After eight years living as one of the most scrutinized people on the planet, it’s still easy to view President Barack Obama as a larger-than-life figure. No matter how many March Madness brackets he fills out on TV, no matter how many late-night shows or podcasts he appears on, no matter how often we hear about him getting Game of Thrones screeners months in advance, it’s hard to view him as just a regular guy. Because he’s not and he’ll never be—not to most of us.

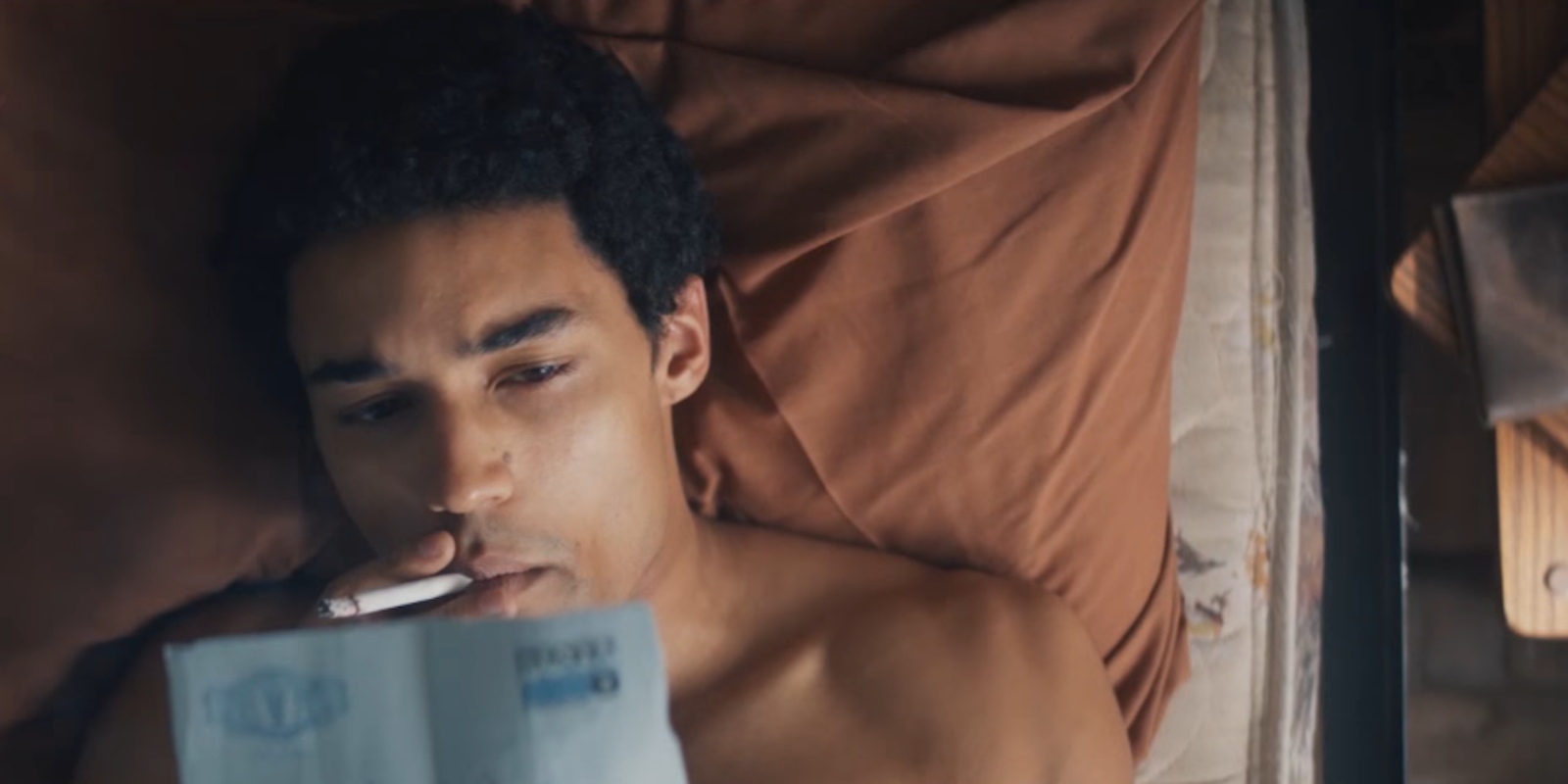

In the new Netflix film (now streaming), Barry, director Vikram Gandhi and writer Adam Mansbach go to great lengths to make the mythical something tangible. Eschewing the normal biopic blueprint of giving a broad overview that plays like a visual Wikipedia page, Barry tracks young Obama’s first few months in New York as a grad school student looking for his place in the world. We see him smoke often, usually by himself, and get numerous tracking shots of him walking the streets and just looking at all the different people. Barry’s Barry is just another face in the crowd.

Still, the film isn’t interested in capturing big moments that scream, “Get it? He’s going to be president one day!” Beyond scattered on-the-nose bits of dialogue, the story could just as easily be about a random guy named Barry without sacrificing much effectiveness. The movie refers to him almost exclusively as “Barry,” so it only feels right to do it here. It’s also a trick that helps view our president as a Regular Guy. It’s a humanizing, likely intentional directorial move.

But since we can only see the movie knowing Barry’s fate, it’s hard to watch without your own knowledge and assumptions clouding your judgment. Or, rather, that was something I struggled with and I think the movie played better for me because I was in a constant dialogue with myself to keep the movie separate from reality. The key to the movie’s success is the casting of Australian Devon Terrell, who makes a huge impression in his first major role.

Terrell’s performance goes beyond being a great mimicry to achieve a surprising level of verisimilitude. Whereas Jay Pharaoh’s impression on Saturday Night Live is freakish in its accuracy, you’re always aware that you’re watching an impression, but here Terrell creates an authentic character. His Barry is pensive and even keel, almost to a fault. This is on full display after Barry receives devastating news and spends a large stretch of the movie brooding. The movie goes to great lengths to put you in Barry’s head space, so when it’s time to cash in on that build up, it works.

On the campus of Columbia in 1981, Barry is a man out of place. He’s constantly being asked who he is, whether it’s the profiling campus security guard, sitting in class, or just meeting random people. It’s a question for which he usually answers evasively, and it’s the question that drives much of the film and leads to some of its strongest moments.

There’s an early scene where he’s playing in a pickup game on a park court, with “blacker” guys. Here Barry is quiet and lets his game do the talking for him. Compare that to the scene where he’s playing in a campus gym against all white guys. Here Barry is boisterous and playing more to the cocky athlete stereotype… until one of the guys from the park shows up and Barry goes back to his baseline. It’s like he’s trying on a different persona, and the awkwardness is instantly recognizable.

When Barry begins dating Charlotte (Anya Taylor-Joy), their mixed-race relationship not only mirrors Barry’s parents, but highlights Barry’s identity issues. It’s not that he doesn’t know who is, of course, but that he hasn’t learned to be comfortable in his own skin. Barry and Charlotte end up on a few dates where the “how Black is Barry?” subtext is so palpable that it may as well be a credited character.

By the end of the film, Barry has come to accept himself for who he is, at least to the degree that he can look relaxed again. For a movie this low-key and buttoned up, it plays like a major epiphany. Barry is like a distant cousin to Richard Linklater’s Before films, where the goal is come out feeling more connected to people you’ll never know, but who go through the same things as you.

These are movies where silences and thoughtful stares convey everything, and the conversations do bring you to the precipice of empathy, but allow you to get yourself the rest of the way there. And after eight years of watching President Obama, it’s nice to get an idea of who Barry is.