirus in the United States last year, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officials told her they were too busy dealing with the Ebola crisis to process her request. Eight months later, Ebola is no longer a threat in the U.S., but the agency has yet to turn over documents.

“The root cause of all of these problems is the lack of an independent, robust organization that monitors and enforces FOIA compliance throughout the federal government.”

The issue for the media is that a piece of information becomes less newsworthy with the passage of time. Most stories have shelf-lives, especially in today’s Internet-enabled, non-stop news cycle. The law dictates FOIA requests are supposed to be processed within 20 days, although government officials are allowed to push that deadline back—and do in most cases. “If I want to file [a story] in less than three years, I don’t file a FOIA,” testified Leah Goodman, a senior staff writer and finance editor at Newsweek.

Delays aren’t the only problem with getting officials to turn over information. The are a number of exemptions to the FOIA law that officials are able to use as methods to avoid disclosure.

Former journalist Terry Anderson recounted a 4-year fight he had with the government in an attempt overcome exemptions used to prevent him from obtaining some very important information. A former U.S. Marine, Anderson worked in Beirut as the chief Middle East correspondent for the Associated Press in the 1980s. In 1985, he was kidnapped by Hezbollah and held in captivity for six years.

After his release, Anderson started writing a book about his experience. A key component of that process was getting information on his captors from intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Anderson testified that the Drug Enforcement Administration told him that it couldn’t turn over information about his kidnapping because doing so would violate the privacy rights of his kidnappers. If he could get a signed release from the Hezbollah fighters who imprisoned him for six years, the documents would be handed over. Needless to say, Anderson didn’t see that as a realistic possibility.

Anderson followed in the footsteps of so many others who have been frustrated by roadblocks put in the way of their FOIA requests: he sued. When a court eventually ordered the DEA to turn over the documents, Anderson was finally able to see the information that was being kept from him—copies of news stories he had written for the AP, publicly available reports that for some reason had been stamped “top secret,” and embarrassing emails from diplomats making derogatory comments about foreign leaders.

“The government spent millions of dollars and 4 years of effort trying to protect secrets,” Anderson said, “not one of which concerned actual security interests of the United States.”

Using the courts to force the government to comply with a FOIA request is an all too common occurrence. David McCraw, assistant general counsel for the New York Times, said the paper filed eight FOIA lawsuits last year alone.

McCraw recounted how, late last year, the Times made a request to the Department of Justice asking how much the agency spent reimbursing the legal bills of FOIA requesters in the Southern District of New York City. The law permits the courts to award attorneys fees in cases where the requester wins. Weeks passed without an adequate response. The Times followed up with the DOJ 10 times before filing a lawsuit. The suit caused the U.S. attorney to get involved, which is what finally prompted the DOJ to turn over the information.

“Much of the delay has little to do with the nature of the requests, but instead results from a culture of unresponsiveness,” said McCraw. “Some agencies are consistently good, but other show little improvement year after year.”

There was a consistent push among Republican members of the Oversight Committee to pin the blame for the federal government’s problems fulfilling FOIA requests specifically on the Obama administration, over and above what existed in previous administrations. Most, but not all, of the journalists on the panel categorically lay blame at the president’s feet for creating a newfound unwillingness among executive branch agencies to provide information.

McCraw reckoned there hadn’t been much of a change since the previous administration. Goodman said the shift happened after 9/11, in the early year of the George W. Bush administration, when a “fear culture” arose among many government officials.

“The difference between this administration and the last administration was that the Obama administration signed an executive order about a new era of openness,” noted Leopold. “With the Bush administration, I knew I wasn’t getting anything.”

It should be noted that both Congress and the White House are exempt from having to comply with FOIA.

Despite pledging early on to be “the most transparent administration in history,” the Obama administration has a difficult history with FOIA. The administration issued a memo calling on agencies to run requests “that may involve documents with White House equities” by administration officials before their release. In 2001, the Department of Homeland Security was embroiled in a scandal where political appointees were accused of altering the document-search results for FOIA requests from media outlets and nonprofit groups viewed as hostile to the administration.

To be fair, Attkisson asserted that she had seen similar memos circulated by both the Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton administrations.

“It used to be that if a government official had a document just sitting on their desk, they’d just give it to you.”

Witness after witness blamed a long-standing culture of secrecy as the core motivation behind agencies not only consistently fighting FOIA requests, but also turning over documents that were heavily, if occasionally comically, redacted. Leopold recalled one instance of receiving a document from the Defense Intelligence Agency—an assessment of the damage to U.S. intelligence efforts caused by the leaks of former NSA contractor Edward Snowden—that was just 150 completely blacked-out pages.

Leopold also told a story about attempting to gain access to the reports created by the Pentagon’s in-house think tank, the Office of Net Assessment, on issues like the future of warfare technology or predictions about the long-term political situation in the Middle East. After pestering the agency repeatedly, he was informed that officials would turn over reports, which aren’t classified, if he promised to never file a FOIA request with them again.

The personal relationships between the people making FOIA requests and the agency officials granting them, often comes into play. Noting the absence of any Washington editors from major newspapers on the panel, Goodman testified that she spoke with a few of them, and they said they stayed away from the hearing due to “concerns about a chilling effect for even speaking out on this [issue].”

The problem, the witnesses argued, is that there are no repercussions for agencies that subvert the intent of the law by ignoring, slow-rolling, or overly redacting documents in FOIA requests. Departments are required to issue annual reports, like this one from the Department of Homeland Security, showing stats on their compliance with FOIA requests, but no one really ever seems to be punished for poor performance.

Combine that lack of enforcement with a culture where a government bureaucrat seems more likely to face admonishment for turning over something he or she shouldn’t have than for not turning over enough, and it creates a set of incentives that reward stonewalling.

There have been legislative efforts to fix the problems with FOIA. Earlier this year, Rep. Cummings joined with Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), who used to chair the committee, to introduce the FOIA Oversight and Implementation Act. The bill would makes changes, like limiting the scope of the type of documents a single exemption can contain and directing the Office of Management and Budget to create a central portal for all FOIA requests. The bill passed unanimously out of committee, but has yet to be scheduled for a vote.

While praising the bill, Nate Jones—the director of FOIA at National Security Archive, an organization that’s filed over 50,000 FOIA requests over the years—insisted that even making those common-sense reforms to the law would fall short unless an enforcement mechanism was also put in place.

“The root cause of all of these problems is the lack of an independent, robust organization that monitors and enforces FOIA compliance throughout the federal government, a FOIA beat cop,” he said. “My fear is that, without robust enforcement … [even a reform] bill won’t fix the root cause of the problem.”

Photo by kev-shine/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)