The jailhouse guards promised Le’Char Toki something special for her wedding day. She hadn’t shared a room with the groom—Hau, the father of her 2-year-old son—in the eight months since he’d been incarcerated in the Solano County Claybank Detention Facility in Fairfield, California. And for all five minutes of the ceremony on that late June afternoon in 2015, the guards of the medium security jail let them hold hands. They hauled Hau away as soon as the “I do”s were said, leaving Toki longing for something more.

“I was thinking we might actually get some time together, then they took me off to this little room with a video monitor and told me, ‘Here’s your special visit,’ Toki, 28, says. She wasn’t impressed. “He has moles on his face. The picture is so bad I can’t even see them. I can’t even tell if he’s breaking out.”

Like an increasing number of people with family behind bars, Toki’s ability to have in-person visits with her husband has been replaced with a profitable and controversial system of digital conferencing called “video visitation.” Though a handful of tech firms have made prison communications a billion-dollar industry, the systems can be buggy, prohibitively expensive for the families who rely on them, and, counterintuitively, may even decrease inmate’s contact with the outside world. They can also cut jail costs and, depending on the provider agreements, be a financial boon to the facilities that trade real-life contact for the lens of a webcam.

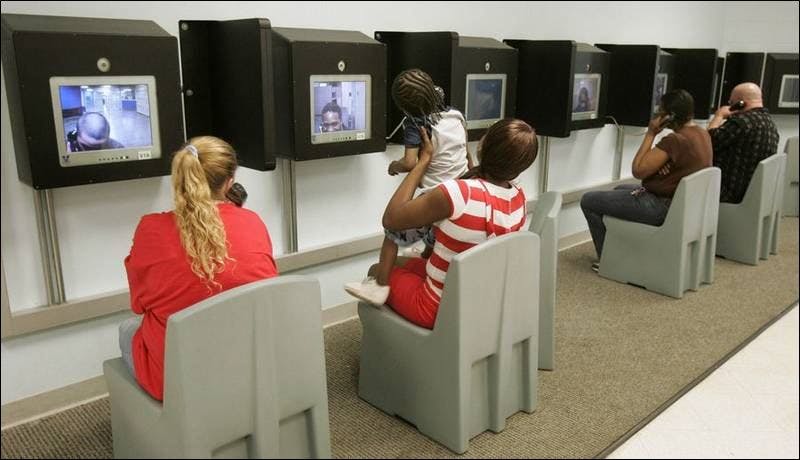

“You go into this little cubicle that’s barely bigger than a bathroom stall,” recalls Toki, describing the experience that served as her sole form of contact with Hau for a little more than a year. “You’re in there and there are four monitors. Two in back of you, and two monitors in front. So it’s like you’re back to back with someone, and they have their visit with whoever, and you get yours. There’s this big pay phone-looking thing next to the screen for you to talk.

“The thing I hate is that you can’t make eye contact. You look into the camera so it looks like you’re looking at them, but if you do that you can’t look at the screen you see them on. If I look at the screen to see him, I can’t look into the camera.”

At least 500 facilities across 43 states have adopted video visitation similar to Claybank’s system, in many cases providing the service at the exclusion of in-person visits. At almost all of the jails that employ the system, video visitation is free on site at the facility, but for those unable to make the trek, livestreaming from home is available for up to $1.50 per minute, according to Prison Policy Initiative data. That’s roughly $1.40 higher than the average price for a local phone call in the United States. The industry is dominated by three major prison communications firms, all of whom employ similar contracts: Telmate, Securus Technologies, and Global Tel Link. As of press time, none of these firms have responded to interview requests. Toki says her service provider was iWebVisit, a smaller firm based in Nevada, which also failed to respond to requests for comment.

On the Securus website, the company invites correctional officers to dream of a world free from the emotional and financial burden of overseeing face-to-face contact (emphasis original):

Imagine no longer having to move inmates, service long lines of visitors, and manually manage visitation schedules. What types of efficiencies could be gained by eliminating these burdensome tasks? Could you increase focus on the safety and security of inmates, your officers, and the public that you serve? With Securus Video Visitation, all of these things are possible.

The problem, according to David Fathi, director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project, is that these firms often “make a condition of their services that video visitation become the only form of visiting available.”

“Adding video visitation as an optional supplement would be fine. Making it the only option available to people and charging for it is not fine,” Fathi says. “That stinks to high heaven. That’s not about security—that’s about maximizing your profit.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ictEY26Tw8M

With an estimated 2.4 million Americans behind bars, inmate communications has long been an attractive market. Video conferencing is merely the latest tech advance in a decades-old business model. Securus has been in business since 1986, for example, and while it rigs webcams today, the tech giant and firms like it made their first and biggest profits providing privatized phone services with rates for local calls billed as high as $14 a minute. The fees were so outrageous that, in October 2015, the FCC capped the rate of prison phone calls at 11 cents a minute for local and long-distance calls, and 14 to 22 cents per minute in local jails, depending on their size. That cap has since been put on hold by the U.S Court of Appeals, pending the outcome of a lawsuit over the cap by GTL and Securus.

There’s enough wealth to go around. As a benefit of signing exclusivity deals with any of the big three firms, jails and prisons are granted a share of the profits through “site commissions.” And there’s plenty of profit to go around. According to a 2014 report on the nation’s prison system finances from the Ella Baker Center, approximately one in three families of the incarcerated going into debt simply to cover the cost of communicating with an inmate.

