In the desert, you know when an invasion is coming. Across the horizon, you can see it from miles away. So naturally, Burning Man, the weeklong festival held in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert every summer, has seen its high-tech future coming—even if it’s not sure what to make of it.

While big art installations have always been a part of Burning Man, technology is increasingly becoming the basis for the large-scale creative works concocted at the festival—to say nothing of the Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, selfie sticks, GoPros, and apps that have slowly transformed the festival.

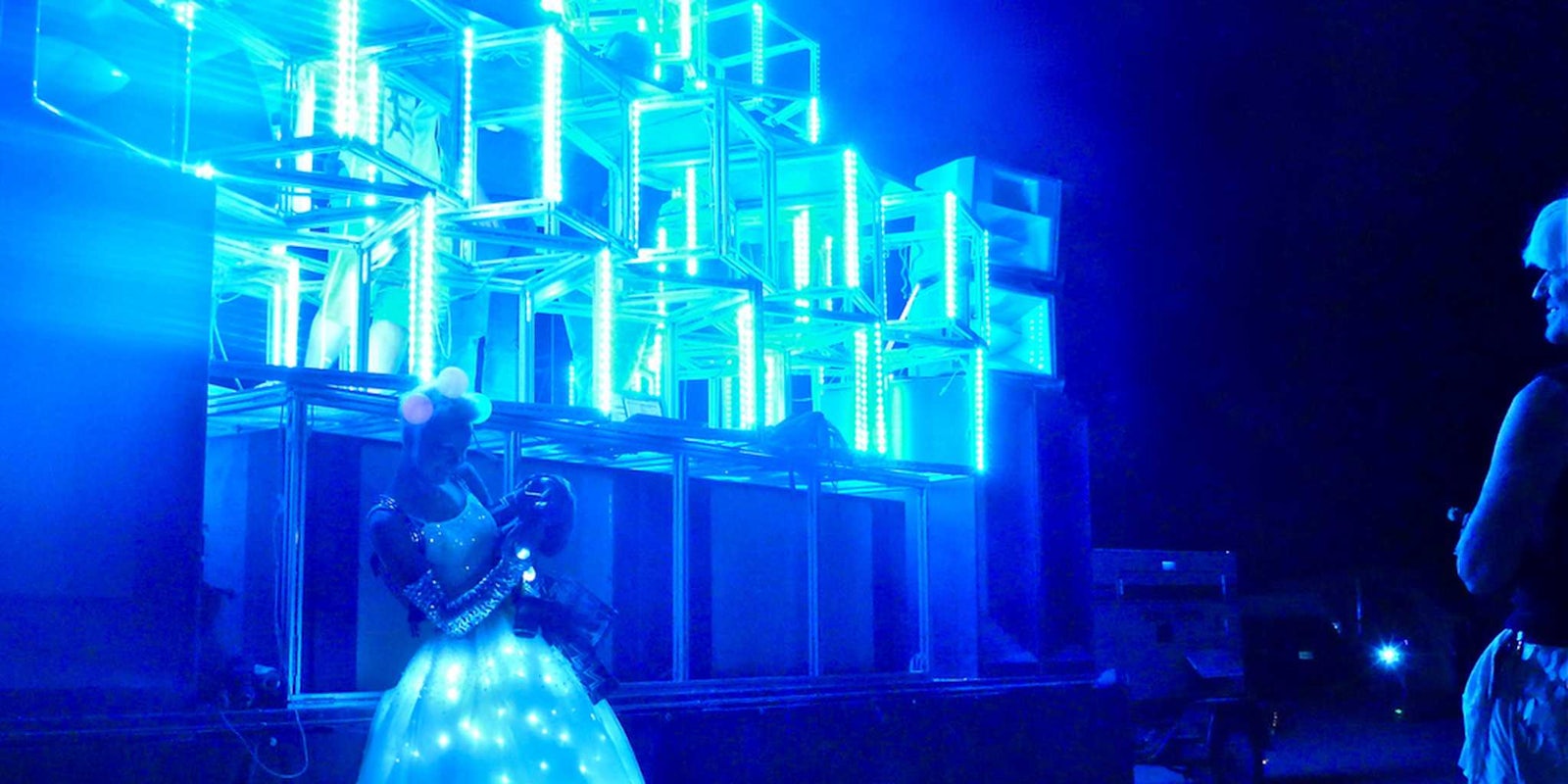

Take, for example, lumenEssence, a sculpture made up of 33 interactive and dynamic towers surrounding a central viewing platform that serves as a housing area of festival-goers. Each tower is 30-feet tall and illuminated by LED lights.

“I’m a software developer, but I was a mechanical engineer by training,” says Mauricio Bustos, the creator of lumenEssence, via Skype after a long day of setting up the structure, his Internet connection iffy but relatively stable. “I’ve been at Burning Man since ‘97, and doing bigger and bigger projects. The group I hooked onto a few year ago, we kind of exploded in the largeness of the projects and we wanted to pursue.”

Bustos says that most of the team behind lumenEssence are friends and fellow parents from his kids’ school. The installation is actually recycled from last year’s creation, Seagrass. Seagrass used LEDs and capacitive touchscreens to create interaction between people and the design. Colors would emanate from a tap to the screen. Now, lumenEssence has updated that idea: Attendants can take an elevator up the structure, where there are capacitive metal touch devices. Those connect to the LEDs and change their lighting patterns.

LumenEssence being assembled at Burning Man.

Photo via Facebook

“You can have a playfulness with the sculpture itself,” Bustos says. And if no one is playing with it, “the lights are networked together through radios so they create their own patterns and displays that you can see from a couple of miles away.”

Mads Christensen, the creator of communication experiment Ripple, says he was spurred to go high tech with his installation back in 2005, when he saw LED sculptures showing up.

“I realized how much LED technology had evolved since I studied electrical engineering back in the 90s,” he says. “That really inspired me to start creating light sculptures using LEDs and custom software.”

For Ripple, Christensen also took cues from nature.

“I was inspired by the way ants communicate using touch to relay messages to each other about where to go find water, food, etc. This communication happens without a central master or dispatcher and it fascinated me how these seemingly simple insects are able to communicate such advanced information to each other.”

Ripple essentially allows participants to do the same thing; the individual nodes can connect with their immediate neighbors, and they use infrared light to receive and send messages. The resulting light sequences are created by the nodes working together. Thanks to a Burning Man art grant, Christensen was able to add photovoltaic cells and rechargeable batteries to Ripple as well, so it can stay powered for a full week.

“I am curious to see how people will react to Ripple at Burning Man,” Christensen says. “I feel the open desert setting is ideal, because it allows the installation to be viewed from all sides. Viewers will be able to interact with the installation by walking between the nodes, thereby blocking the infrared signals, blocking or distorting the communication between the nodes, which in turn will alter how the light sequences are generated.”

