Chris Mastrianni couldn’t remember his Twitter password. He didn’t have much use for social media since he had wrestled in college, and even then, he barely participated. When A&E pitched a new police show, Live PD, that would feature the Richland County (South Carolina) Sheriff’s Office and a few of the deputies who worked there, including Mastrianni, he had a tiny Twitter presence of about 100 followers, and he had forgotten how to log onto the site.

Now, after zooming to the top of the TV ratings chart in its initial run, Live PD has begun its second season, and Mastrianni is one of the show’s biggest internet stars who was involved in the series’ most iconic moment.

When Mastrianni revved up his engine and began a police car chase on the night of July 8, he had no idea that his life was about to change. No longer was he Mastrianni, the police officer in Columbia, South Carolina. Hell, he wasn’t even Mastrianni, the guy who had been followed by cameras on Live PD and, before that, on the long-running Cops series, taking in whatever small amount of fame those appearances radiate.

Now he was Mastrianni, the social media superstar whose Twitter following bloomed from about 100 to, as of this writing, more than 53,000. The reason: the way Mastrianni performed during this dangerous incident with an erratic driver, a young child, a scary car accident, and an ensuing scuffle where the TV audience, but not Mastrianni, could see the suspect reach into his pocket for an unknown reason.

It was the most viral moment Live PD has yet produced, and it transformed Mastrianni into one of the show’s biggest stars.

The incident—and the fact as many as 2 million people were watching the show as season 1 neared its end—changed Mastrianni’s life.

“I’m not glad it happened, because the situation was so dangerous,” Mastrianni told the Daily Dot. “But I’m glad viewers are now able to see that this happens every day for officers. Now it’s shedding light on what actually happens.”

That was the point in starting the show. Yes, it’s an entertaining (and controversial) three-hour ride-along every week that’s basically a combination of Cops, America’s Most Wanted, and the NFL RedZone Channel. But for creator Dan Cesareo, the idea was to show police departments shedding light on how their officers do their jobs.

In the wake of the police killings of Michael Brown, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice, Cesareo’s plan was born from the idea that police departments are now using social media to engage their communities while actively patrolling and keeping the its citizens safe in a transparent way.

Cesareo had read an article about officers in the Los Angeles suburbs who were livetweeting during their shifts, and later, he discovered that deputies in Walton County, Florida, sometimes would use Periscope to livestream their job duties. Law enforcement in America is a hot topic of conversation, and Cesareo figured that if he could convince police departments to let his cameramen into their cars, they’d have an interesting show.

Cesareo and his company, Big Fish Entertainment, started developing Live PD in the fall of 2015—a show that would follow six departments across the country as their officers patrolled the night shift, using more than 30 cameras for a single episode— and it premiered in October 2016. Since then, about two dozen departments have been featured during the run of the show (a few have also declined to renew their contracts with A&E amid complaints and negative press).

It takes cues from Cops as cameramen record interactions between the police and the public (unlike Cops, though, most of Live PD is shown live with a short time delay). It takes inspiration from America’s Most Wanted as they actively ask for help to catch criminals from those watching on TV and following along on social media. And it takes the ingenuity from the NFL Redzone channel as host Dan Abrams and analyst Tom Morris Jr., bounce from city to city whenever an interesting pursuit or interaction begins.

One minute, it’ll show an extended police chase in Spokane, Washington. The next moment, it’ll be officers and their police dogs in Jeffersonville, Indiana, conducting a drug search on a car that smells like weed. A few seconds after that, you’ll see cops in Calvert County, Maryland, giving sobriety tests to potentially drunk drivers.

Mastrianni calls it “controlled chaos” inside the A&E studio, and the same could be said for what happens on the streets of America. Mastrianni knows that better than anybody, especially when, during his viral fight, the suspect—who was charged with resisting arrest, ill treatment of a child, and other traffic charges (his 2-year-old daughter’s arm also was broken during the scene)—reached into his pocket at the 1:48 mark of the video without Mastrianni’s knowledge.

The viewers could see it. But he couldn’t until he watched back the video later, a moment Mastrianni called “unnerving.” That’s a good description for the show, actually. It also can be highly entertaining. Not to mention scary and emotional. And, sometimes, funny.

More than anything, though, it’s interactive.

…

When Big Fish Entertainment and Cesareo began developing the idea of what Live PD would eventually become, there was so much to consider. How do you operate a three-hour show twice a week where there’s no set rundown, where you have 126 minutes to fill, and where directors need to make split-second decisions about which footage in which city to use? But he and his crew could figure out most of that before the series began and then make adjustments as they got more experience telling the stories every Friday and Saturday night.

What Cesareo didn’t envision was how quickly the show would become an internet favorite with what show analyst Tom Morris Jr. termed the “Live PD Nation.”

“When I joined the show in episode 11, the Twitter following was already growing,” Morris said. “It kept growing, and the interactions of the fans started to blow my mind. They were so obsessed with the show, and they were so supportive of what we’re doing… It’s an organic thing. We’re watching the Twitter feed and the live fan pages that are out there. We’re watching what’s trending during the show. We’re all kind of interacting back and forth. It’s pretty effortless and seamless. It’s become natural.”

