Opinion

Here’s a fun challenge: Head to your local bookstore and check out the gender, sexuality, and “sexual wellness” section. Count how many books are for sale about trans sex. If you’re lucky, you’ll find one: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves. If you’re particularly blessed, there may be the trans erotica collection Nerve Endings or the sex ed book Girl Sex 101.

But in most cases—especially for those of you living outside of major cities with a prominent trans community—you’ll find nothing. Save for a few books on gender transitioning and what it means to be transgender, there’s very little out there for trans people that want to figure out how to masturbate, orgasm, or have pleasurable sex. But don’t worry, if your parents need to know what “coming out” means, there’s plenty of writing out there for them.

Trans people don’t have enough resources for their lives beyond gender transitioning. It’s why I started my column Trans/Sex; I wanted to bring the discussions about sex and bodies found in Brooklyn house parties and Toronto queer haunts to people who barely know any trans people in real life. But I can’t do that alone, nor should I. Visibility is about more than one person.

The Trans Day of Visibility’s website says today is an annual holiday “dedicated to celebrating the accomplishments and victories of transgender and gender non-conforming people” while also “raising awareness of the work that is still needed to save trans lives.” TDOV sits in dialogue with the Transgender Day of Remembrance; while the latter mourns trans losses, TDOV honors trans people in the world and what makes us truly unique.

Visibility is complicated, because every trans person has a different approach. Should trans folks be celebrating their transness out loud? Should we be raising trans voices that are often missing in mainstream conversations, like trans sex workers and incarcerated trans people? Should we be celebrating our trans ancestors who risked their bodies and lives for where we are today? Or is it a mixture of all three? I’m inclined to think it’s all of the above. Yet we’re consistently forced to make concessions about our gender identities for acceptance from cis people.

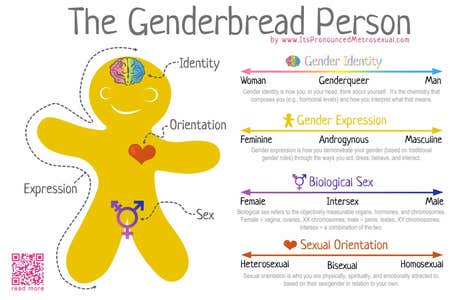

The original “Genderbread Person” is a really good example. The chart, which has seen multiple renditions over the years, was developed as a simple way to explain how gender, gender expression, sex, and sexual orientation are not mutually exclusive to one another. To a certain extent, it works. But I don’t think the Genderbread Person is particularly radical.

For one, the Genderbread Person and its various offshoots (such as the Gender Unicorn) tend to place sex in a binary: one is either assigned male at birth, assigned female, or sits somewhere in between the two. However, the actual lived experience of being trans and having a “sex” is much more complicated. What makes a person’s sex female? What makes it male? Is a trans woman’s sex still “male” if she’s on HRT? Is her sex “male” if she’s not on HRT?

The Genderbread Person doesn’t break down how these words are inherently gendered in a way that just doesn’t make room for various bodies. Unsurprisingly, that’s because the Genderbread Person tries to make room for trans acceptance by anchoring itself to cisgender conceptions of gender. Hell, the original Genderbread Person defined sex based on “the objectively measurable organs, hormones, and chromosomes” a person has. Its logical conclusion implies a trans woman has a male sex.

Granted, the Genderbread Person has changed over the years—the latest version describes “anatomical sex” based on “sex characteristics” and “the sex you are assigned at birth.” But phrases like “sex assigned at birth” are no better. Sure, it’s convenient to say I was “assigned male at birth” so cis people understand I have a penis. But is it really fair to me to describe my sex based on what a cis person assigned me when I was born? If I say, “I’m an AMAB trans woman,” I’m literally saying “I am a woman that was told I had a male body.” I don’t want to define myself based on a sex I never asked to be assigned; I just think I’m a woman with a penis, not much else. So I’d much rather have another set of gender-neutral words separate from that entire framework, something like “I am a woman with a phallic sex,” “I am a man with a vaginal sex,” or “I am a nonbinary person who is intersex.”

For me, that’s what trans visibility is: letting me be seen and heard the way I want to be seen and heard. It centers my voice, not a cis person’s voice.

There are other issues with trans visibility in the mainstream. The media is oversaturated with stories that hyperfixate on gender transitioning, as opposed to the life experiences trans people have after transitioning. There’s practically no room made for nuanced trans protagonists in big-budget films, TV, and literature, and barely any room for them in even the most niche spaces, like speculative fiction at major publishing houses. Where are the stories about trans women space captains, trans men in a cyberpunk dystopia, or trans nonbinary folks who slay dragons and hang out at the local inn? While trans and queer creators are writing these stories every day, they rarely get the proper attention they deserve.

That’s because modern trans visibility wants to depict us in a purely normative way. We go to school, we watch TV, we do taxes, we go on a date, and then we go to bed. In between, we talk constantly about our gender transitionings. This in and of itself isn’t a problem, but it’s so incredibly rare to ever see trans people look any other way. Our lives are a spectrum of experiences, and there isn’t just one way trans people go about their days.

Some trans folks live in communes, punk houses, queer apartments, or surf from couch to couch. Others struggle with poverty, homelessness, and either live in shelters or don’t have anywhere to go but out on the streets. Our politics usually (albeit, not always) lean left, even veering toward socialism, communism, anarchy, and anti-fascism. Some of us do sex work or work in adjacent spaces, like adult content creation. Open relationships, orgies, sex parties, kink, and polyamory saturate our sex lives. Many of us are Extremely Online, too, because the internet lets us connect with other trans people. And yeah, some of us are normies who work and make dinner with our partners and live private lives.

But if you’re cis, you probably didn’t realize all of this. That’s on purpose. In order to reach mainstream acceptance, we tend to water down our stories and twist them until they’re no longer transgressive. A perfect example is Andrea Long Chu’s controversial tweets where she implies trans women secretly want to be cis women. It’s not that she’s entirely wrong—many trans women aspire to be seen as cis women to the point where they internalize transphobia. But the way she executes that explanation is so simplistic and so generalized that it’s ridiculous. To argue all trans women see cis women as “patently superior” is to suggest all trans women aren’t proud of being trans. Many of us are perfectly fine with the womanhood we have, both metaphorically and literally. But we’re told that transness is wrong, bad, and inferior to cisness, to the point where being proud to be a trans woman with a penis is seen as bad, wrong, or worst of all, masculine.

Visibility isn’t real if it comes at another trans person’s expense. No, genuine, authentic trans visibility is honest. It’s radical. It doesn’t care what cis people think. It cares what trans people think. If we want to be visible, we must create trans stories for other trans people. We must put ourselves first, always. Otherwise, we’ll never give young, newly transitioning trans people the resources they need to see themselves in the mirror.