By JAMES ATTLEE

By JAMES ATTLEE

James Attlee, author of Isolarian and Nocturne: A Journey in Search of Moonlight (available in paperback November 15 by University of Chicago Press).

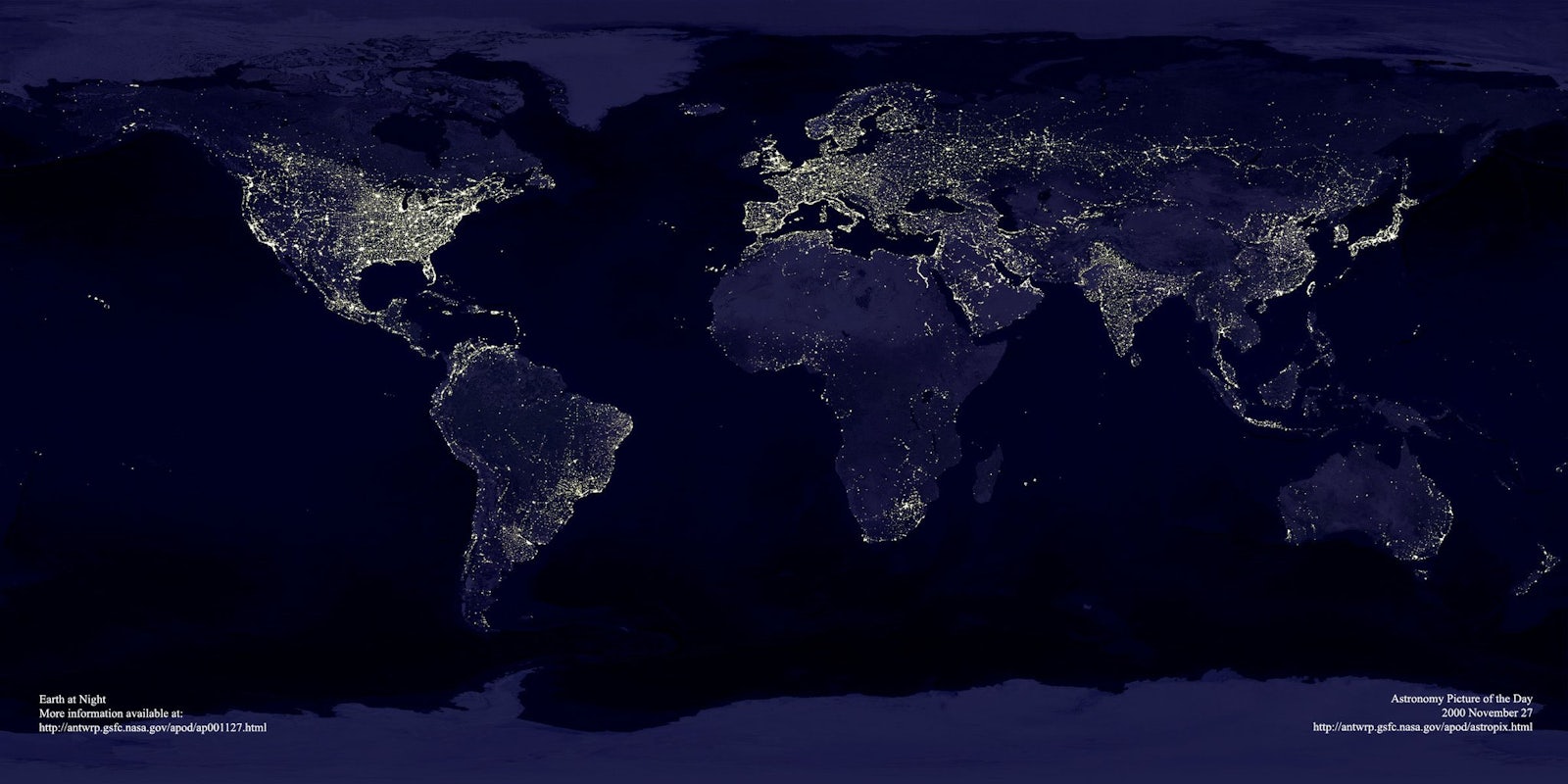

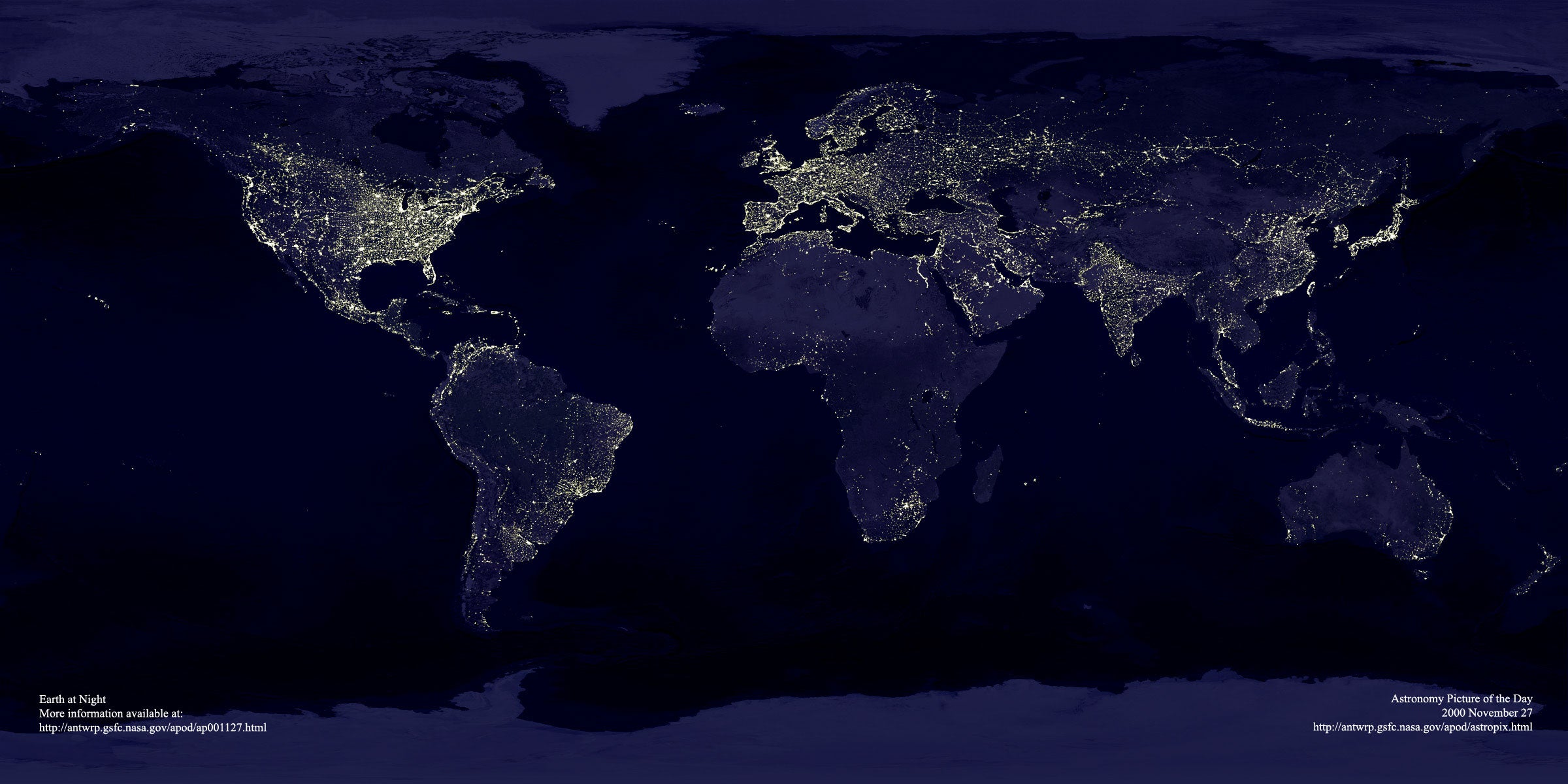

I was lying on my back in a dentist’s chair looking up at the ceiling when it struck me. The dentist had taped a poster there to distract his patients from their woes, a photograph of the earth from space, taken at night.

What I noticed was the simple fact that much of the northern hemisphere is now lit up 24 hours a day. North America, Europe and Japan in particular are glowing around the clock, shot through with rivers of molten gold. Those of us who live in the city no longer experience the night as our great-grandparents would have known it. After countless millennia during which all living things, including human beings, have evolved in response to the rising and setting of the sun, darkness has vanished, like a puddle on the sidewalk at noon.

At the same time we have lost touch with the cycles of the moon, that other great regulator of life governing the tides and providing a clock for human fertility. When was the last time you went for a walk in the moonlight, undiluted by artificial illumination, in the altered world it reveals? Such experiences, long the inspiration of artists and poets in cultures around the world, were commonplace until the rollout of public lighting began barely a century ago.

In the last ten years, the night has retreated even further. Now it’s no longer just a question of streetlights. Even when we draw the shades and lock ourselves into our homes after sunset, we bring light with us. We are constantly gazing at screens, fiddling with our smartphones, checking on status updates, emails and tweets, all the while bathing our faces in technology’s sepulchral glow. While the progress of the evening into night used to bring a gradual withdrawal from the world, a laying down of our daytime roles and a retreat into a private space, the Internet now means we can stay “in touch” at any hour.

