Opinion

Aokigahara, better known as the “Japanese suicide forest,” recently went viral after YouTuber Logan Paul recorded a video that apparently depicted a dead body hanging in the middle of the woods. Paul quickly faced backlash for the insensitivity of the clip, and he later apologized multiple times in light of the incident. But Paul isn’t the only one trivializing suicide victims’ struggles. Google’s page for Aokigahara is filled with suicide jokes.

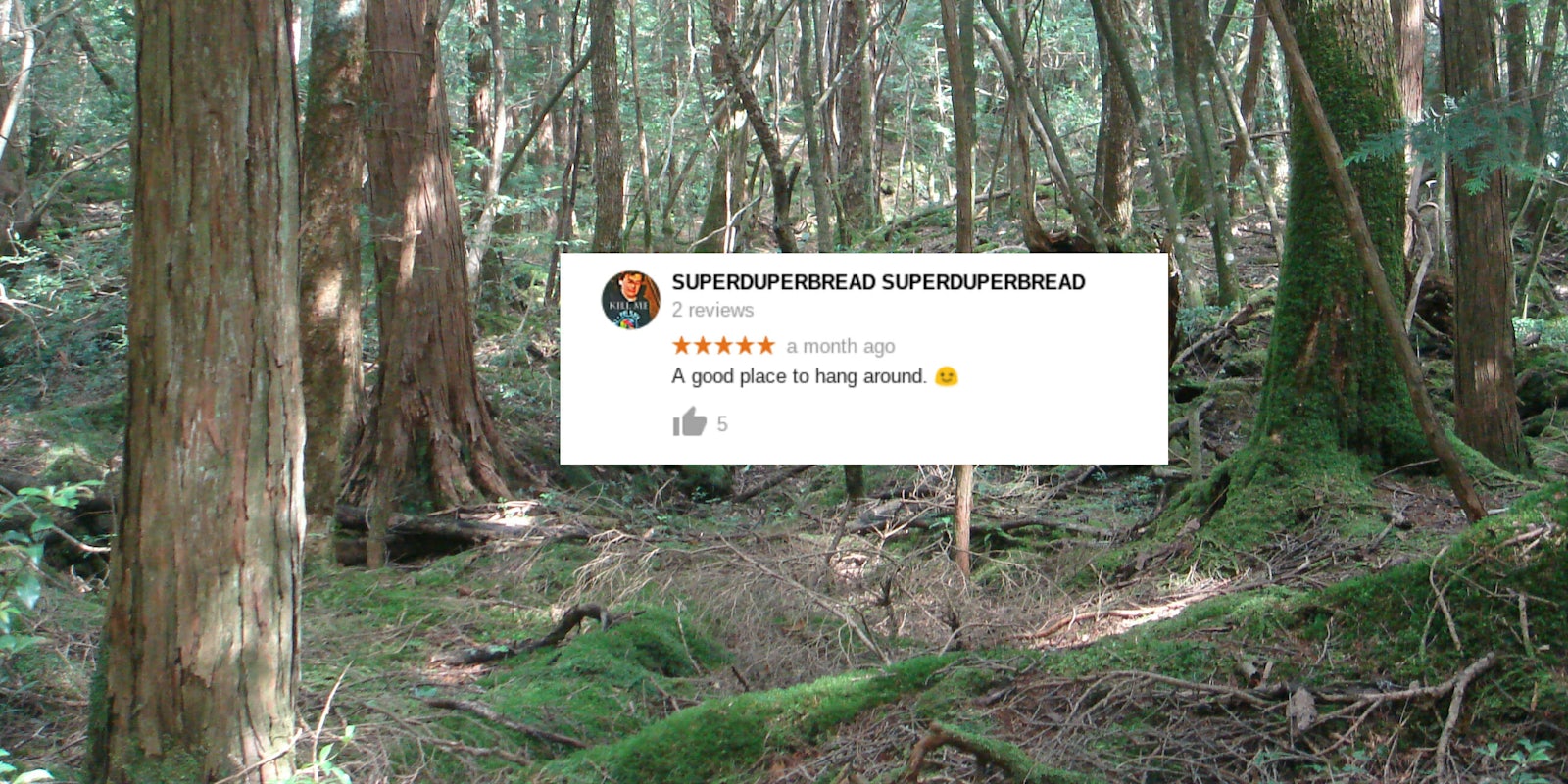

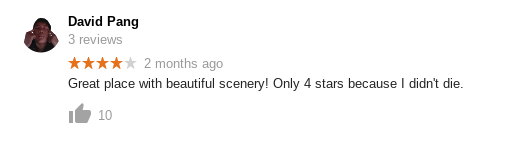

On Google Maps’ listing for Aokigahara, over 700 reviews are written about the forest, many of which praising its beautiful scenery and serene nature. But others make fun of Aokigahara’s reputation for suicides, with users joking about dying, killing oneself, or stumbling across dead bodies.

“Lovely Place, Nice atmosphere the staff were LOVELY!” one user jokes. “Offering cyanide to us and even the kids! The whole family had fun!”

Most of the reviews use Google Maps’ built-in rating system in a tongue-in-cheek way, acting as if stumbling across a suicide victim’s body is part of the experience. In one case, a poster left a 5-star review, claiming he had “absolutely great fun” while looking at the forest’s corpses.

“I’ve had no more fun looking at all the bones and corpses,” that poster wrote on Aokigahara’s page. “It gives you a feeling to be happy to be alive.”

