The “grinning face with smiling eyes” emoji has gotten me into some confusing messaging threads. Usually they go a little something like this:

“😁”

“Oof, sounds rough.”

“Wait, what? That’s a smile…”

“No, it’s a grimace.”

The person on the other end of the message is usually using an Android device, so to them, the emoji does look like a big smile. For me, an iPhone user, it looks like a sarcastic smile or unhappy face.

Then there are new emoji that don’t exist on all platforms, where they might show up as a blank square or question mark, and yet still have varying degrees of interpretation on those devices which can render them.

Teaching mom about emoji pic.twitter.com/EGgFvEtC4b

— Selena (@selenalarson) March 8, 2016

I’m not the only one who has misconstrued emoji in conversation, or read them in a different way than the sender intended. A new study shows that people can misinterpret the emotion and meaning in emoji quite significantly, even when they’re on the same platform.

There’s no standard emoji font, and while the Unicode Consortium tries to have some cohesion across platforms, there are still significant variations between emoji on mobile and the web. The tiny cartoon renderings of people, places, and things look different when you’re on an iOS, Android, or Windows device, on an OS like Firefox, or web service like Twitter.

Despite reminding us of hieroglyphics, emoji are not a language unto themselves, rather a language supplement, but like text language, emoji interpretation can change depending on the icon you see on your device.

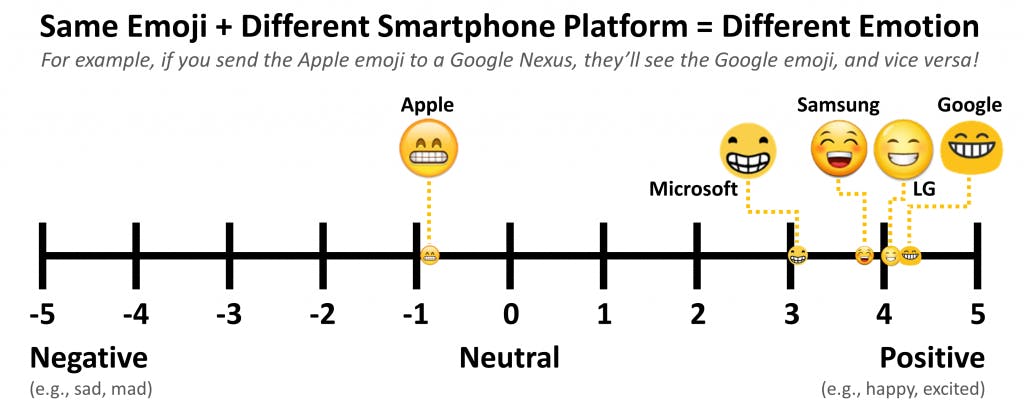

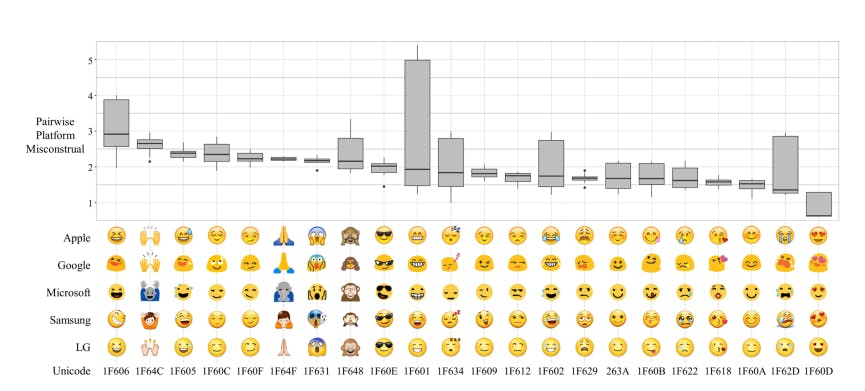

Thanks to the variety of platform standardization, emoji you send may look different to the intended recipient. To find out how the variations impact the way people interpret emoji and conversation, researchers at the University of Minnesota’s GroupLens research lab conducted a survey using 22 human-like emoji across Apple, Google, Microsoft, Samsung, and LG platforms. Researchers asked 334 participants five questions, including what they considered the sentiment to be (positive or negative on a scale of -5 to 5), and when they would use the emoji in conversation.

The research was published in the paper “Blissfully happy” or “ready to fight”: Varying Interpretations of Emoji.

Researchers found that 40 percent of emoji tested had a “sentiment misconstrual score” of 2 or more, so when two people look at the same emoji, the sentiment disagreement between them would be greater than or equal to 2. And even people within the same platform wouldn’t agree on the whether the emoji leaned positive or negative—Apple’s in-platform sentiment misconstrual was 1.96, while Google’s was 1.79.