“The people this punishes aren’t the inmates. The people it’s punishing are their families and their kids, and those people haven’t done anything wrong,” says Bernadette Rabuy, senior analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) and co-author of Screening Out Family Time, PPI’s January 2015 report on the rise of video visitation in America’s correctional facilities. In the two years since Rauby released her findings, she says little has changed.

“You can’t think of this as Skype for inmates,” she says. “Sometimes the companies do a great job putting the cameras together, sometimes it’s a shoddy job. Over and over again you hear stories about connections being dropped, people that can’t understand each other, cameras that don’t work. And this is all time they have to pay for. If you’re home and you paid for 30 minutes for your child to talk to their father and it doesn’t work, you’re just out of that money and that time.”

In December 2016, Rep. Tammy Duckworth (D-Illinois) introduced the Video Visitation in Prisons Act, a bill that would require the Federal Communications Commission to amend its regulations to cap rates charged by service providers, prohibit flat rate, and address video quality standards. The ambitious bill would address many of the current issues with video visitation. It would require the Bureau of Prisons to ensure it doesn’t supplant in-person visits and that privacy is maximized in the video areas and equipment. The bill failed to pass last session and must be reintroduced, something Duckworth’s office is now preparing.

“Preserving contact with family members can enhance rehabilitation and improve the odds that former prisoners are able to become productive members of society upon their release,” Rep. Duckworth said in a statement, “and my new legislation will help reform our criminal justice system to make that easier—not just for prisoners, but for their families as well,” Rep. Duckworth said in a statement.”

For now, with both tech firms and correctional facilities collecting fees regardless of the experience, and with families given no choice in service providers, the quality of the experience seems unlikely to change. “There really is no incentive for the companies or the jails to make sure the technology works properly,” Rabuy adds. “It’s not like the family can take their business to someone else.”

Corrections officials argue video visitation is an effective means of curbing contraband.

Richard Van Wickler is the superintendent of New Hampshire’s Cheshire County Department of Corrections, but his credentials extend beyond incarceration, serving on the board of directors of the state’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and as chairman of the board for Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, a nonprofit organization of criminal justice professionals with a mission “to reduce the multitude of harmful consequences resulting from fighting the war on drugs.”

Van Wickler’s Cheshire County Jail held an average daily population of 174 in 2016, with a maximum capacity of 230 offenders staying an average of 55 days. Family, friends, and attorneys using video visitation to reach Cheshire County’s inmates only pay for the service if they use it offsite, and the few who do have rung up enough costs to generate $2,100 in “site commissions” in 2015, the most recent year Van Wickler has complete numbers for.

“When we built our new jail, we had a video system that was awful,” Van Wickler says, though he was unable to name the company that provided it. “Then we had bottleneck, and then we had dropped connections and all of those troubles. I took our business to Securus, and they have been 100-percent professional about making sure the services work. If the jail’s superintendent is doing their job to make sure the services work, this should not be an issue. And if someone is spending a 30-day stay in jail, this should not be a hardship.”

Van Wickler insisted that the services had also cut down on the amount of contraband smuggled into his jail, even compared to visits separated by protective glass.

“The majority of people in jail are not bad people, but they did get into bad situations,” he says. “But there are a small percentage who are cruel and opportunistic and even evil, and they will find ways to bring in contraband.”

Van Wickler’s experience may be an outlier. Though Cheshire County has yet to complete a review of visitation rates and contraband smuggling comparing figures before and after visitation, at least one Texas jail has, drawing far different conclusions. A 2015 Travis County Texas review found that as most in-person visits were done with the benefit of a glass barrier, there was little reason to believe that inmates were smuggling anything more or less efficiently when denied face-to-face contact. That’s if the inmates actually see their families. An inmate’s number of visits actually decreased on average after the jail installed Securus’ cameras. With 151 surveys and a review of visitation logs both before and after the introduction of video, the Travis County Sheriff’s Office found that visits were highest with a mix of both in-person and video offerings, with 1,429 more visits per month than were logged when video visitation was the only option.

“When you’re driving all the way to see someone, you expect to at least see them through the glass,” says Michael Cortz, 19, of Pleasant Hills, California. Cortz was able to visit his brother Lorenzo in prison and see him through safety glass for 18 months before he was transferred to a jail using video. “You see them on a computer it’s like, ‘What the hell’s the point? I drove 45 minutes for this, and I can do it at home.’ But then at home, you have to pay. So it puts you in the mindset of, ‘Why do I do this?’”

There’s a good reason for society to prefer that Cortz makes the trip. Multiple studies, including a report from the Vera Institute of Justice, have found that the greater an inmate’s connection with family while behind bars, the lower their risk was to reoffend.

Ironically, it’s America’s prisons, holding our more dangerous offenders, that have been far slower to phase out in-person contact. Rabuy, the Prison Policy Initiative analyst, says that video visits seem to be far more popular with jails in part because local facilities are under more pressure to cut costs than state facilities, and the comparatively transient nature of their inmates makes installing the systems an easier sell.

It’s a small comfort for Toki that her husband has been moved to Ironwood State Prison to serve the remainder of his four-year sentence—even if it is a nine-hour commute.

“At least when I get there,” she says, “I’ll be able to see him.”