Today I washed my jeans. It’s the first time I’ve done so since I bought them in July, and yes, I’ve worn them every day.

It’s fair to say that I have an unhealthy relationship with my trousers—but I’m not alone. There’s an online community dedicated to freeing the world from the tyranny of washed denim. It was these people who I turned to last year when I embarked on a hunt for the perfect pair of jeans and subsequently found myself being sucked into the world of raw denim fandom.

So, what is raw denim and how does it differ from the pair of bootcuts rocked by the average Joe? During their construction, most modern jeans undergo a washing process after they have been dyed. There are multiple reasons for this: It takes off excess dye, it reduces future shrinkage, and it makes the denim softer. In essence, customers buying a pair of washed jeans will know how their jeans will look, feel and fit for the foreseeable future.

Raw denim is sometimes known as dry denim because the washing process has been skipped, leaving them stiff with starch and dark with dye. That’s why the first wash is so important. With pre-washed denim, the dye comes off uniformly during the first wash because the jeans haven’t been worn. But the longer you wait to wash a pair of raw denim jeans, the longer they can’t absorb the wear and creases of everyday life. When they are finally washed the dye will come off unevenly; more will come off the worn bits of denim, revealing “fades.”

This process has obvious aesthetic values that are impossible to replicate with pre-washed denim. No matter how hard designer labels try to get sandblasters to replicate the look of a worn pair of jeans, it will never look as natural as the fading causing by by months of hard wear.

Like all elite clubs, raw denim wearers are conscious of their superior status in the trouser-wearing world. They can’t help but wax lyrical about the mystical process that led to their privileged position of top-tier jeans wearer.

From Highsnobiety’s “Beginner’s Guide to Raw Denim:”

“Thus, when the time comes to wash a pair, careful measurements are taken to ensure that the fading to follow is a testament to the trials, triumphs, and tribulations of months past. To the staunchest raw denim enthusiasts, it’s akin to setting up a shrine and sacrificing months of passive devotion in order for each pair to be born anew. It is the caterpillar, with its alien body and slimy legs, becoming a butterfly with wing patterns unique unto itself…In short, raw denim is created as a ‘blank slate’ for each wearer to carve his or her own life onto.”

Washing

Every newbie raw denim enthusiast has the same question: When do I wash my jeans? The big fear is something called “fade failure”—wash your jeans too early and you might not break them in enough to yield strong fades, wait too long and ingrained dirt can start to break down the fabric which inevitably leads to the dreaded “crotch blowout.” And they might smell a bit too.

It’s a pressing issue and debate still swirls online. One person has gone 15 years without washing their prized Levis, while another conducted an experiment with a human biology professor that revealed normal levels of bacteria in his jeans after 15 months of wear. Apparently changing underwear regularly is key.

The consensus is that a six-month wait is generally required, though there may be anomalous circumstances.

History

Being raw is one thing, but if the quality of the denim isn’t up to scratch, it matters not. If you are a denim head there’s only one option: selvage. To understand why the word “selvage” is whispered reverently around forums, such as Reddit’s /r/malefashionadvice and Hypebeast, you need to learn the story of denim.

When denim started its rise from curiosity fabric to mainstream work-wear in late 1800s America, it was mostly raw and produced on slow shuttle looms with “selvage” edges. By the time Rebel Without a Cause was released in 1955, starring a denim-clad James Dean, denim had become emblematic of post-WWII youth culture. It was so popular that American Denim mills abandoned their shuttle looms for modern, faster machines.

But the old looms weren’t lost. Many were shipped to Japan as part of the effort to rebuild its economy. These specialist machines fell into the hands of family-owned textile companies, where they have been lovingly tended to over the decades. Their operators continue to produce small batches of high-quality denim.

This mix of vintage machinery and a culture of studied precision has found itself tailor-made for today’s youth who eagerly appropriate both vintage Americana and online Japanese culture. It’s a formula that’s served clothing entrepreneurs such as Supergroup very well.

Selvage

The selvage edges produced by these looms are simply the self-finished edges at the end of the fabric that keep it from unravelling. It’s created by passing a single piece of yarn horizontally between the fixed vertical pieces. The vertical pieces of yarn at each end are traditionally different colors. Many denim enthusiasts like to turn up the bottom of their jeans so that the selvage edge is on display—identifying themselves to other denim enthusiasts in the real world. It’s a bit like handkerchief code but for online clothing geeks.

Selvage edges are just that, edges. But to jeans aficionados, they mean so much more. Not only are these edges used as a structural component of jeans, the fabric itself is often very different from that produced on modern machines. Because selvage looms weave a much narrower roll of fabric, they are able to weave tighter and create a denser material. The textures these old looms are capable of producing can be quite startling to those used to silky soft new jeans.