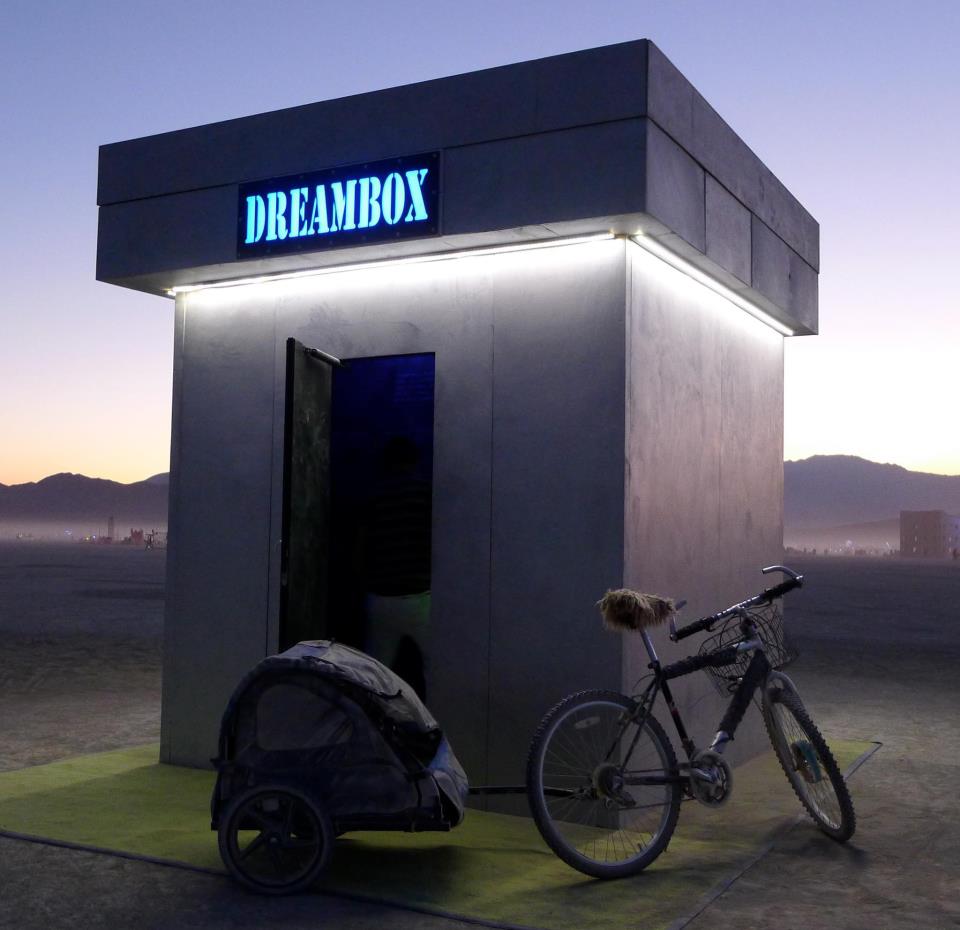

DreamBox 3.0 is arguably the Burning Man installation with the most significant Internet presence. (This is its third appearance at Burning Man, hence the “3.0”.) Physically, DreamBox is a 10-foot cube with a waiting room and a recording booth. Participants enter, then—after using a touchscreen device to type out their names and email addresses, and agree to standard legals terms—look into the HD camera and describe their dreams for 30 seconds.

The project pairs with Dreamus, a Web community where people can describe their dreams or donate to making others’ dreams come true. “Dreams are more likely to come true if you share them with others, online,” says creator Teddy Saunders, a filmmaker and photographer who also runs his own production company. “I think we’re [DreamBox] one of the first art installations that gave birth to an online Web platform that reaches beyond the borders of the playa and connects Burning Man participants to the outside world in a timeless way that lasts after Burning Man.”

Photo via Facebook

Unfortunately, Saunders has found himself and DreamBox in Burning Man’s technological gray zone.

“Our plan with DreamBox 3.0 was to put a satellite on the DreamBox so that people could immediately share dreams,” Saunders recalls. “However, at the last minute Burning Man’s media department put the brakes on us after their art department already gave us full support as an honorarium project. It’s pretty embarrassing actually. We’re saddened that they are hesitant to allow their participants to share such beautiful intentions.”

Saunders also says there are 12 short films he created about the Dreambox project that the media team won’t allow him to release because Dreamus features a donations option—and that this is an act of “commodifying” the festival.

While Saunders’ personal situation is harmless, you can’t help but sympathize with the caution of Burning Man organizers. You need look no further than the celebrity swag bags of Coachella or the tweet-controlled Doritos machine at SXSW to understand the impact that money can have on a festival.

“I hope to be able to figure out a solution with them so that everyone can benefit,” Saunders says. “But it’s definitely an interesting new topic of conversation considering all of Silicon Valley moguls are now spending thousands to stay at Burning Man hotels. I hear they are even doing Burning Man Google Maps Street Views this year.”

