Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers threw five touchdowns in his team’s Week 3 victory against the Chiefs. He completed a solid 68.8 percent of his passes for 333 yards, and he didn’t toss a single interception. Rodgers is the best quarterback in the NFL right now, and that game was his best of the season.

But when fans logged onto ProFootballFocus.com the next day to view the grade the PFF analysts gave him, they must have been shocked by what they found. Analyst Ben Stockwell—the man who watched the game, analyzed every player on every play, and gave each his own separate grade—wasn’t impressed by Rodgers’ performance.

In fact, Stockwell gave Rodgers a negative grade. A negative grade even though Rodgers had tossed at least five touchdowns in a game for only the fourth time in his 11-year career. A negative grade even though Rodgers seemed nearly perfect.

An outcry soon arose on Twitter.

In a result obvious for everyone who watched #Packers QB Aaron Rodgers last night, he scored a -2.3 rating from @PFF pic.twitter.com/C3b5o9AS3M

— Ian Rapoport (@RapSheet) September 29, 2015

Immediately, PFF sprung into action. Stockwell wrote a piece on how he formulated Rodgers’ grade and explained that three of the five touchdowns Rodgers threw really should have been credited to receiver Randall Cobb, who did most of the hard work to get himself into the end zone on those plays. Stockwell also pointed to Rodgers’ fumble midway through the second quarter and a couple of bad passes that were graded negatively.

Stockwell insisted that nobody at PFF believed Rodgers had played a poor game. But he also wrote that if you looked at Rodgers’ entire performance in context, you’d find that it was only adequate and not quite so wonderful.

Wrote Stockwell: “But for a couple of poor plays, his overall grade would have matched the sort of grade that you would be expecting to see from him, but those poor plays, coupled with the relative ease of some of his scores mean his performance last night was far closer to average than it was to the fantastic performance the box score suggests. The context surrounding his grade is crucial.”

Many readers, though, didn’t buy the explanation.

@joshkatzowitz @PFF Keep giving out pluses and minuses while Rodgers keeps playing the position better than I've ever seen. Absolute joke

— DonkeyDong (@davegardner70) September 29, 2015

https://twitter.com/aaron_korber/status/648865473950453760

@PFF_Ben the proper context is your system is trash

— Beñ (@brnt2470) September 29, 2015

And from a respected Philadelphia Eagles beat writer…

This is why anyone that cites PFF's "grades" is an idiot. https://t.co/qfaykLkuuV

— Jeff McLane (@Jeff_McLane) September 29, 2015

That’s incorrect. No, you aren’t an idiot if you cite PFF’s grades. The website has been logging games full time for seven years. The innovations it’s made in how to watch football and the niche in the NFL universe it’s created and filled cannot be understated.

Nineteen NFL teams spend large chunks of money to work with PFF (the website and an AFC team official who uses the services declined to tell the Daily Dot how much) and to use the immense data it provides. At some point in the future, it’s probable that most, if not all, NFL organizations will be working with PFF.

PFF is for the smart football fan and certainly not for the idiot. The Rodgers grade might have seemed way off—and after the tape of the Week 3 game was reviewed a few more times by the site’s analysts, that negative number eventually was changed to a +0.9—but PFF, in recent years, has become one of the most useful entities in the NFL.

“They work hard, and they provide a good service,” CBSSports.com NFL writer Pete Prisco told the Daily Dot. “I don’t agree with their grades. I never will. I do my own stuff, and I’ll go back and look at their grade and ask what the hell they were watching. But their data is fantastic. How does the ball come out? How many blitzes did that team run? What did they do on all the third-and-longs in that game? But providing a grade for a player for every position is darn near impossible.”

And as Stockwell was reminded in Week 3, getting everyone to agree that the grade is correct is an exercise in futility. Yet the fact that Pro Football Focus has become so important to so many people and to so many teams in the span of a decade is an immense accomplishment, especially in the world of the NFL where outsiders and innovations oftentimes are denied entry.

