In the summer of 1948, Ben Stonehill recorded more than 1,000 songs—almost 40 hours of recordings—sung by Holocaust survivors. He recorded them in the lobby of New York’s Hotel Marseilles, where post-war Jewish refugees were being temporarily housed.

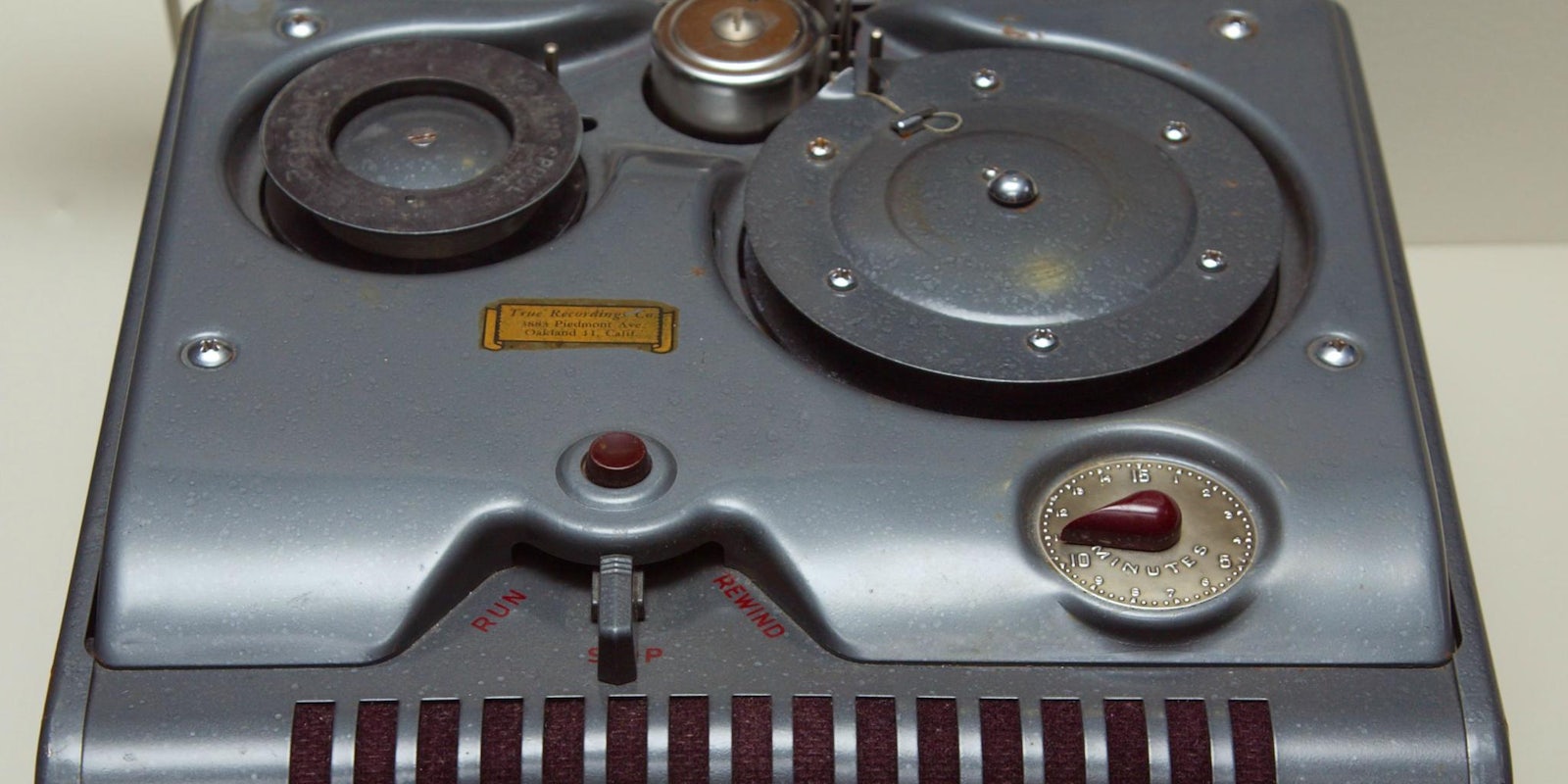

Stonehill was not an academic. He owned a New York flooring store but, inspired by Lomax, swung a deal to borrow recording equipment from an electronics store in exchange for promoting it. His goal was to track the sounds of Jewish life, some of which he feared were going to die of the wounds they bore from the war.

Reflecting the rainbow of nationalities expressed by the Jewish diaspora, and the scope of Nazi evil, the songs were sung in Czech, Hebrew, Russian, and Lithuanian. But as NPR points out, the majority were sung in Yiddish.

Now, thanks to the Center for Traditional Music and Dance, 66 of those recordings have been digitized and are available online, accompanied by English translations. Three-hundred more will become available over the next several months. In the coming years, as funding is secured, the rest of the recordings will be digitized and posted, Peter Rushefsky, the center’s executive director, told the Daily Dot.

In addition to the CTMD site, the songs are also available on the Stonehill Collection’s SoundCloud page.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum secured the recordings in 2006 from the Library of Congress and a host of other institutions where they were scattered. Miriam Isaacs, a sociolinguist who had a fellowship to work on the collection, subsequently approached the Center for Traditional Music and Dance as a partner to make the recordings public.

For many of the contributors, who had survived the greatest mass murder in history, recording technology was new. They wept, said Stonehill, when they heard their singing voices played back on his bulky wire recorder, knowing that what they had gone through would now be preserved.

Among the songs available are “England zugt tsu eretz Yisrul (England Says to the Land of Israel),” “Oy mame mame shlug mikh nisht (Oh Mom Do Not Hit Me),” “Fin di Varshever ganuvim (Of the Warsaw Thieves),” and “Mir zenen vi feygelekh fraye (We are Like Free Birds).” There are comic songs, songs about sex, God, socialism, and Zionism and a disproportionate number of songs about home and homelessness.

There are a couple of other collections of Jewish songs of more or less the same scale, but not the same scope. What distinguishes this collection is Stonehill’s exhortation to “sing anything you’d like.”

“There has been a lot of excitement over the release of the first 66,” said Rushefsky. “And I’ve received a number of emails from professional Yiddish singers from around the world who are eager to perform this repertoire, as well as folks working at universities, synagogues, and other institutions will be using the Stonehill Jewish Song Collection in their teaching and research.”

Before the advent of mass media, “folk songs were not just entertainment,” said Rushefsky, “they were used to record historical events, recruit for political movements and poke fun at aristocrats and religious leaders, in addition to expressing the loves, ambitions. and frustrations of everyday life.”

Their historical value is obvious. But so is their spiritual value. The culture of European Jews did not crumble to dust, as Stonehill feared. Like other cultures the world has found value in, some elements survived and time took others. Stonehill and his successors did their part to secure the survival of this part of it.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons