After 22-year-old Elliot Rodger, prompted by his viciously cruel beliefs about women and sex, murdered six people and injured seven more this past weekend, many men on the internet bravely took up the banner of manhood and reminded the women speaking out about sexism that “not all men” are violent and murder people because women wouldn’t have sex with them.

In response, a hashtag called “#YesAllWomen” was created to address the idea that, yes, not all men are violent and misogynistic, but yes, all women are impacted by male violence and misogyny. The thousands of tweets on the hashtag address how women are impacted by sexism every day, not just when tragedies like this mass shooting occur.

The hashtag went viral over the weekend and has already been covered by the New Yorker, Time, The Atlantic, Washington Post, CNN, and other mainstream outlets, as well as more tech-oriented blogs like Techcrunch and Mashable. These journalists included many examples of #YesAllWomen tweets in their stories, thus given them even more exposure. Even well-known figures like Nancy Pelosi, Lena Dunham, Neil Gaiman, and Joyce Carol Oates have tweeted using the hashtag.

The hashtag is about Rodger in a way, but it’s really about much more than that. Women are using the hashtag to show how sexism pervades their lives and how Rodger’s violence was just an extreme extension of ideas and behaviors that we commonly encounter from men.

As the New Yorker‘s Sasha Weiss writes, “Elliot Rodger earned the fame and infamy he wished for through his act of violence, and now everyone can read about his grotesque ideas. #YesAllWomen offers a counter-testimony, demonstrating that Rodger’s hate of women grew out of attitudes that are all around us. Perhaps more subtly, it suggests that he was influenced by a predominant cultural ethos that rewards sexual aggression, power, and wealth, and that reinforces traditional alpha masculinity and submissive femininity.”

Of course, women have been speaking about these daily experiences with sexism since long before Twitter and hashtags existed. Second-wave feminists in the 1970s and ‘80s analyzed everyday interactions between men and women to point out the power differentials that these interactions revealed. Of course, this is part of what gave them their unfair reputation as “man haters.” They astutely noticed that most men get away with ignoring, talking over, and dismissing women because that’s how they’d learned to behave.

Even on Twitter, discussions of sexism are commonplace. The Everyday Sexism account collects tweets from women about the constant acts of marginalization and oppression they experience like background noise. The project inspired a book by Laura Bates, and, predictably, a review in The Telegraph that claimed that the project and the book are “unfair to men.”

But it seems to have taken a mass murder for this conversation to really take off, which is dismaying to those who hope to persuade people that “misogyny” isn’t just brutally slaughtering women for not having sex with you (though this, too, happens more often than many would like to think). It’s also telling women to prevent their own sexual assault by not dressing “like sluts.” It’s also blaming women for “friend zoning” men by not being sexually interested in them. It’s also dismissing the gendered threats and harassment that women receive online because it’s “just theIinternet” or “just trolling.”

Some viewed the #YesAllWomen hashtag as an inappropriate “politicization” of a tragedy. This charge gets thrown out whenever people discuss the political ramifications of a tragic event within a time frame that’s subjectively deemed “too soon,” whether the actual subject is gender roles, gun control, police incompetence, or other relevant issues. (Mental healthcare, incidentally, is generally exempted from the “politicization” accusation—because many people are very, very vested in the idea of blaming violence on mental illness.)

In general, “Stop politicizing this tragedy” seems to mean, “I don’t like your conclusions about the causes of this tragedy.” Rodger made his motivations very clear before he carried out the shooting, and those motivations are political. Pretending they weren’t does nothing to respect the victims, nor to prevent future misogynistic violence. The women using #YesAllWomen to respond to the shooting are correctly pointing out its causes and the ways in which such horrific violence can grow out of more casual, everyday, seemingly harmless expressions of sexism.

My hope is that the conversation continued and promoted by #YesAllWomen—it was not started by it—continues past this news cycle. Viewing this tragedy in isolation from the cultural and systemic factors that allowed it to happen may feel more reassuring, but it will not help prevent violence or sexism in general. The fact that it took such a violent and high-profile crime to get this conversation the attention it currently has says a lot about the invisibility of sexism and the determination of most people, even many women, to avoid thinking about it.

