Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, and Google will tighten their policies on dealing with hate speech in Europe after agreeing on Tuesday to a new code of conduct crafted by the European Commission.

The executive body of the European Union announced the code as part of an “effort to respond to the challenge of ensuring that online platforms do not offer opportunities for illegal online hate speech to spread virally.” The document was produced as part of the EU Internet Forum, an initiative launched in December 2015 to “protect the public from the spread of terrorist material and terrorist exploitation of communication channels.”

Among the actions expected of the tech giants, the companies will be expected to review—and act upon, if necessary—the “majority of valid notifications” of illegal hate speech in less than 24 hours, as well as promote counter-narratives to combat hateful content.

Introduction of the code of conduct come as fear of terrorist activity continues in Europe. Attacks on Paris and Brussels in the past year have put many in the region on high alert, and has given rise to a conversation about the role of speech—both in the form of encrypted conversations and content shared on social media.

France previously placed blame on Facebook and Twitter for failing to curb terrorist activity on the platforms, and there has been a growing tension between the companies and the countries in which they operate as pressure has grown to be more vigilant and aggressive in dealing with forms of radical speech; Germany previously convinced Facebook, Twitter, and Google to agree to a 24-hour removal rule for hate speech, and the sites have been working with the European Commission to address similar concerns.

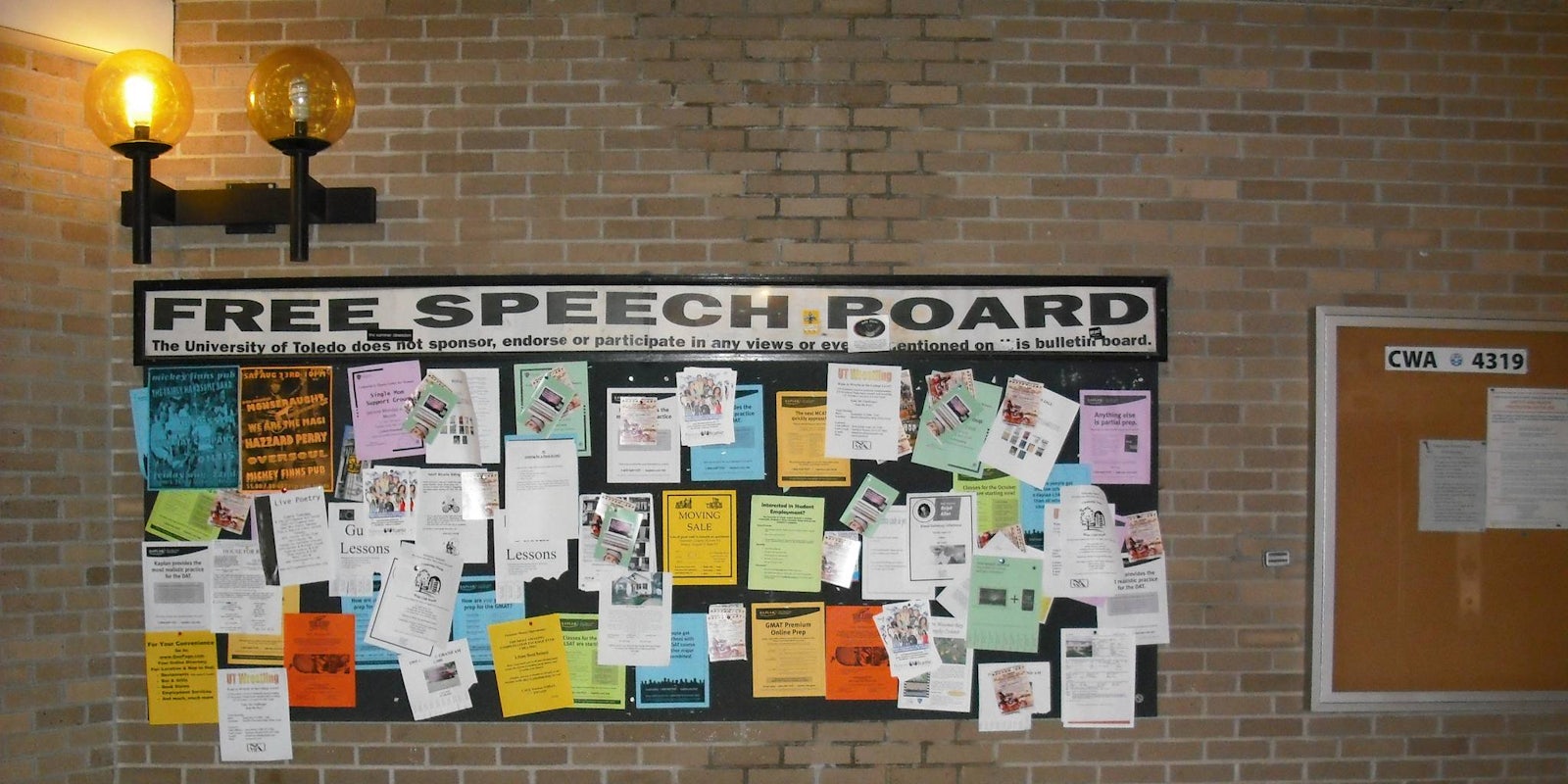

In a statement announcing the agreement, officials from the European Union and the tech companies involved all note the importance of ensuring free expression online while still taking action against illegal hate speech.

According to a study conducted by Pew Research in late 2015, nearly half of civilians polled in six countries in the European Union accept the government exerting control on speech against minorities. Germany was the most accepting of government regulation on speech, with seven out of ten in favor of it, while a plurality of those polled in the United Kingdom were opposed to the idea.

The United States is considerably more skeptical of any form of government-imposed restrictions, with just 28 percent of those surveyed comfortable with the idea. However, four in ten American millennials are open to censorship of hateful speech.

While there is little doubt about the importance of dealing with illegal forms of hate speech and terrorist activity, there is plenty of skepticism surrounding the code of conduct.

Danny O’Brien, International Director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation International Director, told the Daily Dot, “EFF is deeply disappointed in the crafting of this code of practice. With it, the EU companies have rubber stamped the widespread removal of allegedly illegal content, based only on flagging by third parties.”