What is the last thing you look at each night before you sleep? Your loved one’s face, or the miniature universe contained in your phone? Do you wake to its call in the morning and check your emails before you rise? My day often starts that way. Connection with everybody and everything is the grail of our age, yet its flipside is that it becomes harder and harder to disconnect. (Even as I sit here writing these words I feel the familiar tug, urging me to check my messages. For the moment, at least, I resist.)

What is the last thing you look at each night before you sleep? Your loved one’s face, or the miniature universe contained in your phone? Do you wake to its call in the morning and check your emails before you rise? My day often starts that way. Connection with everybody and everything is the grail of our age, yet its flipside is that it becomes harder and harder to disconnect. (Even as I sit here writing these words I feel the familiar tug, urging me to check my messages. For the moment, at least, I resist.)

And so what? If the night has essentially disappeared, what does it matter? Surely we wouldn’t want to go back to times before electricity liberated us from ending the day when darkness fell. Or depend for communication on a street corner telephone, like drug dealers in an episode of The Wire responding to a pager message—of course not. But there is a loss, this is certain.

***

We tend to forget that we too are animals who have evolved on this planet over countless thousands of years; we are programmed to respond to the rising and setting of the sun and to the cycles of the moon. We cannot expect to dispense with something so fundamental to our makeup and feel no effect.

The impact of artificial lighting on other living beings is clear. Among countless examples, migrating birds are disorientated and crash into brightly lit buildings; insects that navigate by the moon lose their way; deer deprived of night vision by glaring lights are hit by cars; songbirds sing all night, becoming fatigued and weakened. Humans are not immune.

Scientific research indicates that melatonin, the hormone that induces sleep, is produced during hours of darkness and tails off with the dawn. Light intruding into bedrooms fools the body that dawn has broken, inhibiting production of the hormone and therefore reducing our ability to sleep. More worryingly, some recent research appears to have found higher rates of breast cancer among women working the night shift. This has led certain scientists to postulate a link between the low levels of melatonin resulting from long exposure to artificial light and increased risk of cancer.

So my dentist’s chair revelation lead me eventually on a figurative and literal journey. I decided to write a travel book about rediscovering the night. The real night, that is—the one with darkness and stars and moonlight, not the one spent in brightly lit bars or huddled over the screen of a laptop.

***

The first thing I did was to note in my diary for the coming year the dates when the moon would be full. I resolved that these times would find me somewhere outside, walking in its light. This simple procedure, aligning myself with a much slower cycle than a constantly renewing Twitter feed, say, or the inbox of my email account, felt profound; a slowing down, a reconnection with a much older rhythm which existed long before humans first appeared on the planet.

Moonlit nights I would abandon the city to walk in the hills, learning to trust the ability of my eyes to navigate my way in low lighting and reacquaint myself with a night sky not stained orange by streetlights. During the day I researched the art and poetry down the ages that has celebrated the alternate world revealed by moonlight. Gradually my quest led me to take longer journeys: to Japan, where each fall they still celebrate the autumn full moon in the festival of Tsukimi; and to the Arizona desert south of Tucson, where a group of eccentric enthusiasts have built a 90 foot high array of parabolic mirrors they call the Interstellar Light Collector, with which they beam concentrated moonlight onto people seeking relief from a variety of diseases.

Moonlit nights I would abandon the city to walk in the hills, learning to trust the ability of my eyes to navigate my way in low lighting and reacquaint myself with a night sky not stained orange by streetlights. During the day I researched the art and poetry down the ages that has celebrated the alternate world revealed by moonlight. Gradually my quest led me to take longer journeys: to Japan, where each fall they still celebrate the autumn full moon in the festival of Tsukimi; and to the Arizona desert south of Tucson, where a group of eccentric enthusiasts have built a 90 foot high array of parabolic mirrors they call the Interstellar Light Collector, with which they beam concentrated moonlight onto people seeking relief from a variety of diseases.

I came to value my often solitary nocturnal expeditions, disconnected from the brightly lit, online universe as true physical spaces in which to think. As David Crawford, the founder of the International Dark-Sky Association has said, increasing numbers of us spend most of our time ‘in a box, looking at a box’; at an office desk looking at a computer or in our homes looking at a TV.

Perhaps, if you want to think outside the box, you have to get outside the box. However much we love the Internet and all it offers, if we want to add anything of value to its content, occasionally we might do well to step out of the glow of our screens and rediscover the night.

Photograph by Albert Masias, NASA