The site began analyzing every game and every player during the 2008 season, but PFF’s founder Neil Hornsby originally had the idea in 2004 when, after watching TV commentators discussing the players they thought were the best in the league, Hornsby thought to himself, “Really? That doesn’t seem right.” To prove himself correct, Hornsby created a database and began combing over each game play by play to determine if he could assign objective numbers and statistics to what was happening on the field.

This data is valuable to everybody—to teams, to agents, to the general public.

From there, the operation grew. Hornsby, an Englishman who didn’t attend his first football game until he was 42 years old, hired Stockwell, a fellow Englishman, and then Sam Monson, an Irishman, to help him log games and put together the website that has impressed NBC analyst and former Bengals star receiver Cris Collinsworth so much that he significantly invested in the site before the 2014 season.

They weren’t simply watching the quarterback throw to the receiver and then watching the receiver get tackled by the safety. They were much more specific than that. As the Wall Street Journal explains, “Pro Football Focus was also keeping track of even more advanced data, that it hoped to sell to media outlets and, perhaps, football teams. For a pass play, it didn’t merely record who threw it, who caught it and how many yards were gained after completion. It kept track of how many seconds elapsed before the quarterback released the ball, where each player stood at the start of the play, which defensive player applied pressure, and which blocker allowed it.”

Said Monson to the Daily Dot: “This data is valuable to everybody—to teams, to agents, to the general public. We were looking at all these different avenues.”

First, though, Hornsby and company had to determine a grading system. Hornsby funded the venture out of his own pocket with the idea that PFF could sell subscriptions to the public who would be interested in seeing objective numbers for a player’s performance. At its max, about 10,000 fans have subscribed to the service.

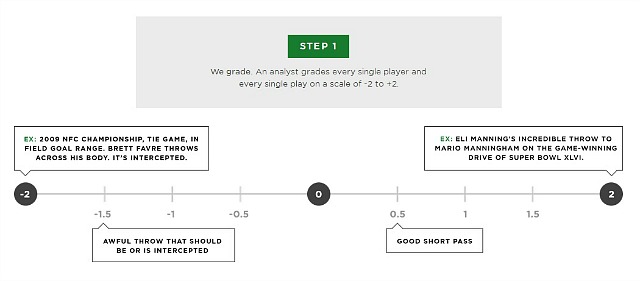

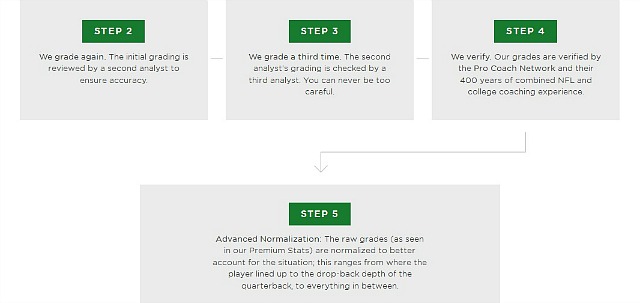

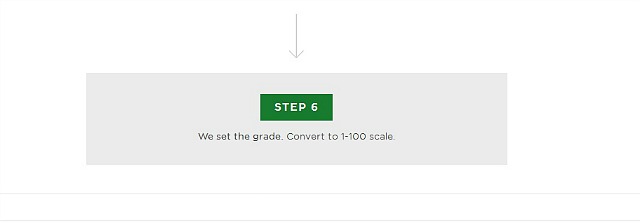

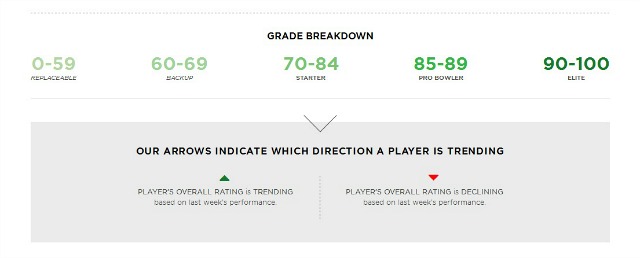

Here’s how the grades are formulated, the same system used by Ben Stockwell when grading Aaron Rodgers in Week 3.