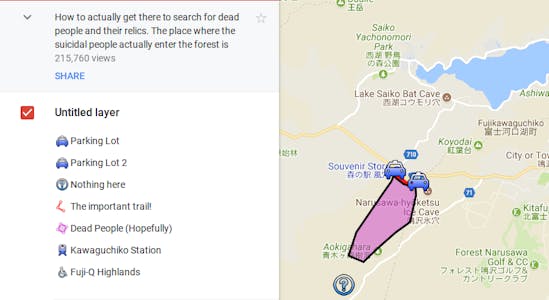

It’s not just Aokigahara’s review section that has users making fun of suicide. In the location’s “Questions & Answers” section on Google Maps, people regularly ask about the forest’s reputation for suicides, including whether people can still see dead bodies in the forest. This may be well-intentioned, but it’s worth pointing out that the forest has long been a tourist and school-trip destination for its grand beauty—12 square miles of hardened lava, featuring a year-round ice cave, breathtaking greenery, and wildlife. In one Google My Maps guide with over 200,000 views, a map encourages tourists to check out “Dead People (Hopefully)” by going off into the woods, therefore turning suicide into a tourist spectacle for Westerners.

“How to actually get there to search for dead people and their relics,” the guide begins. “The place where the suicidal people actually enter the forest is south off the hiking trail which connects two local caves.”

When asked about the troubling posts, a Google spokesperson told the Daily Dot that the platform lets users contribute to Google Maps as a means to “enhance the user experience.” “We go to great lengths to make sure content published by third-party contributors is useful and reflects the world our users explore,” the spokesperson said. “We reserve the right to remove content that violates our policies or terms of service and to suspend or delete abusive accounts. If a user finds a review that is believed to be in violation of our policies, it can be flagged for removal.”

Suicidal people, and the complex struggles that can cause people to feel suicidal, are taboo subjects in the West. So much so, our discomfort with death and mental illness leads many to use suicide as a punchline or for shock value, instead of unpacking the factors that contribute to suicidal ideation and behaviors. But in light of Paul’s actions inside Aokigahara, it’s impossible to brush off the insensitive posts scattered across Google as a few bad eggs that haven’t yet been flagged. Clearly, the service has a problem with how reviews are monitored.

That’s in part because of—and made worse by—Google’s endless content and reach. It isn’t just a search engine; it’s also a tool for navigating everyday life. And that includes planning vacations, navigating historic landmarks, and researching peoples’ favorite locations. In fact, 69 percent of Americans prefer Google Maps over other apps, according to a recent survey, with at least 1 billion users regularly clocking into the app each month.

It’s easy to see how a person impacted by suicidal thoughts and behaviors could accidentally stumble across suicide jokes while using Google Maps—especially since the CDC reports that 1 million adults attempt suicide every year, with suicide serving as the second leading cause of death in 15 to 34-year-olds in 2015.

Ultimately, trivializing suicide stigmatizes people who are dealing with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, encouraging them to keep their suicidal feelings to themselves instead of seeking help. As Suicide Awareness Voices of Education points out, making light of mental health concerns ultimately alienates people who have them. In reality, suicidal people need help in order to get better, and that means they need unconditional care and support. Not edgy jokes.

“It’s actually demeaning to those with true illnesses that can’t easily stop these behaviors,” SAVE’s executive director, Dan Reidenberg, told HuffPost in 2016. “If we trivialize them into something else or we make that become the person’s identity, we have done everyone a disservice.”

https://twitter.com/flavordays/status/948061417512386560

https://twitter.com/tunahater/status/948073948712972289

https://twitter.com/_chloi/status/948033273107582976

https://twitter.com/nerdyasians/status/948034498704240642

On social media platforms like Google Maps, public comments impact others. Not only do they shame those with suicidal thoughts, they can help cause “suicide contagion,” where “exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviors within one’s family, one’s peer group, or through media reports of suicide” causes “an increase in suicide and suicidal behaviors,” according to the Department of Health and Human Services. In other words, there’s a medical basis for suicide talk triggering suicidal thoughts and behaviors in high-risk people.

Which means it’s impossible to mention suicide contagion without discussing the internet’s influence. A study from late 2017 suggested teens who spend a lengthy amount of time online show an increase in their risk for suicide proportional to their internet usage. Meanwhile, in a report for Newsweek from 2016, an expert with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention warns tributes to young suicide victims online may inspire more young Americans to take their lives. If Google wants to make sure its platform is a responsible one, then it needs to deal with invasive comments as soon as they appear.

This isn’t to say that it should be washed over that Aokigahara is a common destination for suicide in Japan; the country’s larger struggle with suicide is definitely worth pointing out. But there’s a difference between respectfully talking about an area’s issue with suicide and joking about it. And Google could take more steps to help users comfort, not ridicule, people dealing with suicidal thoughts.

While the platform has been good to offer the phone number and an online chat feature through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, it could also link to additional resources for preventing suicide. That includes giving advice for helping loved ones comfort suicidal people and recognizing warning signs for impending suicidal behavior.

Letting users create guides to finding dead bodies is inexcusable—and so is ignoring fake reviews. Preventing suicide starts with managing what kind of content is posted and how it’s shared. Otherwise, services like Google shouldn’t be expanding without moderators in place. Such irresponsibility could lead to irreversible harm.

For more information about suicide prevention or to speak with someone confidentially, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (U.S.) or Samaritans (U.K.).