O’Brien noted that the code “does not address that different speech is deemed illegal in different jurisdictions, nor how such ‘voluntary agreements’ between the private sector and state might be imitated or misused outside Europe.” He called it a “dangerous precedent,” and explained its potential harms could have been revealed with the inclusion of international human rights groups.

“Civil society was systematically excluded from negotiations over this ‘code of conduct,’” he said.

Ellery Roberts Biddle, Director of Advocacy for anti-censorship group Global Voices, told the Daily Dot what stood out the most to her was the lack of clarity on the role of “civil society organizations.” She was unclear who, if any, civil society organizations based in Europe were included in the conversation between the European Commission and social media companies.

The code calls for civil society organizations to play a role in flagging content that incites hate or violence, but provides little in way of detail. Biddle noted that the term “civil society organizations” can be applied to many different entities and may not exclusively refer to groups who prioritize and defend human rights and free speech.

She was unsure if organizations like Global Voices would be involved in that process, but said if they were then the European Commission is “essentially asking us to take on a responsibility and a certain amount of labor to help in this process.” She said many human rights organizations already provide this type of services, but not in any official capacity as is described in the European Commission’s code of conduct.

The lack of detail isn’t just a concern for CSOs, but for the those on the technical side of how companies are expected to handle removals. Biddle raised questions as to whether posts in Europe would be removed just in those borders or globally, and if hateful speech posted in countries that are less regulated but seen by users in the European Union could also be reported.

“There’s a lot of links in the chain here, and the way it was described wasn’t quite detailed enough for us to know exactly what it means in terms of how it might change or restrict the type of content that people see online,” she said.

Biddle also explained that she believed while there has been an increase in hate speech in the European Union, it still pales in comparison to elsewhere. “Content related to violent extremist groups…is very present in all of the platforms involved here in other parts of the world,” she said. Other nations, where the issue may be more prevalent, have less influence than the European Union in trying to push private companies to action.

Global Voices and EFF were not the only organizations that made public their concerns about the code of conduct. Advocacy groups European Digital Rights (EDRi) and Access Now also issued a joint statement that they would withdraw from future discussions hosted by the European Union Internet Forum for its “lack of transparency and public input” in the content of the code of conduct.

The Daily Dot reached out to Facebook, Twitter, and Google for response to criticisms levied by free speech advocates. None of the companies responded at the time of publication.

H/T The Verge