Remember when Facebook was a social network specifically for college students? This was back in 2005, when iPhones were just a twinkle in Steve Jobs’ eye and Kim Kardashian was just Paris Hilton’s dark-haired accessory. Back then, Facebook was exclusive property of college students who felt free to post insults and bong-rip pics without fear of parental tsk-tsking or future consequences. A time when people actually considered using the poke button, and nobody’s great aunt even knew the site existed. A simpler, arguably sweeter time.

Obviously Facebook grew to be a much larger and more encompassing kind of network, but as it expanded, it left a vacuum for apps that cater to college kids who want a network specifically for their friends. In its place, a variety of mobile apps have gained favor among young people, in particular Snapchat, Twitter, Tinder, Secret, and Whisper. But none of these new apps have the college-only-ness that helped propel Facebook.

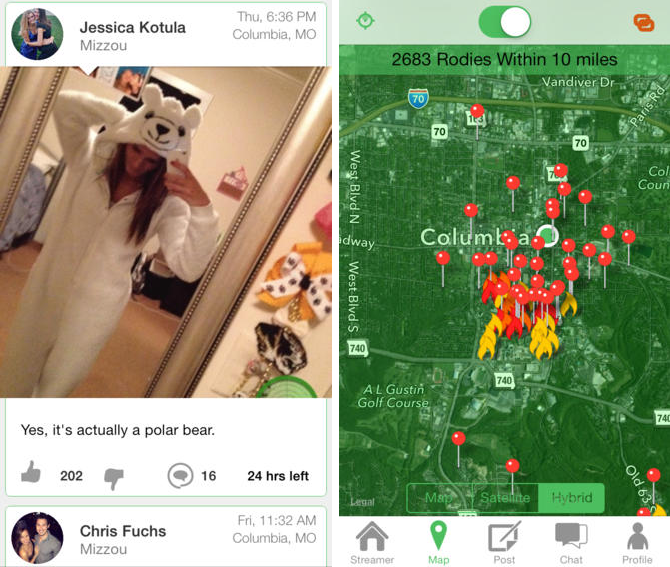

Social media abhors a vacuum, and now an upcoming app wants to fill the void left by the old, college-only Facebook. Erodr is a small app with niche appeal: It’s a mobile-only hybrid of Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, Instagram, and Whisper—and it’s gaining student users at the universities it supports.

Like Instagram and Twitter, Erodr allows people to share photos and text into a feed. Like Snapchat, these posts aren’t around forever—the name comes from the idea that these posts “erode.” They disappear after 24 hours (though, of course, it’s easy to screenshot). Like Whisper, you can post anonymously, which leads to a proliferation of unidentified body parts. When you “like” or “dislike” (yep, there’s a dislike button) something, only the user of the post can see your response. Like Grindr, “Rodies” can bump into each other on the ground in real-time, because there’s a location-sharing feature. Like Facebook in its early years, to access the app, you need a college email address associated with a university it serves.

Of course, just because Erodr is only for college students doesn’t mean it’s the next Facebook. Erodr is growing at a much slower rate than Facebook did when it went from dorm room experiment to young-person obsession in a matter of months. Erodr’s been around a little over a year now, and it’s still a cult hit at a handful of schools, not a spreading phenomenon. The team is small (five people in California) and they were bizarrely hard to get ahold of considering I’m a journalist trying to write a story about their startup; that lack of media savvy suggests they’ll need outside help before taking the app to the next level.

And competition is stiffer now; when Facebook came out, the closest thing to it was MySpace, and it managed to course-correct many of MySpace’s problems in a way that made it enormously attractive to college students. Erodr doesn’t offer something completely new so much as it takes elements from every popular social app and network and mashes them together into a Frankenpastiche of a young person’s app.

Drew Halliday, the app’s young creator, started Erodr while attending the University of Missouri, which is where the app beta tested and where it has the most enthusiastic following. “On several campuses we are getting to about 50 percent of undergrads registered, all by word of mouth. We’ve intentionally kept growth limited to the pilot campuses while we refine our product,” Halliday told the Daily Dot.

Even though the app is only available at a small number of midwestern and southern schools, many of these universities are experiencing remarkably high user engagement. Fans are calling themselves “Rodies” and bars around the college campuses are offering specials for the social app’s users.

