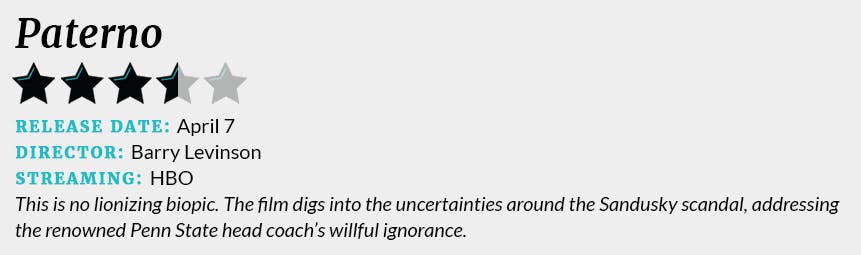

In Barry Levinson’s scorching HBO drama Paterno, a minor character asks a question that would seem rhetorical at the surface: “A crime against children happened. Why are we talking about Joe Paterno?” It’s a loaded question without straightforward answers, and the film dives into the ambiguities.

It does not attempt to traverse the life of late Penn State head football coach Joe Paterno (notably played by Al Pacino), instead choosing to chronicle two weighty weeks in the fall of 2011, beginning with the Nittany Lions squeaking by Illinois for the (then-record) 409th victory of Paterno’s illustrious career. It runs through the arrest of former longtime assistant coach and convicted serial rapist Jerry Sandusky, to the game after Paterno’s ouster.

Sandusky served under Paterno for 30 years starting in 1969 and was convicted on 45 counts of sexual abuse from 1994-2009 in 2012.

The base of the story centers around what occurred (or what didn’t) in the days after March 1, 2002. On that day, assistant coach and former player Mike McQueary came to Paterno’s residence shaken by something he witnessed in the football team’s shower room: He saw Sandusky with a young boy, both naked. McQueary isn’t taken to task in the film, for not immediately addressing the situation, and for instead telling Paterno. Paterno would contact athletic director Tim Curley, who brought in Gary Schultz, a school vice president who oversaw campus police, which none of the men called.

Levinson forces the viewer down a path with Paterno, using the coach lying in a cramped MRI machine as his examination tool to guide the film down into its layers. In the outcry leading up to and following the film’s release, a good number of observers believe the blame should be spread in different and deserving directions—from university officials including McQueary to officials at Second Mile charity, and child welfare employees.

However, first one has to understand Paterno’s reverence and power as a teacher, an iconic figure, and institutional leader. Pushing the strength of college football on America aside, in consideration of his influence on Penn State, Levinson shows a man betrayed by his conviction. In one scene, we see the exacting measure of Paterno’s heft and unchecked hubris. When the Penn State board of trustees squelches his weekly press conference, Paterno has an interesting response: “Without my permission?” It suggested the board had gone rogue, not that Paterno’s accountability and increasing liability should be in question. In Levinson’s view, Paterno fully understood his power within the Penn State structure, and he believed it an immovable force.

Throughout the bulk of the film, questions arise about precisely what he knew, and when, quartering significant doubt even within his relatives who dared not directly accuse the patriarch of his evident impropriety. Paterno begins to understand the repercussions of his ignorance in slow reveals, like the use of his magnifying glass over Sandusky’s retirement agreement or rewatching the 1999 Alamo Bowl, Sandusky’s last game as a Penn State coach.

The final scene provides illumination to a question asked of Paterno at various points throughout the film. The rumors about Sandusky, in fact, had gone back to at least 1976. When informed, Paterno did not act, and Sandusky would stay on as his assistant coach for the ensuing 22 seasons. Over and over, Paterno and significant members at Penn State appear to have chosen football over the immediate welfare of helpless kids.

Levinson and Pacino, fortunately, don’t attempt to delve directly into Paterno’s thoughts to the extent that pulls conclusions. It’s left to the viewer to make that determination. Recently, nearly 300 Penn State letterman bashed the film saying in a terse letter, “[the film] has been described by producer Barry Levinson as a work of fiction, which is likely the only truth in the entire project.”

But it’s evident that the once-venerated coach hadn’t given the proper attention to the sheer idea that his longtime assistant could be harming children, even when likely presented with the intel on multiple occasions. You’d have to be a former Penn State letterman to believe otherwise.

Still not sure what to watch on HBO? Here are the best movies on HBO, the best HBO documentaries, and what’s new on HBO Go this month.