Michael Pinsky met Vaidhy Murti during his freshman year at Princeton University at a baseball game. The two became friends, and have remained so throughout college. But they knew that not everyone is so lucky. Between dorm drama, exhaustive hours of studying, and general stress of being a “young adult,” upper education can be a difficult place to foray into real friendships.

“We realized that things don’t always happen that way,” Pinsky said of the friendship that developed with Murti, a computer science major. “We wanted to create an easier way for college kids to branch out of their social circles a little more—kind of a risk-free way to reach out on your campus.”

From that first meeting and brainstorming sessions that followed, Pinsky and Murti, now both seniors, created Friendsy, a service that lets college students anonymously connect with each other. When two people who have been matched mutually agree to meet each other, the identities of both parties would be revealed.

“The original idea for Friendsy was to use a .edu email address to create an account and immediately only place you in a network with other people from your school,” Pinsky told the Daily Dot. “So only Princeton people can see other Princeton people, for example. From there, you can click on different buttons for different levels of interest: classmates, friends, hookups, and dates.”

“The original idea for Friendsy was to use a .edu email address to create an account and immediately only place you in a network with other people from your school,” Pinsky told the Daily Dot. “So only Princeton people can see other Princeton people, for example. From there, you can click on different buttons for different levels of interest: classmates, friends, hookups, and dates.”

The app launched on Princeton’s campus in May 2013 and within the first week, attracted 1,000 members, a fourth of Princeton’s campus.

Now, Pinsky says Friendsy has 20,000 registered users at 40 college campuses in the United States, 11 team members, and a myriad of campus representatives at participating schools to help spread the word about the website and app.

Friendsy is not a singular example of apps developed by college kids for college kids. Collegiate entrepreneurship and app development courses and programs allow students to create a variety of businesses geared toward their peers.

StatusOwl, an app created by former University of Michigan students, also caters to just the student body. With the app, which launched in August, users post and follow real-time information about bars and parties in the area.

“We’re a real-time guide for nightlife,” cofounder Akash Jobanputra told The Michigan Daily. “Everyone can go to StatusOwl and see what’s going on and honestly make decisions about where they’re trying to go.”

To get the word out about their app, the StatusOwl team markets themselves at local bar events and student groups on campus, working to build their network in the immediate area rather than a widespread sample of people and keeps out the troves of parents, grandparents, and other adults that have penetrated oversaturated networks such as Facebook.

Breeding grounds for creativity

At Michigan, events such as an annual 48-hour hackathon foster an environment for students to create products that go beyond the confines of a classroom. The hackathon, first hosted in 2010, calls for teams of students to work on an idea over the course of a weekend. Elliot Soloway, an Arthur F. Thurnau professor at the University of Michigan, said that the first hackathon drew between 30-40 people. In comparison, the fall 2013 event garnered 1,000 students and community members and was hosted at the football stadium.

Soloway pioneered the hackathon, which has since been taken over by a student-run organization, U.M. Mobile Hacks. Soloway instead has turned his energy toward helping those who take his mobile app development course, which was first offered the same year that the hackathon began.

The class has a similar premise to the hackathon, except instead of 48 hours, students have an entire semester to develop an app idea. First, each student pitches a concept to the class. A second presentation shortly after gives students a chance to refine their pitches and propose their ideas again. After that, groups of three are formed, and each group spends the remainder of the semester building. Soloway creates various presentation deadlines to explain the design of the app as well as show a minimum viable product. And in order to get an A in the class, Soloway requires that the app be available for download in the App Store.

Though Soloway hadn’t heard of StatusOwl, he’s excited to see how his students and others at the University of Michigan have taken interest in mobile apps, a subject that captivated him when he became enamored with PalmPilots. “They were really the first handheld mobile computer,” he explains.

Solway, a computer science professor, has geared his class toward computer science majors but hopes one day to be able to work with other disciplines, such as business or design, to allow students to learn more perspectives when it comes to creating a product and marketing it to audiences. This month, the University of Michigan’s entrepreneurship program earned the number 18 rating in Entrepreneur magazine.

During the first year of his class, one of the teams created an app called the DoGood app. “All it did was it said, ‘Well, what do you want to do good today?’ And you’d say, ‘I want to hug my mother,’ and it would post it somewhere on a website, and someone else would look at it and say, ‘yeah, I want to do that too,’” Soloway said. That app later sold for six figures.

Another app that got its start in Soloway’s class was acquired by the university’s Technology and Information Services and further developed into what is now the institution’s main app for sharing news, contact info, campus maps, and bus routes.

Solway estimates that 90 percent of the apps created, however, never make it past the end of his semester-long class. He compares the process to making pancakes. “The first pancake is very ugly, but you’re testing the griddle, you’re testing the batter, you’re getting going,” he says. “That’s what’s happening in my class: It’s the first pancake, and it’s not really pretty.”

Students and safety

For Pinsky, Murti, and the rest of the Friendsy team, their first dive into app development has been a successful one.

