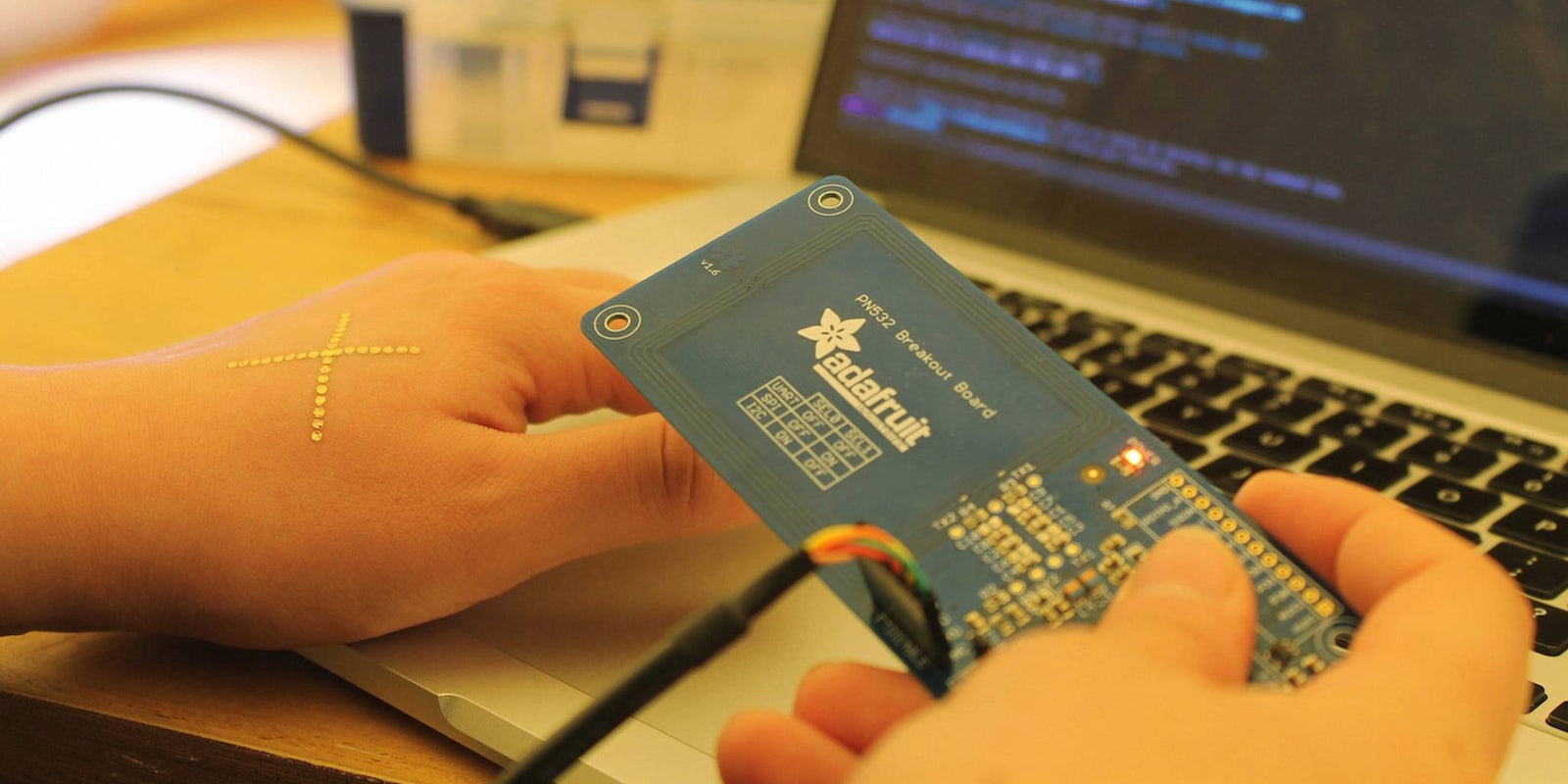

Katy Moe is a cyborg. A glass-coated NFC transponder is implanted in the flesh of her left hand between her thumb and index finger, with a unique identifier and the capability of storing up to 888 bytes of data.

The NFC chip can transmit data up to four centimeters away from her hand, and is programmed to share anything your average NFC-enabled device can share. For instance, she can program it to share a link to her website, pay for something, or even an auto-play a Rick Astley video. At Twilio’s developer conference on Tuesday, Moe, a programmer at UK-based Improbable, took the stage in a live coding demo to show people just how easy it is to program the technical bits of her body using JavaScript.

Moe describes cyborgs as anyone who has augmented their bodies with non-human hardware; by that common definition, people with pacemakers, metal kneecaps, or cochlear implants would be considered cyborgs. Beyond simply augmenting bodies with non-biological systems, bio hackers and human cyborgs also experience what Moe calls “embodied data,” the idea that a piece of hardware encoded with data is statically stored inside her body and lets her truly embody knowledge or information in a tangible way.

