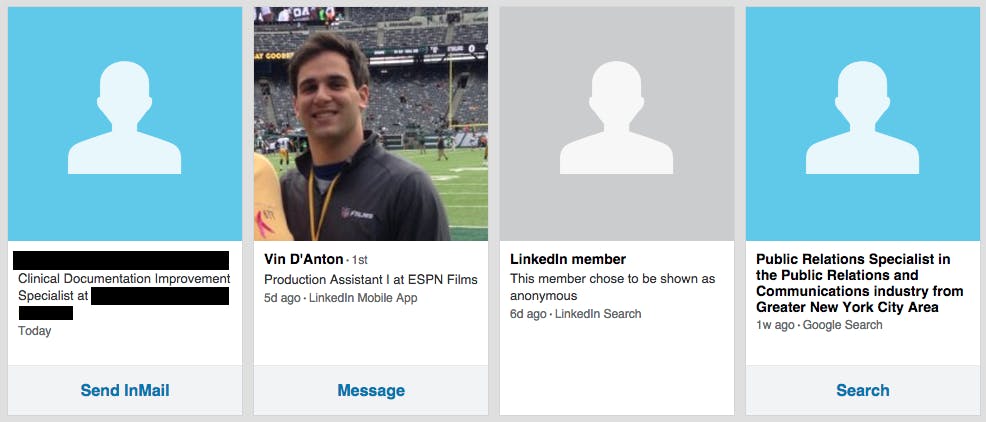

The other day, I accidentally ended up on LinkedIn. This sometimes happens when I click on the wrong tab in Chrome. Most of the time, I just close it and go to the page I meant to visit. But this time, I noticed the notification on the top of the page and went to clear it. “5 people viewed your profile,” it said.

Like anyone else, I was curious as to who had viewed my profile. So I clicked it. And then my heart stopped.

Three of the entries were fairly mundane. Two of them had chosen to hide their information, while the third was a college classmate who had recently shared one of my articles on Facebook.

But the most recent entry, the person who had viewed my profile on April 22, was the one that creeped me out. That person worked as a nurse at the hospital I was discharged from only a few days prior.

https://twitter.com/michejaw/status/590931196277850115

Other than an outpatient surgery in middle school and a brief stint in the ER for a broken arm in college, I’d managed to spend most of my life staying out of medical trouble. But a few weeks ago, I had some trouble breathing and was diagnosed with pneumonia. So I found myself spending a week-long unscheduled vacation in a tiny hospital room.

Now that I’ve been out for more than a few months, I’m much better. I’m back at my full-time job, and I even have enough energy to go visit my cat in the next room between writing articles (that is, when she’s not swatting me away). But the fact that a nurse had been curious enough about me to Google me and even visit my LinkedIn page was something I never could have anticipated.

https://twitter.com/HowellONeill/status/590931767340756992

Most people on the Internet are nosy sons of bitches. We try to find as much as we can about people’s social media lives, regardless of whether or not we’ll see them again (or even if we want to). I Googled my boyfriend before meeting him for the first time, and he later told me he’d read some of the articles I’d written as well. But I didn’t expect to be Googled by a medical professional who’d helped me recover from a serious illness.

But it did get me thinking. Although I was confined to a hospital bed for about a week, I had access to Wi-Fi through my laptop and cellphone. But even though I had access to the Internet, I had no idea how to tell people that I wasn’t OK. Even in an age of oversharing, where many people have no compunction about sharing every bit of their personal lives on the Internet, when it comes right down to it, there’s really no easy way to break that kind of news.

With this in mind, I came up with a list of rules for how to live on the Internet if you’re sick or in the hospital. Rule No. 1: Never add your nurse on LinkedIn.

1) Never tweet—unless you want to

When it became evident that I would be out for the count, I told the relevant people: family, my editors, my boyfriend, and the few friends with whom we’d be canceling our plans. But what about everyone else? How do you tell your Facebook friends and Twitter followers—those who care about your well-being, but might not be close enough to be on a text or phone call basis—that you’re sick?

For starters, you could just make a Facebook post about it. But you have to make a decision whether to make it public or private. It’s one thing to tell your family, friends, coworkers, and those people from high school and college you don’t really talk to anymore. It’s a different animal when you’re posting about your illness to hundreds (or thousands) of strangers who follow your tweets online.