What happened near the end of season 1 is a good example of how fans interact with the show online. This was when Jeffersonville K-9 Officer Alyssa Wright scuffled with and then took down two people at the same time during a domestic disturbance call.

Twitter reacted in real time.

For those of you who haven’t seen #OfficerAlyssaWright ‘s take down tonight. Here we go!!! #LivePD @AETV #2People2Dogs 👮♀️ pic.twitter.com/VmEXhGIqPW

— Lex_571 🇺🇸 (@Lex_491) August 6, 2017

#livepd…Way to go Officer Wight…you were awesome…..my favorite part was when you sent that dude flying….

— Beverly Rowe (@beverldrowe) August 6, 2017

https://twitter.com/mserin0114/status/894075807450222592

Officer Wright is everything every woman should aspire to be #LivePD pic.twitter.com/wE7mw7w7AZ

— Ren.🌻 (@kayerenna) August 6, 2017

https://twitter.com/married2livePD/status/894078261772263424

The look you have when you know you are a #badass 😆😆😆 #LivePD #AlyssaWright 👮♀️🚓 pic.twitter.com/poIkb0e6gf

— 🇺🇸NOT🚓THE🇺🇸POLICE🤔 (@BlameTheBadge) August 6, 2017

“You got big balls” yes you do Alyssa, yes you do. #beast #LivePD

— Lo❤Ko (@LaurenKoci) August 6, 2017

Damn #OfficerAlyssaWright with a 2-for-1 takedown!

— Pamela Nielsen (@Pamnielsen) August 6, 2017

As the perp so “eloquently” put it….#LivePD pic.twitter.com/NdT9F8Y5k8

To all the folks who think women shouldn’t be cops: She restrained 2 people alone and can probably kick your behind no prob. #LivePD

— Fruitvale Local (@fruitvalelocal) August 6, 2017

Not everybody was impressed, though.

https://twitter.com/evillynne17/status/894080992432062464

From all the talk on twitter I thought she was really wrestling w/ them but that was a weak shove & he fell #LivePD #iCouldntDoItThough lol pic.twitter.com/LpDxkeZ4gG

— 【L】【i】【s】【e】 (@ya_gurl_leecy) August 6, 2017

Since Wright patrols with a K-9 in her car, Twitter users wondered why she didn’t have her dog, Cairo, by her side when she made contact with the two people. As a result, Wright answered the question via Twitter.

#livepd @LivePdFans Update from Alyssa: pic.twitter.com/2crjhFgC6u

— JeffersonvilleLivePD (@JPD_LIVEPD) August 6, 2017

Said Cesareo: “You’re seeing this very unique conversation between departments and the public. It just didn’t exist before.”

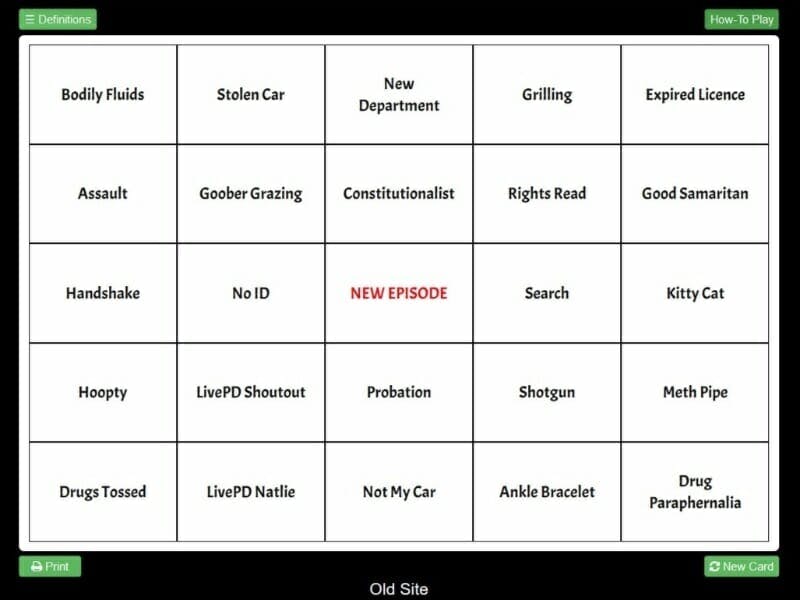

Social media users have another reason to follow along in real time. They’re trying to pursue their own sense of glory—by winning at Live PD Bingo. All you have to do is click on livepdbingo.com, and you’ll get a sample ballot like this.

Make your mark, and when you fill your board, brag about it on Twitter with the #LivePDBingo hashtag.