“You can think of this as being a translation problem,” researcher Loren Terveen said in an interview with the Daily Dot. “I might say a sentence in one language and it gets translated to another, and nuance may be lost and people may be confused. The same thing is true here. I see one emoji rendering, you on your phone may see a different rendering. I don’t know it, and I don’t know exactly what you see.”

The grinning emoji had a wide range of sentiment misinterpretation across platforms, and researchers found many other differences in the way people described emoji, both in words and feelings of positivity or negativity. The heart-eyes emoji, an obvious one for most of us, was frequently associated with “love.” Other more ambiguous emoji differed.

The emoji rendering with the largest within-platform semantic misconstrual (0.97) was Apple’s rendering 😒 of “unamused face.” The responses for this rendering show several different interpretations—“disappointment,” “depressing,” “unimpressed” and “suspicious.”…

The top words used to describe the Apple rendering 🙌 are “hand, celebrate,” “stop, clap” for the Google rendering, “praise, hand” for the LG rendering, “exciting, high” for the Microsoft rendering, and “exciting, happy” for the Samsung rendering.

Linguist researcher Gretchen McCulloch says that emoji can be considered a digital equivalent tone of voice, facial expression, and hand gestures—the nuances that accompany our IRL conversations. But these online nuances are dictated by a group of individuals making rules on how and what we use to communicate.

“One of the problems with emoji as a form of communication is that they’re created by big companies and the Unicode Consortium who aren’t necessarily particularly good at being emotional arbiters for the entire world,” McCulloch said in an email. “With my own face and hands, I can make them do whatever I want, it’s very grassroots, but with emoji I can only send what the emoji designers have decided I should be able to send.

“Sometimes this is cool—I can’t make my literal eyes into hearts, but I can send a heart-eyes emoji. Sometimes this is confusing—I think this study is providing solid numbers for a feeling that people with friends on different platforms have known for a long time. I’d really like to get all the designers from all these different platforms in a room together and make them hash out a single emoji standard. Or maybe get the Unicode Consortium to give more specific graphic design guidelines.”

Emoji have become popular ways to communicate via pictorial representations of thoughts and feelings, but it’s not the only form of online communication that’s often misinterpreted.

A 2006 study shows flaws in digital communication regarding sarcasm and humor. Thirty pairs of students sent 20 emails in a sarcastic or serious tone. While senders mostly expected the recipients to correctly interpret the tone of the email, recipients got it right just over 50 percent of the time.

The cause of the email misinterpretation, researchers wrote, has to do with our egos. Egocentrism is the idea that people can’t detach from their own perspectives, and ascribe their perspectives and beliefs to communications without understanding how other people will interpret them.

The emoji research didn’t study this affect of our ego misinterpreting smiling faces, but researchers do note the ways communication can be internalized.

One main way is through joint personal experiences, which fall into joint perceptual experiences—perception of natural signs of things—and joint actions—interpretation of intentional signals. Emoji usage falls into both: in addition to intending to communicate meaning, they also require perceptual interpretation to derive meaning.

Hannah Miller, the paper’s coauthor, said researchers barely scratched the surface on the potential for emoji research. She wants to expand the study to include cross-cultural emoji use and how emoji meanings can vary in different geographic and demographic areas.

“Another angle that we think is interesting is that emoji can be interpreted differently depending on the culture that you’re in,” Miller said. “Emoji originated in Japan, and some of them have transferred over, and we’ve heard stories of emoji meaning different things here than they do in Japan. And I’m sure there are other cultures that have different interpretations.”

Dr. Brent Hecht, computer science and engineering professor at the University of Minnesota and advisor on the emoji research, said that it’s not just human interaction this research could potentially impact. The ambiguity of emoji also raises an interesting question as to how computers can learn to communicate: If people don’t have a concise understanding of what emoji mean, how can we train artificial intelligence to recognize and use emoji in conversation?

The emoji study could lead to further research regarding how the tiny icons change our perception of conversations, including analyzing interpretation of sarcastic or humorous emoji use, or figuring out how much knowing someone and having an established conversation style impacts understanding.

To that end, the research could help us lonely hearts understand why those strangers we chat with on dating apps just don’t seem to interpret our messages in the ways we intended. Miller joked that perhaps emoji could be a barometer of budding relationships.

“If people don’t have [any] relationship to go off of, and they don’t know if they’re seeing the same emoji or not, then it could help if they are on the same page and interpreting it the same way, but it could hinder if they have different interpretations,” Miller said. “So maybe the emoji can actually figure our how compatible they are.”

If you are concerned that your emotional nuances aren’t being interpreted correctly, McCulloch says that avoiding ambiguous emoji can take the confusion out of communication.

“Personally, I just don’t use some of the emoji that I know are very different across different platforms, like the grinning face with smiling eyes–there are other smiling emoji that are less ambiguous,” McCulloch said. “So if people want to make sure they’re understood across platforms, this study has conveniently given us a list of the most and least ambiguous emoji to pick from.”