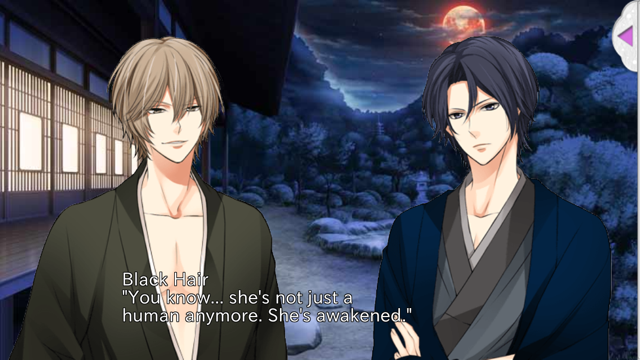

I am a shy Japanese librarian who lives a solitary life until two handsome strangers named Fox Eyes and Black Hair arrive at my doorstep. They have broad shoulders, impossibly high cheekbones, and the same hairstyle as the skater boys I wanted to make out with in eighth grade. Despite the outdatedness of their coiffures, and their obvious rudeness at showing up in the middle of the night, I find them both devastatingly attractive.

I don’t know this when I first meet them, but I have been born with a special, otherworldly power (what this power specifically entails is unclear) that renders me irresistible to special, otherworldly beings called “ayakashi.” Fox Eyes and Black Hair are such ayakashi, and they’ve come to inform me that I will be destroyed unless I give up my special power to one of them in the form of a kiss.

To an American feminist, a narrative centering around a weak-willed female protagonist swept off her feet by a mysterious, verbally abusive, floppy-haired stranger sounds ridiculous, if not outright offensive; it also sounds like the plotline of a mediocre True Blood spec script. Yet this is the story behind Enchanted in the Moonlight, an enormously popular English-language romance simulator from Japan.

Enchanted in the Moonlight is an English-language version of a game by the company Voltage, Inc., which creates virtual dating and romance apps that are extremely popular among young Japanese women. (They’re also the team behind My Forged Wedding, a virtual narrative where you’re literally forced to enter into a sham union with a mysterious stranger.)

Like Enchanted in the Moonlight and My Forged Wedding, most of Voltage’s games feature shy, weak-willed female protagonists swept off their feet by eerie, verbally abusive, high-cheekboned androygynes. There are no non-heteronormative relationship options, nor is there the possibility of your avatar having sex with any of her suitors. When you play these games, you sort of get the sense they were authored by a 14-year-old girl who regularly writes steamy Divergent fan fiction, but has never actually talked to a boy in her life.

Yet Voltage is enormously popular among young women in Japan and elsewhere, with more than 22 million people playing their games worldwide. Now, with the release of the English language version of Enchanted in the Moonlight and the action-thriller romance app Queen’s Gambit in August, their ninth original US app, Voltage hopes to bring virtual dating apps to a North American market.

“We feel this is an ubiquitous genre,” Voltage CEO Yuki Tsutsami told me while appearing at the Anime Expo in Los Angeles earlier this month. “It is a genre that appeals to all women not just in Japan but all across the world, and we feel that creating global applications will fulfill the needs of women worldwide.”

The question is, though: Will these somewhat esoteric, dime store paperback-esque virtual narratives translate to an audience of North American women? To answer this question, and to understand the appeal of virtual romance apps in general, we have to take a step back and look at the genre from which they arose.

My Forged Wedding and Enchanted in the Moonlight are examples of otome games, a genre of dating sims targeted at young Japanese women that emerged in the mid-90s, around the time that mobile gaming started to catch on in Japan. They’re an outgrowth of eroge, or erotic games, particularly erotic games for men.

“Around the 1980s and 1990s there was a boom in computer and portable gaming console games aimed at men that were dating simulators,” Cathy Y., an environmental lawyer in Houston and an avid player of Japanese games, explained to me via Gchat. “The whole idea would be that you would woo girls, there would be multiple girls, each with their own ending, and if you played it correctly, you could often end up in having sex with them in the game.” She sees otome as a female-oriented outgrowth of that phenomenon.

Otome games feature a wide range of different scenarios—some take place in high schools and apartment buildings, while others like Enchanted in the Moonlight have more supernatural themes. But their general structure tends to be pretty consistent. “You usually play as a given female character (the ‘heroine’ I guess), and are put in a scenario with a variety of attractive dateable male characters,” Lucy Glasspool, a graduate student at Nagoya University who studies gender and Japanese RPG games, explains. Your primary objective is “to get together with one of these guys before the end of the game.”

Despite its roots in the eroge genre, Voltage’s games are pretty staunchly asexual. (There’s a separate sub-category of otome that are decidedly NSFW.) This is in part because the games are targeted at younger Japanese women, many of whom have probably not had sex before: “We want them to focus on the general romantic aspects, rather than the direct sexual aspects,” Tsutsami explains. Glasspool proffers another explanation: The lack of explicit sexual content in the games allow young women to “explore romantic/sexual themes in a ‘safe’” and non-threatening setting.