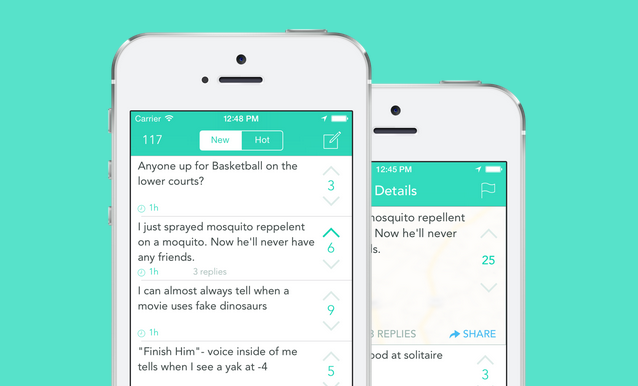

The Friendsy team since expanded from the service’s first iteration based heavily on user feedback. They came up with Murmur, an anonymous feed that allows students to post anonymously for the community to see. A person can compliment someone else, post about something they’ve overheard on campus, or share a photo that they took. The feed is monitored by the Friendsy team in order to weed out any offensive or inappropriate content.

Meanwhile, Yik Yak, an app created by two now-former students at Furman University, in South Carolina, has received negative backlash for its uncensored feed of anonymous comments. The app was intended to serve as a means to gossip about what’s going on around within a certain radius of a person’s current location (presumably on a college campus), but some comments have contained racial slurs and violence threats. The app has even caught on in high schools, moving some schools to ban usage of the app altogether.

YikYak

But since membership to Friendsy is restricted to those with a campus email address instead of proximity, users can rest assured knowing that the comments are coming from a real person at their college. “The worst thing you can happen to you on Friendsy is that you like someone who doesn’t like you back,” Pinsky said.

The murmur feed, as well as the apps, were mostly developed over the course of this past summer at Princeton’s Keller Center eLab program. The program grants access to mentors and advisors to students as they develop their companies. Created three years ago by Cornelia Huellstrunk, associate director of the Keller Center, and Sanj Kulkarni, former director of the Keller Center, the eLab arose as “a direct response to the growing interest of Princeton students in the area of entrepreneurship.”

“When I first met with Friendsy, I was struck by the passion that the two founders … have for their venture and entrepreneurship as a whole,” Huellstrunk, who also directs the eLab program, told the Daily Dot in an email. She considers Friendsy one of the more successful startups to emerge from the program, along with Duma and Firestop, and she says that over half the alumni from the past three years are still working on their startups.

While tech startups such as Friendsy greatly benefitted through participation in the program, Huellstrunk feels that what makes the eLab so unique is its openness to anyone with an idea. “In contrast to many profit accelerators, Princeton University’s Keller Center eLab program is technology agnostic and hence open to ventures of all kinds, both high tech commercial and social, as well as software and hardware,” Huellstrunk said.

Pinsky and the Friendsy team hope to attract 100,000 users as soon as possible. They’ve also just posted their first round of outside funding, which they’ll use for quicker servers as well as more campus representatives. But as they continue, Pinsky says that mission of Friendsy remains at the heart of the product. “I guess you can call it a part dating app, but it’s also a way to make new friends and stay up to date on what people are talking about and just overall be happier,” Pinsky said. “It’s really geared toward happiness.”

Building the next Facebook… or an anti-Facebook?

College campuses, with a highly concentrated population of young adults, provide a sort of unique testing grounds for new companies looking to test their product. Businesses such as Friendsy have centered their businesses around one audience instead of trying to reach out to masses of people, much in the way Facebook did on college campuses before becoming the synonymous social network we know today.

Friendsy, however, wants to keep up these small networks, and Pinsky feels that Friendsy has brought back the trustworthiness and exclusivity of a service available only to college students. In comparison, StatusOwl aims to connect the University of Michigan, while one of the most successful apps originally created in Solomon’s class is one that catered its platform to providing information pertinent to Michigan students.

By creating a college-centric network of users, those apps intend to allow their users to make more of an impact in their social networks. They also immerse themselves into a market of people equipped with up-to-date technologies. The Pew Research Center found in January that 83 percent of young adults age 18 to 29 own a smartphone, the highest rate of ownership out of any age group.

Meanwhile, Facebook usage among young people aged 18-24 has decreased slightly as the number of adult users increases. A report published by researchers at Princeton University claimed that 18- to 24-year-olds have been abandoning Facebook at higher rates than older demographics and predicted that Facebook will lose 80 percent of its users by 2017, explaining that the social network has already reached its peak popularity.

While the assertion will not likely come to fruition, young adults could begin spending less time on Facebook exchange for smaller networks. And as long as colleges continue to create opportunities for their students to thrive and as long as students continue to search for ways to improve their lives and their peers’ lives, then apps propelled by higher levels of exclusivity just might make a comeback.

Photo via COD Newsroom/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)