For each game, two analysts break down the film. One determines the player participation on each play. (For example, which player lined up where and did he blitz or drop into coverage?) One works out the advanced data. (Did the right tackle get beaten inside and what grade does he get for his mistake, how was the quarterback’s throw, and how many yards did the receiver gain after he caught it?)

The analysts, which are based in this country and in the U.K. and Ireland, begin their work Sunday as soon as the 1pm ET games are complete. For the 4pm ET games, which end about midnight in England and Ireland, analysts will start working until their eyelids begin to close on their own, take a few hours to sleep, and then wake early in the European morning to finish their work. By 6am ET on Monday, the first run through on each game is complete and grades are posted.

By Wednesday, the additional checks and verifications are finished, and the week from before officially is done.

But as one might expect, the site also faces criticism—unless a PFF analyst is embedded in a team’s meeting room or in the press box with the assistant coaches during the game, it’s impossible to know each players’ goal for each play. PFF can figure out what happened, but the site can’t know what was supposed to happen.

“In some cases, even the coaches don’t know all the assignments for a play,” Prisco said. “From that standpoint, it’s unfair to the player… Their data is fantastic. They’ve made a nice niche of it. But people think it’s the Bible. I respect them and I use them to cross-check stuff, but I wouldn’t say it’s the Bible of player grading.”

Prisco has talked to a number of former offensive linemen—well-respected figures like seven-time Pro Bowler Steve Hutchinson, five-time Pro Bowler Tony Boselli, and two-time Pro Bowler LeCharles Bentley—and not even they know the offensive line assignments of the film they’re analyzing. Yet, PFF can give a certain lineman a minus-2 grade on the play but never really know for sure if the failure was actually that player’s fault.

Monson thinks that criticism is a lazy one.

“If you look at a play long enough and you work it through player by player, it’s usually not difficult to work out what a guy was trying to do,” Monson said. “The more you know about a particular offensive and defensive scheme and what guys are supposed to be doing, it makes it easier… We tend to get most of those tricky ones right.”

PFF, though, knows there are plays where the grade might be tabulated incorrectly simply because the player’s assignment is unclear. But the site set the grading framework in a way that the analyst doesn’t need to know everything about a play that was supposed to occur.

PFF doesn’t guess. Instead, the analyst grades the player on what he accomplished on the play and not what his coaches necessarily wanted him to do. And remember, PFF actually gets NFL feedback on the backend of the grading process to help correct whatever error might have been made in the initial analysis.

“We’re not trying to work out what he was supposed to do. We only grade what we can accurately see,” Monson said. “There will be plays when a guy blows his assignment and completely goofs but makes a good block on a linebacker and we’ll give him a positive grade for that. His coach in the meeting room is going, ‘That’s a terrible play. It’s a mental error, and we’ll downgrade him heavily.’ It happens, but when you work out 60 plays in a game and thousands of plays in a season, it’s an extremely small percentage of his overall grade.”

The Rodgers’ grade might have been an outlier—at least in the eyes of the fan who woke up that Monday morning and couldn’t believe that the Packers quarterback had received a negative mark.

As soon you start doing that, you’ve completely torpedoed your integrity even if far fewer people can see that

When he was analyzing the Packers-Chiefs game, Stockwell realized early on that the grade Rodgers was earning was not going to match the stats and the general perception that Rodgers had put together a phenomenal performance. But Stockwell also wasn’t worried about the reception he might receive after the grade posted (though Stockwell admitted he wasn’t aware he would get so much heat).

“You can never worry about the reception of an overall grade and let it affect how you grade individual plays,” Stockwell told the Daily Dot. “Because the whole system is based off a play-by-play grading system, the grade for each individual play has to stand up to interrogation in isolation. It would do us more damage and would be dishonest to fudge the play by play to make the final grade ‘feel right.’ …As soon you start doing that, you’ve completely torpedoed your integrity even if far fewer people can see that than the overall grades that go on the site and social media.”

And for PFF, that integrity—the site’s credibility, in fact—is important. But the site’s analysts have to look at the entire picture, and Rodgers’ stat line—the five touchdown passes, the 333 yards thrown—wasn’t the whole story. The grade isn’t settled simply by watching the highlights and the lowlights of a performance.

