In Western media, Africa is too often represented as a violent, destitute hellhole in desperate need of Irish rock stars, American film actresses, and Norwegian NGOs just to remain upright.

But the continent is undergoing a renaissance. It’s programming software, making movies, designing clothing, and creating music that is equal to that produced anywhere in the world and frequently exceeds it in quality and creativity.

What South African musician Spoek Mathambo calls “the apartheid afterparty” is not restricted to that country. The sensibility has percolated through the whole continent, so it’s hardly surprising that African artists are creating even their own superheroes.

If you’re an American comic book fan of a certain age, you’re probably familiar with Black Panther, AKA T’Challa, the king of the fictional Wakanda. The Black Panther comics were created by the Marvel team of Jack Kirby and Stan Lee. In other words, they’re about as African as The Lion King.

If you’re a black South African comic book fan of a certain age, you might remember Mighty Man, a high-bounding Luke Cage analogue, according to Nick Wood on his South African Comic Books blog. In his 1970’s heyday, Mighty Man protected black areas against gangsters and dope dealers, but left the political structure untouched.

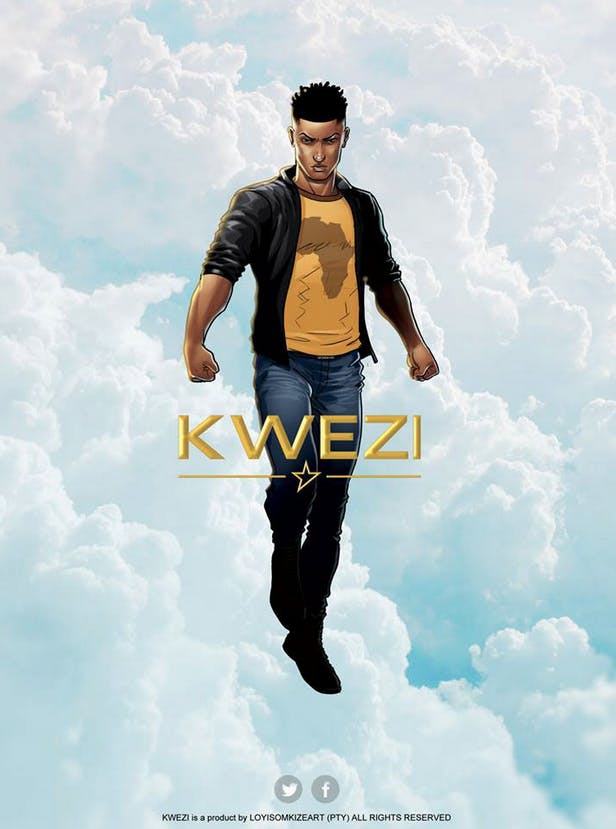

Now, instead of a “local color” superhero like Black Panther (love him though some of us do), or a limited pulp hero like Mighty Man, Africa has Kwezi (which you can read online) and The Pack (available on iBooks and Amazon). Both are attracting attention far outside of Africa.

Kwezi is written and illustrated by South African artist Loyiso Mkize. As quoted in Afropunk, Mkize describes Kwezi as “a young man (who) starts off as an arrogant, opinionated anti-hero who discovers and appreciates his superpowers … the cultural aspect brings him back to his roots.”

Speaking to South Africa’s Design Indaba magazine, Mkize said, “We have never had a superhero that looks like us and speaks like us and shares the same experiences and environment as us. Comic books in South Africa are still at crawling stage. The market hasn’t been tapped into and activated. As someone who is passionate about comics and the power of comics, I see it as a challenge to overcome.”

