As the Internet mourns the loss of Cecil the Lion, the very existence of much of the Earth’s wildlife hangs in the balance.

At 13 years old, Cecil lived freely in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park until he was killed by Minnesota dentist Walter J. Palmer in early July. With the help of two local poachers and $55,000, Palmer lured Cecil out of the park using an animal carcass as bait and shot him with a crossbow. They trailed the wounded Cecil for 40 hours before ultimately shooting, killing, beheading, and skinning the lion.

The Telegraph identified Palmer as Cecil’s killer on Tuesday, prompting intense outrage from people across the Internet, who in turn left vitriolic reviews on Yelp and Facebook; they even left angry messages on the door of his office. Twitter users also doxed Palmer, who began receiving death threats. An online petition demanding “Justice for Cecil” has collected over 800,000 signatures as of this writing.

BuzzFeed reports that Palmer’s practice is currently closed.

All of this rage about Cecil’s death—excluding the death threats—is certainly warranted given the upsetting nature of the killing and the high profile of “one of Africa’s most famous lions.” But as the Internet calms down from all this understandable rage, it’s important to take a step back and decide what #JusticeForCecil really looks like.

As the Internet mourns the loss of Cecil the Lion, the very existence of much of the Earth’s wildlife hangs in the balance.

In the grand scheme, Cecil is just one lion. Endangered animal deaths like this happen more regularly than we’d like to admit, yet rarely does it make headlines in the same way that Cecil did. Before anyone knew Walter J. Palmer’s name, five elephants were killed by poachers in Kenya. On Tuesday morning, park rangers discovered their carcasses in the Tsavo West National Park—“an adult female and four offspring,” the Washington Post reports—with their tusks severed. According to the report, elephants are at much greater risk of poaching than other animals in Africa, as ivory goes for $1000 per pound in Asia.

The Post report highlights the devastating effects of poaching on the African elephant population, noting that “[b]etween 2010 and 2012, poachers killed more than 100,000 African elephants.” Although lions aren’t hunted as frequently as elephants, they still face similarly frightening decreases in population. According to National Geographic, there are fewer than 30,000 lions alive today—a sharp decline from the nearly 200,000 that were around a century ago.

Both animals face extinction within this century. However, it’s not trophy hunters that are a threat to the lion population, and it’s not just lions and elephants that are threatened.

Vox reports on a Duke University study that found that the biggest threat to the lion population is “loss of habitat.” As populations grow, space for wildlife becomes scarce, and protecting these animals depends on how human populations handle this proximity to animal populations beyond lions. When it comes to responsibly managing the global environment, humans don’t exactly have the best track record.

It’s easy to write this off as a problem that only exists over there, but this decline is happening globally. In the past 40 years, the number of wild animals on Earth has decreased by half. A direct effect of human consumption, animals are vanishing as humans continue to “kill them for food in unsustainable numbers, while polluting or destroying their habitats,” according to a study conducted by the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London.

When it comes to responsibly managing the global environment, humans don’t exactly have the best track record.

“If half the animals died in London zoo next week, it would be front page news,” ZSL’s director of science, Ken Norris, told the Guardian. “But that is happening in the great outdoors. This damage is not inevitable but a consequence of the way we choose to live.” WWF calls this revelation a “call to arms” for the efficient production of food and energy, as well as the need for protections from deforestation and development on the rest of the planet.

The study analyzed 10,000 different animal populations and 3,000 species, and the data was included in the Living Planet Report, which categorizes the causes of the decline of mammals, fish, and birds; exploitation and habitat degradation are the biggest culprits. “These [animals] are the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems which sustain life on Earth,” the report states. “We ignore their decline at our peril.” The findings of the 2014 report are dire, and we are all complicit.

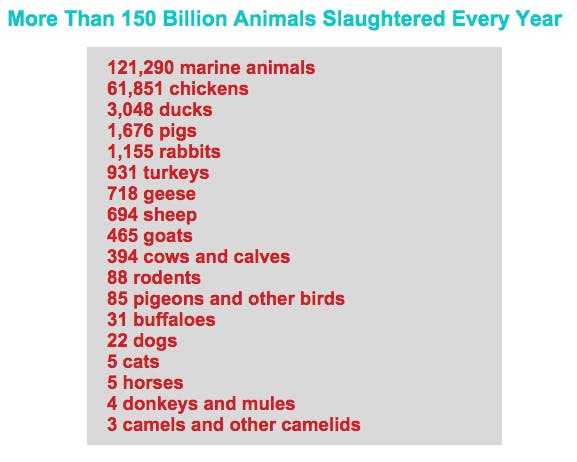

And yet, this exponential decline of animal populations—which has a huge effect on global ecosystems and our lives—fails to make headlines in the same way Cecil the Lion’s death did, reinforcing Norris’ point. This is despite the fact that, according to estimates, 150 billion animals are killed by humans each year.

Justice for Cecil certainly begins with his killer being held liable, but in order to truly exact justice, we all need to hold ourselves accountable for the animals that die at exponential levels each day. It’s time to make the necessary changes to reverse the trend: Support climate change candidates in upcoming elections, campaign for legislation to regulate emissions and corporate pollution, help clean up a river, and do anything you can to make an impact.

Without significant changes in the next 50 years, there may not be another Cecil the Lion to hashtag.

Feliks Garcia is a writer in Brooklyn. He holds an MA in Media Studies from the University of Texas at Austin, is Offsite Editor for The Offing, and previously edited CAP Magazine.

Screengrab via The National/YouTube