He makes a valid point: There is some picking-and-choosing going on, which Burning Man readily acknowledges. In a page dedicated to addressing rumors and myths about the event on its site, the statement “Burning Man is propagated on the Internet” is discussed. In short, it sounds like Burning Man feels like most of us do about the Internet: It’s how and where we do and talk about things now, so of course it’s going to be utilized

“[Burning Man’s] method of propagation has been person-to-person, and in recent years, this communication has principally occurred on the Internet. Many groups distributed over a large geographic area now meet in real time and real space—precipitated into social contact by Burning Man and the communication tools provided by modern computer technology.”

Despite this common-sense attitude, it’s clear that Burning Man is stuck in an uncomfortable spot between promoting new creative feats and honoring its roots by encouraging festival-goers to embrace “immediacy.” In a recent blog post on its site, there’s an even deeper dive on how technology changes the environment.

“The tech culture of Silicon Valley is the embodiment of ‘can’ equals ‘ought’– if we can do something, we ought to. All advances in technology are seen as good advances, and no use of technology is considered out of bounds. Does that strike you as a sweeping statement? It shouldn’t: Facebook and OKCupid have both been caught running social experiments on their users without their permission, Google never asked permission to take street photographs and happily collected Wi-Fi data as it went. They’re all spying on us.”

The same post also acknowledges that “an event in the desert founded on radical self-reliance can’t be anti-technology.” Another blog entry introduces iBurn, the Burning Man festival app.

While Burning Man appears caught in a contradiction, it’s one that’s emblematic of a larger societal concern: We’re all confused about the best ways to use technology without letting it consume us, and if anything, there is some astounding beauty being created at Burning Man. There’s a reason this high-tech experimentation has found a home at the festival.

“The thing for me is that I was trained in engineering so it’s an opportunity to express artistic ideas and visions in what I know how to do,” Bustos says. “And what’s amazing is that people are so receptive to that. People here are very interested in the merging of technology and art.

“The canvas is here so receptive to that, too. The scale is huge; you can really do things you can’t do anywhere else.”

Put a massive group of creative, free-thinkers in the desert, naturally incredible things will happen. It just so happens that a lot of it is connected to the Interent or comes with LED lights.

“Art at Burning Man is commonly very experimental, interactive, and tries to incorporate new technology in its early stages,” echoes Christensen. “It’s a great place to experiment with new ways of expression because the audience is very receptive to nontraditional ideas

And Burning Man isn’t just tolerating these high-tech projects, it’s funding them—all of the projects mentioned here were supported by the festival.

Erick Dunn’s BioTronEsis was among those to receive funding from Burning Man. BioTronEsis is a fiberglass hard shell populated by lit figures. The Burning Man site describes it as a “large translucent cocoon inhabited by a superorganism of hyperexotic alien light creatures. These beings have been programmed to induce meditative brainwave frequencies in humans so as to gently calm you and leave you feeling Ahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh.”

While Dunn and his crew work on setting up the piece, his wife Claudia told me that the installation is an entertainment piece, one that relies on technology to entrance its audience. Using beaglebones (tiny, Linux-based computers), they can control the light and sound animations.

Photo via Facebook

It’s hard to imagine how Burning Man could exist without the Internet now. It’s what helps keep the community together, how I communicated with all of these artists, and where I found out about the individual projects, some of which used sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo for funding.

Technology isn’t going to “ruin” Burning Man, though the concern is valid. At least for the time being, there’s so much else to the festival than LEDs and apps.

“The littlest things you run into here are so amazing and fun, and it’s that balance that makes Burning Man so pleasurable,” Bustos says. “You can see the giant, over-the-top, amazing, high-tech projects, but then you also run into the little things that are the size of your bicycle, that are so beautiful and inspiring too.”

Photo via jurvetson/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)