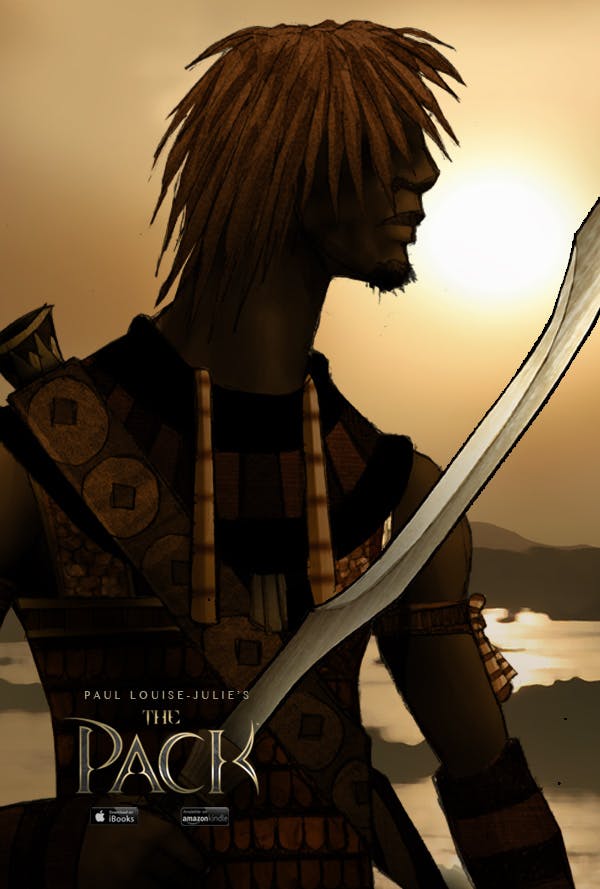

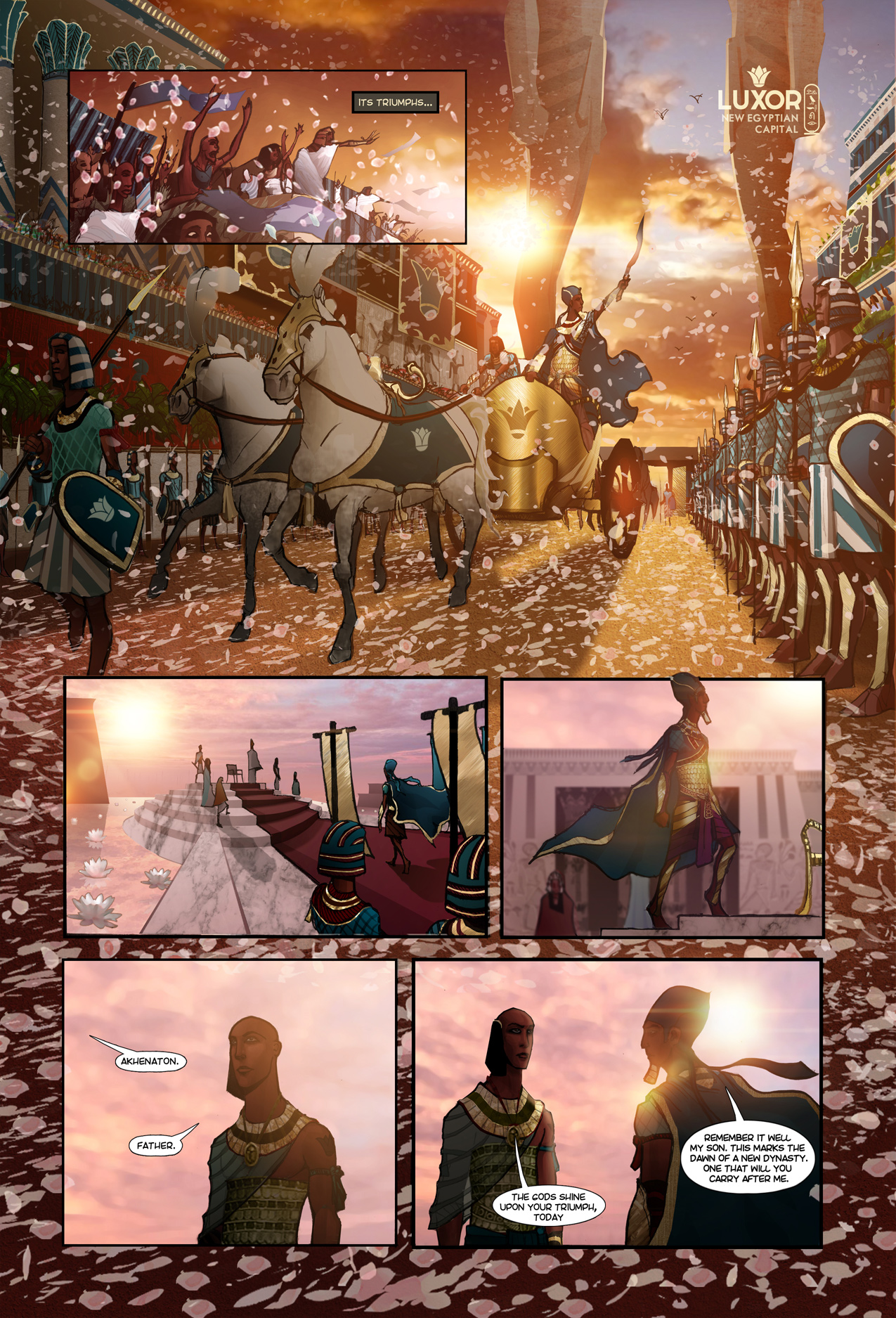

The Pack, an adventure about of a group of Egyptian werewolves, is written and illustrated by Paul Louise-Julie, an American-born and well-traveled artist of French-Caribbean heritage. In an essay he wrote for Bleeding Cool, Louise-Julie said that as a black man he found the Western mythology of comics and his inability to connect with the white heroes deeply unsatisfying.

Then, while visiting West Africa, a Wolof man introduced Louise-Julie an oral historian. They spent hours absorbed the mythology of an epic story-telling session that reviewed the region’s expansive history. Inspired, Louise-Julie embarked on a years-long research project that led him to design more than 30 civilizations to populate his title. He used J.R.R. Tolkien’s work as a template on how to adapt the mythology to make something brand new and ancient at the same time.

“I thought: If I ever want to see more originally Black fantasy completely unrelated to racism or social commentary, I had to go to the roots,” he wrote.

Louise-Julie recently discussed The Pack and the growing interest in African comics in a conversation with the Daily Dot.

Is there a trend of African comic books or am I projecting?

I don’t think you’re projecting. I think that the growing audience for the fantasy genre is sparking more black creators to return to their roots. So yes, I wouldn’t particularly call it a trend so much as a newly booming industry.

Would you call your book a “superhero” book—why or why not?

No, it isn’t a superhero book. Not that there’s anything wrong with them. It’s actually adventure fantasy. Sure there’s an antagonist, but it’s part of a more complex plot. The Pack are werewolves and this story is about them coming to terms with that in the midst of the turbulent fantasy world. In a sense, their supernatural abilities become a backdrop to a more personal narrative.

Do you have readers in Africa?

I honestly don’t know, but I really hope so. The goal of The Pack is to create a newly inspired African mythology that isn’t locked to one particular group, but rather draws from the collective inspiration of Africa’s myriad of cultures so the entire African diaspora can relate.

Are there other artists in the African diaspora with whom you identify? What about within the continent?