Different Japanese mills are renowned for their different textures, some are rough, some are smooth, and some are “slubby.” Modern weaving technology has eliminated slubbiness from textiles, but for many fans it’s extremely desirable. The term refers to irregularities introduced to the yarn that yield an uneven and hairy texture in the finished product.

While the texture of selvage denim is important, the most pressing matter for denim-addicts is often the weight of the fabric, which is measured in ounces per yard. A heavier fabric lends itself to sharper contrasting fades, or so online rumor would have it. Most of these jeans come in at somewhere between 12 and a relatively hefty 16 ounces. But there are some rare jeans that come in much heavier, such as Naked & Famous’s 22-ounce Elephant 2 jeans that are frequently referenced in hushed tones on the forums.

For those inclined to geeking out and obsessing over details, speciality denim never disappoints. Rivets, pocket linings, belts and hem-length: There is no end to the finer points of denim-wear. But for true nerds there’s one thing that they need to seek out once they have purchased their jeans—a Union Special 43200G sewing machine. This machine produces a “chainstitch” that is the gold standard for hemming. (To save money most selvage jeans are sold with a standard long inside leg.)

This classic stitch is no longer used because it’s not very good and prone to unravelling.

It may be useless as a stitch, but it causes a fading pattern at the bottom of jeans known as “roping.” Roping is frequently touted as the best-looking fade by online enthusiasts.

Fades

While much of the raw denim craze might seem academic, the romanticized ideal of jeans becoming an individualized canvas does at least hold up in practice. This short video by Japanese video director Takayuki Akachi perfectly illustrates the raw denim dream.

For the uninitiated, the fading of jeans over time can look like a fairly unremarkable process. But the various patterns that form around different parts of the garment are distinct, with some individuals prizing certain types of fades over others.

The universally popular “honeycombs” are the creases that form behind the knee.

The more subtle “whiskers” are the streaks that form around the groin and pocket area.

“Stacks” are an acquired taste that can be induced by hemming the leg a little too long.

“Pocket prints” are love-it-or-hate-it fades caused by constantly carrying a phone or wallet in the same pocket.

Documenting fades is as natural to a raw denim lover as Instagramming a flat white is to a hipster. Raw jeans of every stripe have been photographed and posted online at every stage of their life: from new, to first wash, to undarnable demise. There’s even a movement to create a “Fade Compendium” that would bring all these pictures together.

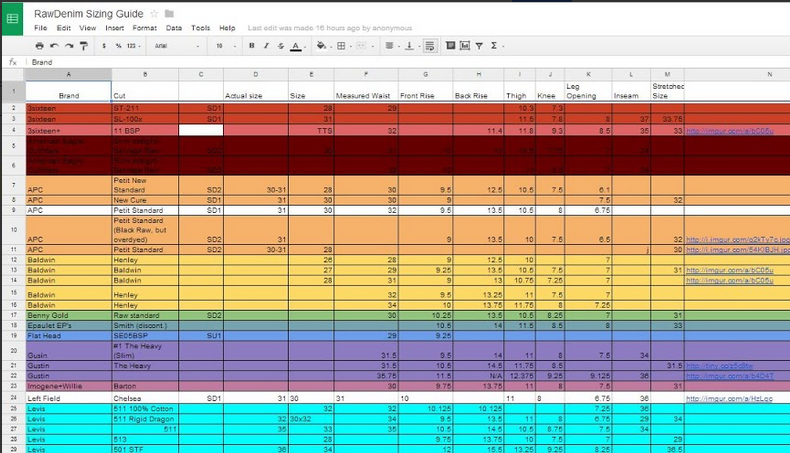

But where the online community has made a real impact is the dedication to making sure jeans fit. Jeans are notorious for their mismatching labels and actual sizing, but raw ones are even worse. Having not had the benefit of a pre-wash and with some not being sanforized, the final size of a pair of raw denim could be a bit of guess work.

The requests for help with fitting online are only matched by the eagerness with which expertise is offered. There’s even an open-source Google Doc spreadsheet that has collated sizing information for all the major brands.

Most people are perfectly happy to go on wearing their elasticated bootcuts. But for the few who aren’t, who wanted more from their pair of jeans, online denim fandom has opened up a hitherto inaccessible world. Lovingly handcrafted Japanese denim has been brought out of the shadows, hard to obtain jeans have been made accessible, and a generation of 20somethings have been seduced by the lure of limited production jeans.

Let’s hope my fades turn out good.

Photo by vikramdeep/Flickr (CC By 2.0)