Opinion

If I hadn’t seen his name, I’m not totally sure I would have recognized him—and even then, it wasn’t even the name he goes by, just his initials.

In the two decades that have passed since I last saw my rapist, his hair has thinned significantly. His face and frame are heavier, rounder. I brought my phone close to my face so that it practically touched my eyes, and then held it at arm’s length to get another perspective.

Yep, it was him alright. There he was, casually smiling, suggested by Facebook as a person I might “know.”

Like countless others, I am well-accustomed to mindlessly scrolling on social media feeds and coming across disconcerting posts. But it’s one thing to stumble upon a graphic meme, and another to be retraumatized by technology that puts a sexual violence survivor in contact with her attacker.

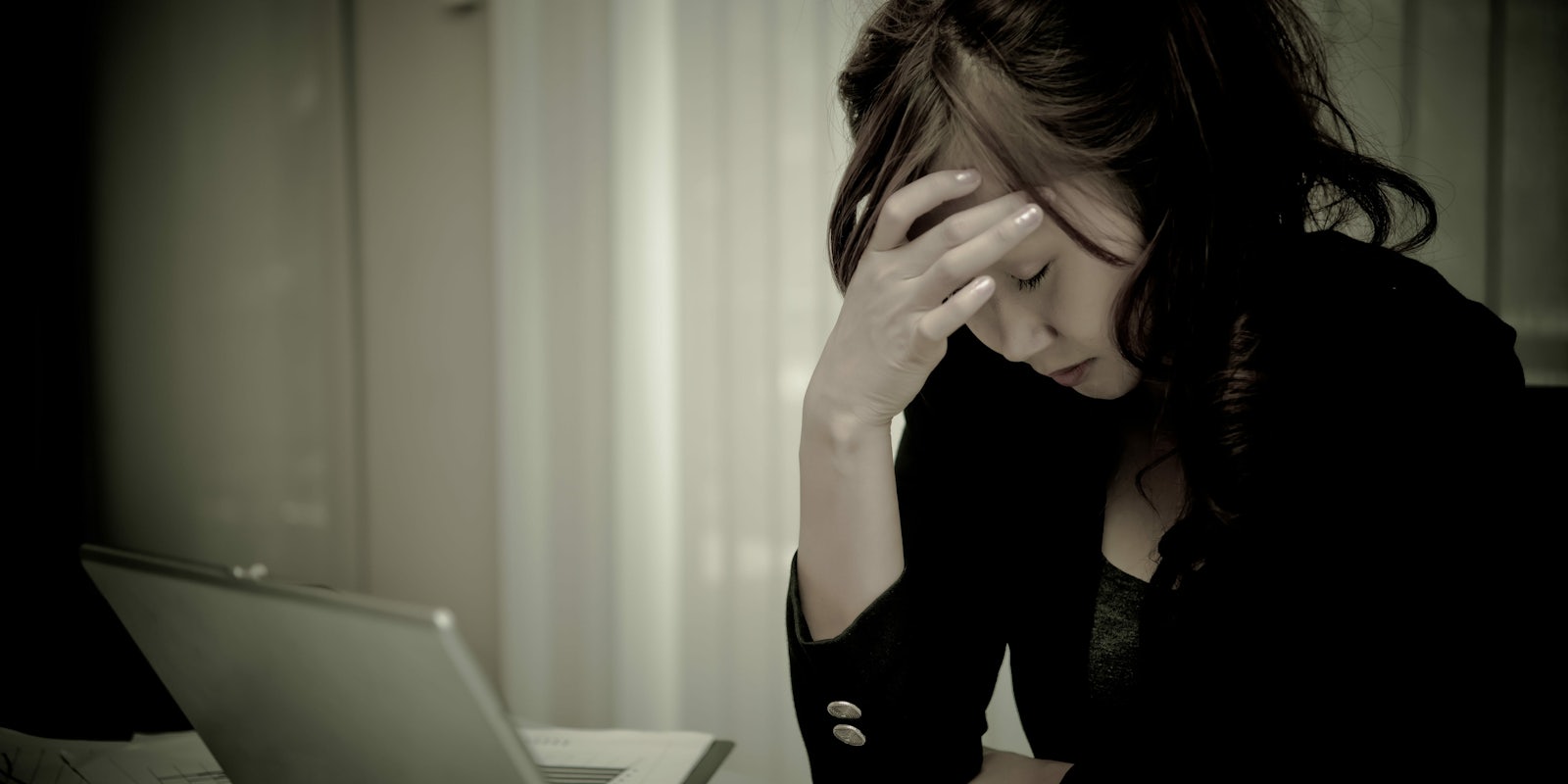

Seeing his face on a typical Tuesday morning flung me into the bottom of a depressive spiral that I didn’t fully ascend from until the following Sunday. A cold stream of sweat snaked its way from my armpit down my side. My mind felt fuzzy, like the batting inside a quilt. My stomach twisted and cramped violently, suddenly. I ran to the bathroom to have what I refer to as “terror poops,” which are precisely what they sound like; I’ve had terror poops regularly for the last two decades.