It’s everything in the middle, the everything that was forgettable. Those plays—everything that was non-spectacular to the fan not paying close attention—are often what make up the bulk of the final grade.

Still…

@PFF loses all credibility if they gave Aaron Rodgers a negative grade from last night. You can keep those fucking metrics.

— Allen K. (@AllenK_81) September 29, 2015

“If we’d actually lost all the credibility that people have told us we’d lost over the years, we wouldn’t exist anymore,” Monson said. “As much as we want to appeal to the public and be respected, we’re also (working with NFL teams). Those are the guys that provide us with our credibility.”

And thrive, because as of this year, PFF has upped its NFL clientele from a dozen to 19. Monson thinks that eventually landing 30 of the 32 NFL teams is attainable, and for at least one team, it’s easy to see why: PFF simply makes life easier.

“I know they gained popularity from the public side with their game analysis, articles, and their evaluations and grades on players, but from the team side, the best part has been the amount of data they provide,” said one AFC team official who talked to the Daily Dot on the condition he could remain anonymous. “It’s almost like a quality control coach with the level of detail they have. There’s an incredible amount of value with the pure data they provide. The amount of increased efficiency in your weekly process, that makes it incredibly worthwhile.”

This team employee is using PFF for the first time this season, and he’s been amazed at the change. Before PFF, a quality control coach or an assistant coach would have to spend the bulk of his workweek breaking down the film of an opponent in order to study that team’s tendencies, schemes, and formations. But since PFF already has done that and since the site allows for that information to be integrated with the video service the team already utilizes along with the team-specific terms it uses for its personnel groupings and schemes, PFF saves the team innumerable hours.

“All of that manually had to be broken down by a coach last year. Now, it’s a click of the button,” the team official said. “They can break it down by any filter. You have the data at your fingertips. Before you subscribed, you may have had questions where you say, ‘I want to know XYZ, but before I can start to know X, I need to take 10-15 hours to chart this and organize the data so I can begin the analysis.’ Now, that work is already done for you. It frees you up to do this higher-level thinking instead of spending hours getting organized.”

If the team needs to know the most common route for an opponent’s top receiver, PFF has it covered. If a team needs to know how many targets a tight end gets on third-and-short situations, PFF has it covered. A middle linebacker’s success when dropping back into pass coverage, sacks occurring during defensive blitzing, a quarterback’s rating on play-action passing. PFF has all of it covered.

It’s why Monson believes PFF’s services, with one or two exceptions, will eventually be used all over the NFL.

Teams are now paying PFF plenty of money to ignore the sticker price and determine what’s actually under the hood. It’s why PFF is relevant and growing more so every single season. It’s why their credibility isn’t in question.

“It’s 19 teams and growing,” he said. “There might always be one or two teams that want to do it their own way, and there’s not much convincing them. But almost universally when we get to sit down with these guys and explain to the right people what we have, it’s a matter of time before they buy in.”

Some of the football public and much of the media who cover the league have done so as well, even if PFF’s authority supposedly took a minor hit because of the Rodgers grade. But the AFC team official can understand PFF’s rationale.

“That captures some of the disconnect from PFF to the public,” he said. “If you had actually broken down that game and even if you hadn’t come out the exact same way on Rodgers’ performance, you would probably see things pretty similarly. The broad numbers say this, but I can understand why the performance was not as impressive as the numbers would suggest. It’s sort of hard to grasp if you just see the sticker price.”

Teams are now paying PFF plenty of money to ignore the sticker price and determine what’s actually under the hood. It’s why PFF is relevant and growing more so every single season. It’s why their credibility isn’t in question.

“In any industry, there’s always going to be people who are more old-school, but whether it’s PFF or another data provider, it’s only a matter of time before it’s industry standard,” the AFC team official said. “You can make an argument that it already is. Even if you’re the most old-school person in the NFL, it only takes a few minutes to sit down to see what you have at your fingertips. After that, it’s hard to say why you wouldn’t use it.”

Photo via Mike Morbeck/Flickr (CC BY SA 2.0)