Funny thing with that is there are only three artists within the diaspora I can relate with, but they’re all musicians. They are Tiken Jah Fakoly, Toumani Diabeté, and Salif Keita. These men are giants to me as they’ve brought the cultural wealth of their medieval ancestors into the 21st century. It’s extraordinary.

Does self-publishing allow you the extraordinary lengths you go to to create this book? In other words, would a publishing company contract mean you would have to hurry up your work?

Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that it does allow me full control and no bureaucracy in the way of what I want to do—be it production or artistic direction. And no, because I already have to hurry my work as a self-publisher. Most people don’t realize that for a 34-page comic with as much detail as The Pack, companies like Marvel or DC would have a team of seven to 13 people to complete it in a month. I’m one guy doing everything (design, pencils, script, inking, coloring, formatting, publication, marketing, graphic design, etc). But I honestly do enjoy self-publishing, it’s the best setup for me.

There are some elements both Kwezi and The Pack share, aside from being focused on African characters.

There’s a Congolese proverb, “a single bracelet does not jingle.” Like the characters of The Pack, Kwezi does not operate in a vacuum. He works with friends: Mohau, Azania, and Khoi. Another thing that both books share is fantastic art. Realistic but stylish, evocative but gestural, firmly within the realm of comic book art and yet new. Finally, both Mkize and Louise-Julie make these books outside the restrictions (and support) of a publishing company.

One of the drawbacks for creators of African comic books is the African publishing world.

In an interview with the Mail & Guardian, South African illustrator Moray Rhoda summed up the problem in his country, one of the most technically advanced and wealthiest in Africa.

“You’ll find people doing incredible international-level work and then being published (abroad) because none of these local guys has the foresight to support them,” he said. “They won’t trust the vision of somebody who’s the comic book equivalent of internationally respected film and advertising director Neill Blomkamp. They won’t put money behind someone even if he knows what he’s doing.”

That may be where the Internet comes in. If Mkize and Louise-Julie find success distributing their comics online, it may pave the way for other African artists. And if that happens, the publishers will no doubt suddenly realize that they should have supported those artists all along.

Illustration by Paul Louise-Julie