Considering I subscribe to the “never tweet about your personal life” mantra, I never said anything publicly about my illness. After a few days, it looked like my window of opportunity had passed by. However, I made minor hints about my situation in vague tweets and mentions, so it was there if you cared to look. The closest I got to admitting I had been sick was posting a picture of flowers the folks at the Daily Dot sent me, as well as some sneaky self-promotion once I felt up to it.

https://twitter.com/michejaw/status/588441344235954176

2) Probably don’t take many selfies

I briefly debated whether to tell the Internet about being in the hospital by taking a selfie. (Pics or it didn’t happen, right?) But I quickly dismissed this idea for a few reasons. For starters, I didn’t want to be the subject of a snarky article making fun of people taking selfies from their sick beds. I also looked terrible, no matter how many practice selfies I could take beforehand.

We criticize and shame teens when they take selfies in inappropriate places. Although I wasn’t on my death bed or anything, I felt like announcing to the world that I was hospitalized may have been crossing a line. And considering how much we criticize how women look pretty much all the time, I didn’t think posting a photo of my puffy, bloated self would do anything for my self-esteem. But more than avoiding possible critiques on my looks, I wanted to avoid questions of what exactly I was doing in the hospital in the first place. I’d rather have that conversation face to face or via text.

3) Don’t post about someone else who’s sick unless they give you explicit permission to do so

For the most part, your Facebook friends are more likely to post when their own family members are in the hospital than when they’re in the hospital themselves. Usually, these posts are met with thoughts, prayers and sympathy from well-wishers.

But in most cases, it’s probably better to ask your friend or family member in the hospital if it’s OK if you’re posting about them. At the very least, you should figure out whether or not that person had publicly said something about their illness, because there are some pretty weighty consequences for venting about someone else’s illness without their permission.

A few days into my stay, I got some not-great news from one of my doctors. Something didn’t look right, and they’d have to do a procedure to get a closer look. If things looked grim, I’d need surgery.

Later, my sister posted a concerned Facebook status about the possibility that I would need surgery. I never saw that status, because she had purposefully blocked me from seeing it on her settings. And because I didn’t need the surgery, she put a panic in people that, in the end, was totally unnecessary.

Instead, I got a frantic text from my friend Anna, someone I’ve known for nearly 20 years (and hadn’t yet told about my illness) asking whether I’d need surgery. She only saw it because my sister had forgotten to change her privacy settings on Facebook to hide it from her. Posting something is one thing. Posting something and then trying to hide it is something else entirely.

She took it down after I asked—or at least, she said she did. But knowing that post was out there made a rough night at the hospital even worse.

4) Do some self-censoring

I have a twisted sense of humor. That was evident when I joked that my job—specifically, a recent Kernel issue I’d worked on—had inadvertently put me in the hospital.

However, when you’re in the midst of major health issues, not everyone might appreciate the humor, even if it’s clearly intended to be a joke. I learned that when an offhand comment I made on Twitter wasn’t taken too well by one of my editors.

@michejaw: :|

— Eric Geller (@ericgeller) April 12, 2015

There were some other strange moments as well. There was the oddity of watching the Orphan Black premiere screener while my IV pump beeped every 30 seconds or so. There was fighting HBO Go to watch Game of Thrones just like everyone else while on slightly less-reliable Wi-Fi. There was joking about my blood pressure while writing a breaking news story from my hospital bed around midnight. And there was the utter randomness of being paired with a roommate who happened to be a writer while in a hospital gown and pajama pants.

People were incredibly kind, both in and out of the hospital. But that gratitude was only expressed in private. Because I had never publicly said anything about being in the hospital in the first place, I felt like I couldn’t say anything about it on social media afterward. I didn’t get hit with questions from people, but not feeling like I could talk about it was somewhat isolating.

When do we reach the point of oversharing? We probably won’t ever reach a consensus on it, but as we share more of our lives online for everyone, not just those closest to us, can see, it’s easy to see there’s a stigma associated with sharing certain intimate, uncomfortable parts of our lives. That applies to being physically sick, but it also applies to other topics that make us uncomfortable, like depression, anxiety, or thoughts of suicide.

There’s a stigma associated with sharing certain intimate, uncomfortable parts of our lives.

Ultimately, it’s your call whether you want to broadcast something like this to your followers or keep it offline—and it should be yours alone. While we can make it easier to discuss things people don’t necessarily like to talk about, we shouldn’t feel pressured to do so. But if you’re someone, like a nurse, who takes care of patients on a regular basis, one thing’s for certain. If you’re going to creep on your patients after they’ve checked out, don’t do it on LinkedIn.

https://twitter.com/michejaw/status/588537301145288704

Photo via kristin klein/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)