By DJ PANGBUM

What do Afghanistan and Bolivia have in common? Current geological estimates indicate that the two countries contain the most abundant lithium deposits on the planet. With booming demand, lithium’s geopolitical importance is growing, and it doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to think that both Afghanistan and Bolivia’s reserves are going to be targeted for exploitation. But, what if there was another way? Enter 3-D-printed lithium-ion batteries.

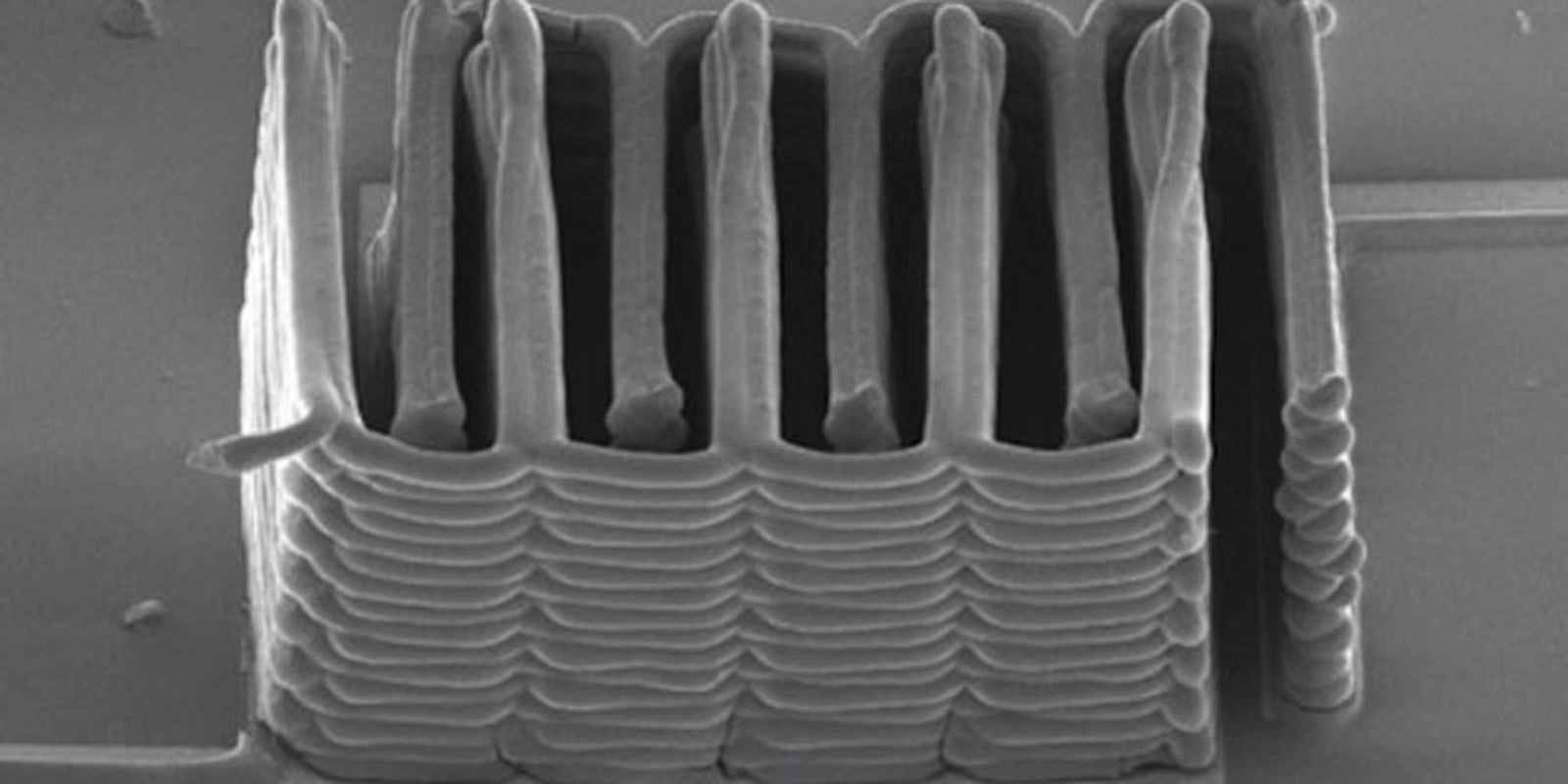

A team of researchers from Harvard University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign recently printed lithium-ion microbatteries the size of a grain of sand. Less than the width of a single human hair, these microbatteries are printed as interlaced stacks of incredibly small electrodes.

“Not only did we demonstrate for the first time that we can 3-D-print a battery; we demonstrated it in the most rigorous way,” said Jennifer A. Lewis, senior author of the study, and Hansjörg Wyss professor of biologically inspired engineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). Lewis’s former faculty position at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign led to the scientific collaboration between the two schools’ researchers. The study’s co-author, Shen Dillon, is an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The group’s study was published online in Advanced Materials journal.

“The electrochemical performance is comparable to commercial batteries in terms of charge and discharge rate, cycle life and energy densities. We’re just able to achieve this on a much smaller scale,” Dillon said.

The demand for lithium-ion batteries, now powering everything from cars to smartphones, is creating a wildly-expanding market. For transportation alone, lithium ion batteries “will grow over 700%, from $2.0 billion annually in 2011 to greater than $14.6 billion by 2017,” according to a Global Information, Inc. report.

Before this 3-D-printed microbattery research took root, device manufacturers had to use other materials to build electrodes. This resulted in poor battery power and life. Lewis’s team uses 3-D-printers to build electrodes out of precisely-constructed layers of ink. According to a Harvard press release, the ink had to fulfill two tasks: exit out of fine nozzles, and then immediately harden into final form. They also had to operate as “electrochemically active materials to create working anodes and cathodes, and they had to harden into layers that are as narrow as those produced by thin-film manufacturing methods.”

Read the full story on Motherboard.