But contrary to the perception that the games are targeted exclusively at younger women, Tsutsami says many otome games are actually played older women: “Women who left high school 10 years ago, in their late 20s, early 30s.” That’s in part because Japan had a head start on the United States in terms of the mobile gaming market, with users starting to play mobile games in the late 90s. “Nowadays the ones who grew up playing games in the late 90s are adults themselves, so the companies now have two populations to advertise to: new young gamers and older experienced gamers,” Cathy says.

It’s the younger audience that Voltage is trying to reach in the United States, where virtual dating apps, let alone otome games, have not nearly caught on to the extent that they have in Japan. But the company will face a number of obstacles in that regard.

For starters, there are a number of tropes in popular otome games like Enchanted in the Moonlight that simply wouldn’t fly for an American market. “Otome games have a lot of the same tropes as manga or anime in Japan,” Cathy says, listing the megane (glasses) character trope popular in anime as one example.

The heroes of otome games, like the aforementioned Fox Eyes and Black Hair, also have different characteristics than their Western counterparts. “In appearance, I think the anime/manga ideal reflected in otome as to what the ideal guy looks like is very different than what we’re used to as a Western audience,” Cathy says. They’re usually far more androgynous in appearance; Fox Eyes and Black Hair, for instance, look more like One Direction band members than the rugged, Marlboro Man masculine ideal so popular in the Western cultural imagination.

But by far the most problematic trope associated with otome games, not to mention manga and anime in general, is the element of rape fantasy and non-consensuality, which runs throughout even SFW games like My Forged Wedding and Enchanted in the Moonlight. “I AM really uncomfortable with how much of eroge game and otome games depend on nonconsensual sex or flat out rape,” Cathy admits. “It’s a really common trope… Of course, if you’re dealing with the non r-18 (SFW) games, and it’s all dating and kissing or whatever, it’s less likely, but one of the tropes IS the villain who turns out to be the heart of gold or can’t resist having his way with you or whatever.”

Even if Voltage’s games don’t feature explicit, let alone non-consensual, sex, there is nonetheless something problematic about the gender dynamics at play in the games. The heroine in Enchanted in the Moonlight, for instance, is a shy, reserved, weak-willed librarian, who’s essentially putty in the hands of her more domineering male pursuers. Lucy Glasspool agrees that there’s very much a “damsel in distress” element to the majority of otome games.

“While Japanese pop media aren’t exactly devoid of strong, badass, positive-role-model type female characters, unfortunately they’re in a definite minority; the hyper-feminine, itty-bitty squeaky-voiced heroine is still very much in evidence, from the otome game girls to AKB,” she says. She speculates that the weakness of the female lead is perhaps intentional, “so that the player doesn’t have to pay too much attention to her as a character, [and so] she acts more as a kind of ‘shell’ for the player to inhabit,” but she admits the trope rubs her the wrong way nonetheless.

Tsutsami says that for the North American releases of Voltage games, the damsel-in-distress trope will be destressed, if not eliminated entirely, to benefit a Western audience. “We’ll have stronger female characters who are more independent and the men will be more masculine as well, instead of the more feminine archetypes,” he promises. The North American releases will also feature more locations that are familiar to Western audiences: For instance, while the Japanese version of one Voltage game takes place in Tokyo, the US release will be set in Los Angeles.

But it’s unclear exactly how these cross-cultural translations will go over with American audiences, particularly for pre-existing English-speaking otome fans, who already issue vociferous objections to the Westernization of the games on Tumblr: “I think it’s particularly important that the translations don’t try to localize out the ‘Japaneseness’ of the games, as it’s this element that a lot of fans find most attractive,” Blackpool says. Ironically, part of the appeal of a game like Enchanted in the Moonlight is how niche and specific it is to Japanese culture; otherwise, it would merely be another Twilight/True Blood fan fic crossover.

Cathy doesn’t predict virtual dating sims will become mainstream in the U.S. anytime soon: “I don’t really envision otome games becoming a huge thing, at least not in their current form,” she says. “It’s too tied to the Japanese anime/manga aesthetic.” Even if it weren’t, the concept of virtual dating apps, let alone supernatural or high-concept virtual dating apps like My Forged Wedding or Enchanted in the Moonlight, is foreign to Westerners who are just getting used to the idea that non-virtual dating apps like Tinder are a thing.

But Tsutsami says he’s confident that the themes explored in Voltage games are universal enough to have worldwide appeal. “We see [our games] as like a TV show that you would enjoy on your phone or your tablet instead, and we feel it’s definitely a growing genre,” comparing them to a soap opera or romance novel in interactive form. “There’s a definite market in America and worldwide.”

Screengrab via Enchanted in the Moonlight/Voltage Inc.| Photo via SecretSmile (CC BY-SA 2.0)