Erodr anonymous masked speed dating event at donnas. Free drinks for participants. Specials for everyone else #erodr pic.twitter.com/74OtbJgR1a

— JMU Party Problems (@JMUPartyProbz) November 20, 2013

The whole “Rodie” thing reminds me of the Chive fans—meaning the bro vibes are strong with Erodr. At Indiana’s DePauw University, the app has already been the subject of hand-wringing op-eds in the student newspaper; a student writer worried that it glorifies hard-partying. Then again, Halliday showed me a heartfelt post from a user (with that user’s permission) about how he shared a post about a hospitalized friend and was touched by the support he received via the app.

So while it may get embraced by fratty types, it may be premature to reduce the app to a mere advertisement for debauched Greek life. At the campuses it’s available at, Erodr is growing to be a part of the social fabric in a way that’s strongly reminiscent of Facebook’s early days.

I got a Facebook account in 2005, right before I went to school in a different country where nobody knew me. In the month leading up to moving, I used it extensively to creep on the people in my year. I accepted friend requests from strangers, in the hopes that we’d be friends. When I finally got to school, I ended up befriending people I met in my dorm and didn’t do much to reach out to those Facebook-stranger-friends. But I did end up working on a project with this impossibly pretty girl I met because she liked how I quoted Dr. Evil in my profile (at this point, people actually read Facebook profiles, and yeah, admitting to liking Austin Powers helped me MAKE a friend, which defies logic). Nowadays, you can’t browse through your entire campus network, and etiquette surrounding Facebook is more ingrained, so the kind of stranger-friending that happened in the early days is definitely not encouraged. This is where Halliday wants Erodr to come in; the app is meant to encourage real-life interactions and friendships just as Facebook once spurred spontaneous IRL moments across college campuses.

And it already is. “Many of my friends I have now, I have met through the app,” Mizzou student Kirsten Yocks told the Daily Dot. Yocks especially likes the option for anonymity, which she sees as a tool to help students post content they’d otherwise feel too vulnerable to share. “The anonymous feature offered a lot of funny and touching posts that some people would have otherwise been unwilling to write [publicly],” she said.

The anonymity feature was recently turned off while the app was being updated, but lucky for Yocks and other students, it’s back. This is what’s likely to spark the most concern from parents and school administrators, since anonymity can give bullies protection, and on Erodr, some students use the anonymity feature to post cleavage shots and rude comments. But, of course, the opportunity for telling secrets is what draws other students to the app, and may help it compete with apps like Whisper and Secret, which also allow anonymous confessions and cater to a young crowd.

And anyway, many students choose to post under their names, and the fact that it’s only available for college students makes people feel like they’re interacting with a digital co-hort, not an online stranger.

Well, just saw on erodr that some kid needed a ride home, so I went to Walmart picked him up and gave him a ride home. I’m way too trusting.

— Emiline Donald (@emdon3000) March 14, 2014

Since I’m no longer a college student, I couldn’t download Erodr. In fact, the only way I found out about it was through my 19-year-old brother, who attends Mizzou. Halliday did not let me demo it and seemed chagrined when I told him I had peeked at my brother’s feed; he emphasizes the exclusivity element because he wants college students to view it as a more private space than apps like Facebook, and even though Erodr shares some similarities with the social network, Halliday is quick to point out differences.

“Erodr has a very different privacy model than Facebook,” he said. “We don’t retain posted content on our servers beyond expiration.” And there’s no profile-browsing happening on Erodr. “Facebook users could look through the profiles of other students on Facebook, while on Erodr users are invisible until and unless they post to the public feed, or ‘like’ or comment on another person’s public post to reveal themselves to that person,” Halliday explained.

Erodr is gated. Users do have ways to cross-post their Erodr activity; they can embed their posts on Twitter, for example, but you have to have an up-to-date college email to gain access. For now, it’s an app that limits its audience on purpose, an app that wants to stay niche. Halliday’s goal is to get Erodr on every college campus, but he has no plans to expand the app to an off-campus crowd.

Will Erodr rise to the kind of must-use status Facebook did for the undergraduates of the next decade? It has all the right ingredients, but that doesn’t mean it will alchemize into the next Snapchat or Whisper, especially since Halliday and his team are relying mostly on word of mouth right now to spread to new campuses. And if it does spread, they will have to hire experts to make sure the privacy protections they pride themselves on stay secure.

But whether its popularity fizzles out or not, the embrace of Erodr by student bodies like Mizzou and DePauw shows that there is a market for this kind of app—and that there’s still an app for this kind of market.

Photo via Erodr