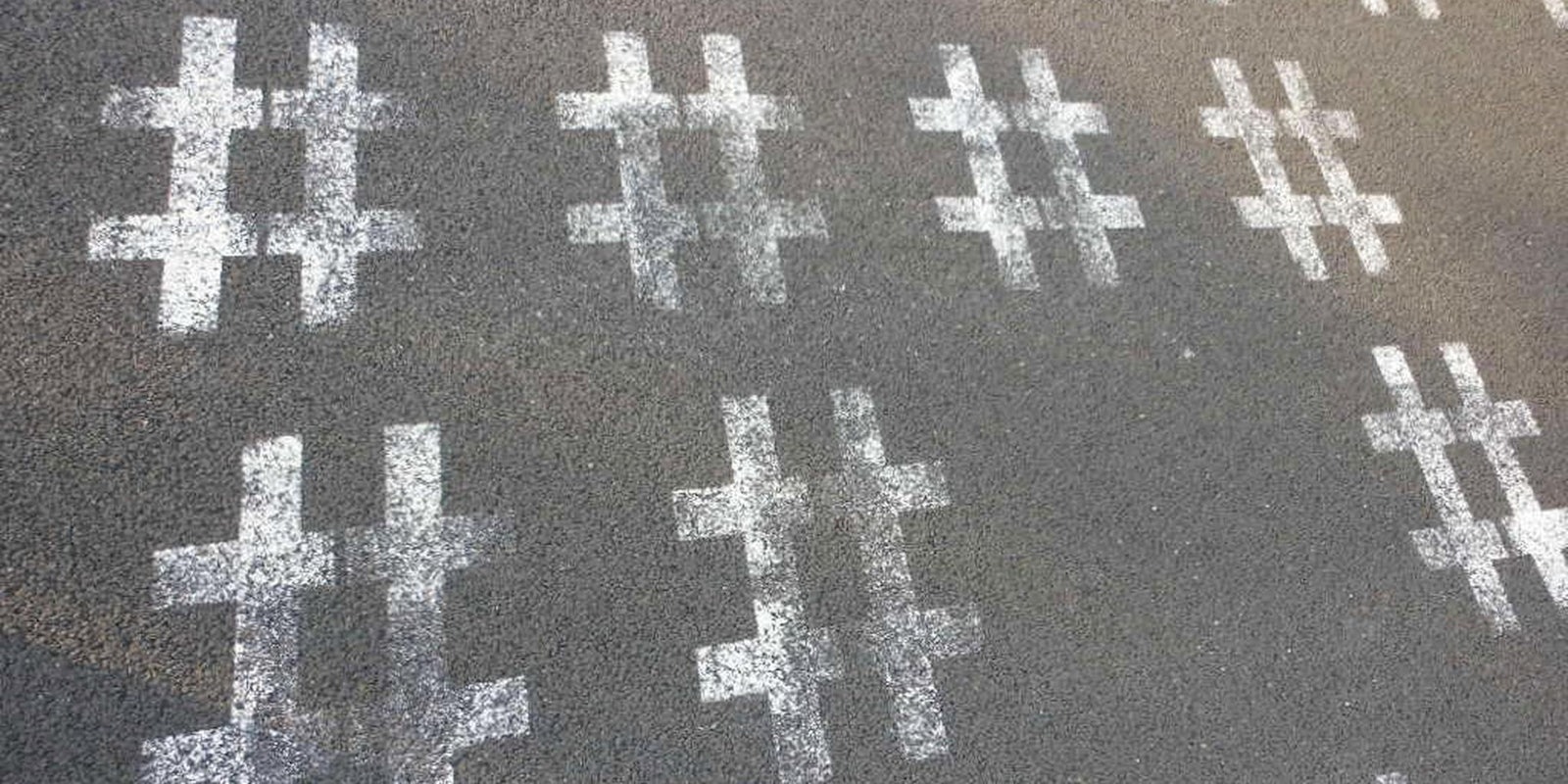

Photo via mikecogh/Flickr (CC BY S.A.-2.0)