“I wanted to expand capabilities of my body. I was really intrigued by the idea of people who put magnets in their body, and the idea of getting an extra sense,” Moe said in an interview. “I have the ability to store data and communicate with various machines with a part of my body, which is a capability I didn’t have before.”

She implanted the device into her hand almost one year ago, with a syringe that came enclosed in a sterilized package to prevent infection. She went to a piercer who had implanted things into people before and, similar to a body piecing, he injected the 12 mm by 2 mm device into her hand. Because it was done without a medical practitioner, she didn’t use any anesthetic for the procedure. A temporary tattoo marks the invisible spot beneath her skin where the implant resides.

“I have the ability to store data and communicate with various machines with a part of my body, which is a capability I didn’t have before.”

The person who implanted the NFC chip was not a doctor, and as Moe explained, the relationship between bio hackers and the medical community is virtually non-existent, especially in the UK where publicly-funded healthcare doesn’t cover procedures like technological implants.

For Neil Harbisson, a body hacker with a camera implanted in his head that lets him translate colors into sound, finding a doctor to perform the surgery was difficult. A European medical ethics committee didn’t sign off on the operation, so he found a surgeon to do it anonymously.

“I don’t know how many people have gone to their doctor and told them about this, but I don’t think they’d really understand very well,” she said. “I don’t think I will tell my doctor about it because they’ll probably think it’s a foreign body that needs to be removed, or that I’ve got some sort of problem.”

There is a robust and growing community of bio hackers, sometimes called “grinders.” People implant NFC chips, magnets, and even vibrating devices into pelvic bones to augment the human experience. Among the most complicated and graphic body modification includes transdermal LED light implants under the skin that glow, mimicking bioluminescence.

Surgically implanting devices into your body is not a new idea, though as devices shrink and their usefulness grows it’s gradually becoming more prevalent. In 1998, Kevin Warwick, widely regarded as the “the world’s first cyborg,” put an RFID tag into his arm, enabling the professor to open doors as he walked around the University of Reading.

Moe’s implant is relatively simple and small compared to, say, a fitness tracker.

The tiny implant is the same tech that identifies devices paying with Apple or Google payment systems on our mobile phones, or the cards we swipe to get on subways or buses. Theoretically, Moe’s NFC chip could be used to tag transit systems in London. Moe wants to create a safety deposit system that remains locked until her unique identifier tells it to open, ensuring the safety of valuables when she’s not physically anywhere near the box.

A physical implant identifying individuals through unique IDs is a bit dystopian at first blush. Privacy red flags appeared in my mind as she described how the connected implant ties her to a number that could potentially be programmed to do something she doesn’t want, or allow people to brick her information simply by putting their phone near her hand. But she’s not concerned with the privacy aspect, and views the implant as a way of asserting authority and ownership of her body, the same way people get piercings or tattoos.

“It’s comparable to a fingerprint. It’s as uniquely identifying, and as easy to take; someone could find my fingerprints on something,” she said. “I do wonder whether I’ve stepped over a threshold into plugging myself into the Internet, but it’s not network-connected unless there’s an electric field around it. The idea that there’s a unique ID and in theory you can track me with it, that a conversation we need to have.”

When talking with Moe, I realized her NFC chip is similar to Facebook or Google, or any of the digital services that track is across the web. Web browsers and sites identify where we go, what we search, who we talk to, and almost any personal data you voluntarily give over to access apps that is, in turn, used to target us with advertising.

What makes us wonder is the biological factor; tech making that final leap from our fingertips to the skin beneath them.

In fact, Moe doesn’t have a Facebook account because of that very reason. She feels like it’s an invasion of privacy.

“I feel more in control of this because it’s physical. I feel it’s more in my control of where my hand goes. I don’t believe it’s in anyone’s interest, let alone commercial interest, to track me through my NFC chip,” she said. “And if someone really wanted, they could go and spoof a load of IDs in the system. With a Facebook account it’s a bit more difficult.”

Reactions to her implant are generally positive, and people are curious to test out the NFC capabilities. She said her father thought it was great, while her mother was much more skeptical. If and when she decides to remove it, it will be a more intense procedure than implanting it, requiring a scalpel to slice through layers of skin and tissue to remove the tiny device.

By physically connecting to bits of technology, Moe said it raises questions regarding our relationship to the digital world and forces us to rethink and potentially redefine what technology is and how we use it.

“You have to confront your relationship with technology when you implant something with yourself, but before that you’ve probably been on the computer most of the day, been on your phone the rest of the day, conducted most of your relationships through the internet,” she said. “You’re already interlaced with technology in less-physical and immediate ways.”

You are probably one small incision away from being a cyborg yourself, with your phone always in your pocket or hand, reading this through a screen you’re glued to on a regular basis, and potentially even finding this story through a social network you spend hours of your week browsing.

It’s biology that makes us human; the augmentation and addition of the tech we use every day makes us cyborgs. But is it really that different than our behaviors that define who we are anyway? The ultimate question is what comes next, after technology makes the leap from our fingertips to the skin beneath them.