However, for most of those 20 years, I’ve grown comfortable knowing he’s nowhere near me. Before I moved away from the town we shared, every entry and exit from my house or car was terrifying until the doors locked behind me. I couldn’t even wash my face in the sink without having a panic attack because closing my eyes made me feel helpless and scared. I had to keep my eyes open. I had to be on the lookout for him.

And now, thanks to social media, no place felt safe.

. . .

The dangers of internet algorithms—the pieces of computer code responsible for your ever-personalized feed and who pops up in your “people you may know” box—are no joke. Sometimes they limit what shows up in your feed based on what you like, whether it’s fake news or well-sourced journalism; sometimes they subdue political action itself.

Facebook, in particular, has been criticized for its use of algorithms. Most recently, it has banned women who use the phrase “Men are trash” in their posts under the guise that it’s “hate speech” that violates its community standards. Others have also been vocal about the platform suggesting they friend their rapist—70 percent of survivors “know” the person who violated them so they likely have “friends” in common—and yet it doesn’t seem much has changed in the handful of years since the problem was brought to light.

When I reached out to Facebook to find out if the platform is working to combat situations such as mine, it took weeks to get a response. When it came, it was vague: “We take privacy seriously and of course want to make sure people have a safe and positive experience on Facebook,” a spokesperson wrote. “We’ve put safeguards in place to ensure people understand their privacy choices, moderate comments, block people, control location sharing, and report abusive content. For people who have experienced domestic violence, we work with NNEDV and others to inform how we think about building and providing resources on Facebook.”

In other words, its “friends suggestion” feature and its rapist-survivor-algorithm problem likely aren’t going away anytime soon. And if social media isn’t going to make things easier for survivors of sexual violence, then survivors must make things less painful for themselves—which is what we’ve always had to do. And the first step is understanding that our pain and anxieties are valid.

“For a person who’s been traumatized, there are many things that can trigger them—things like seeing pics from the past or seeing someone’s face or a comment can bring up all those feelings you thought you were over,” says Shaketa Robinson-Bruce, a therapist who works regularly with women who have been re-traumatized by social media. “And then you re-experience them and those feelings, things like intense anger, rage, sadness, overwhelming anxiety. It can then trigger feelings like self disappointment, shame, hopelessness, and powerlessness.”

She says with her clients, she helps them create a safer online presence. “We lock down their accounts to make them as private as possible, to where you can’t even get friend requests,” she says. “Then, for my clients as it relates to social media, I tell them to limit their time. Take a break. I encourage social media fasts.”

Experts agree that taking a break from social media is of paramount importance when it comes to trauma. “In a trauma incident, the first thing we do is take away the cell phone, the cable box. We have to control the flow of information so that people are not further traumatized,” says David Glick, a therapist who’s a member of the Department of Justice’s Trauma Team. “A good example of this is 9/11. The media kept showing images of the planes crashing, the towers falling. People couldn’t stop watching it. And the constant watching was making them relive that terror. Social media barrels through people’s boundaries.”

In the same vein, escaping and avoiding your abuser is often a top priority for those who’ve been sexually assaulted. Whether physical, mental, emotional, or all of the above, creating distance between oneself and the one who hurt them is one of the most basic forms of self-protection. Personally, I’ve made and fortified that distance in ways that are big (moving out of state) and small (avoiding the shade of pink I wore during an attack).

But as Glick says, the world we now live in is boundaryless. “With social media, information can get to primary and secondary victims faster than we can physically get on-site,” he says. “People will say things like they don’t understand why bullying is a big deal now. They got bullied when they were kids. But the difference is that we left it at school, and we went home, and we had that distance. We had a physical distance between the us and the trauma. But with social media, there is no distance. There is no boundary. Kids come home and there is no different or safe space because it’s all there in our phones, on our computers and devices that connect us. That’s the difference, and that difference is changing how we respond to these sorts of trauma.”

For me, a social media fast does look like the best answer. My therapist recommended getting outside and engaging the five senses. Unlike Facebook, at my favorite state park, no one controls what I see or experience but me. I can feel my feet crunch into the gravel pathway. I can see the effusive smile on my dog’s face and hear the nearby river gurgling as we walk along. I can pluck a few tiny, purple wildflowers that grow along the riverbank that remind me that today, I am safe. More importantly, those little violet blossoms do something for me social media rarely, if ever, does: affirm for me my own resilience.