I think I won #LivePDBingo tonight! @RealityPDBingo @LivePdFans #LivePD #LivePdFans pic.twitter.com/80EBuieZN9

— 🐺 Kaj LoneWolf ♿ (@MaKyah) October 15, 2017

It’s not just fun and games, though. Those departments also rely on the public’s help to find criminal suspects. Not unlike America’s Most Wanted, Live PD engages the TV viewers and social media users in hopes of finding those wanted by the police. Live PD has said that tips from viewers have helped capture eight suspects. Meanwhile, the police departments monitor Twitter during and after the show in case viewers catch something their officers didn’t.

The best example occurred in season 1 when Richland County deputy Kevin Lawrence was involved in a car chase as a suspect threw something out the Lexus’ window as the police were pursuing. Lawrence didn’t see it at the time, but Twitter users—and their ability to rewind, fast forward, and slow down the footage—caught it.

You missed something flying out the left driver window #ColumbiaSC #livePD @OfficalLivePD pic.twitter.com/PscwefqWcH

— Chris Breezy❥ (@cwissyk) March 18, 2017

Later, after he was informed of Twitter’s investigation, Lawrence, who later said it’s “really helpful having extra eyes and ears,” returned to the scene and found a baggie of drugs. The idea that viewers can affect the show and, in a small way, help put suspects behind bars was not something Cesareo could have predicted.

“Our communities have evolved and the relationship between the public at large and law enforcement have gotten strained at times, and we’ve moved away from this sense of community,” Cesareo said. “The show encourages dialogue. The dialogue is happening on the air. There’s been a ton of law enforcement programming that’s been produced prior to Live PD. … But we could never have imagined the way the audience responded to this. It’s gratifying to see the variety of opinions and the dialogue the show encourages.”

The social interactions provide Live PD real-time feedback, which the show can use to determine if an incident needs more explanation or if something specific is resonating with viewers. That kind of technological latitude allows Live PD to make adjustments from week to week to better tell the story.

The show also encourages viewers to send in Twitter questions to its frequent special guests—which normally includes Tulsa Sgt. Sean “Sticks” Larkin but also has featured Mastrianni and Wright after their viral incidents—so they can answer in real time on the air. And when a Twitter user has a question about the circumstances of an arrest (for instance, in season 1, when a Calvert County officer was investigating a fight at a movie theater, a follower asked what film had been playing), the crew tries to find the answer (it was Atomic Blonde).

“The amazing thing about the social media response is the level of investment the viewer has in the show,” Cesareo said. “They’ve really embraced the concept and the content. They’re engaging with it in ways that we never in a million years could have dreamed of. For us, we really want this show to be straight down the middle. We don’t have an agenda. Our job is to document these interactions and put them out on the show and let the viewers judge. That’s what you see happening.”

Not everybody, though, agrees the show is accomplishing this mission.

…

The show has been a hit for A&E. A press release from the network in July said Live PD had grown 152 percent in total viewers and had become cable’s No. 1 show for people in the 18 to 49 age range (the weekend after the Mastrianni incident, 2.1 million people watched, and between 1.6-1.8 million per show have tuned in to season 2). As a result, A&E in July ordered 100 more episodes.

But the show has its critics.

The Outline wrote a story with the headline, “A live version of ‘Cops’ is the most disturbing show on TV,” and some of the footage shown has been invasive and distressing.

One example occurred early in the first season when Bridgeport (Connecticut) officer Christopher Robinson wept on camera after a 1-year-old boy involved in a call to which he was responding died on his way to the hospital.

The Bridgeport Police Department eventually cut ties with the show, telling the Connecticut Post, “… Despite its merits, the program was giving Bridgeport an inaccurate national reputation; inflating the prevalence of crime in the Park City in a way that can deter potential investors and people from living or doing business here. … A community should be defined and judged by the best it has to offer, and not by its worst moments.” The Tulsa Police Department, despite allowing Larkin to continue participating on set, also declined to renew its contract with Live PD.

It’s also not uncommon for suspects who are being questioned or put in handcuffs by police to ask (or demand) that A&E’s cameras not shoot them. Those remarks are usually met with a “Don’t worry about them, worry about me,” comment from the officers (it’s also interesting that during the pre-taped segments that show past incidents, the suspect’s faces are often blurred out, something that doesn’t occur during live scenes). Critics wonder if there is some expectation of privacy for those who are involved in a police matter, though the show makes sure a suspect’s personal information—last names, birth dates, and social security numbers—are edited out of the broadcast.

Camera operators also don’t enter a suspect’s home, and they seem to make an effort not to film children.

Cesareo, who won’t disclose how long the live delay is, said the show follows the same ethical guidelines and standards as every news program in America, pointing to the combined 100,000 hours of live primetime experience in the studio.

There’s also the thought that the show skews heavily pro-law enforcement (Abrams and his analysts are rarely —if ever—negative in their analysis of how an officer handled an incident), which can feel a little out of touch to viewers who believe police are abusing their often-unchecked power. But in Morris’ mind, it’s not about choosing a side. It’s about transparency and how education can be born as a result.

“I love the fact this show [exists] in this time of discourse; here the public gets to see six jurisdictions on any given night, showing officers doing what they do in real time,” Morris said. “It’s the third eye on the whole process. When you see five white officers working to save the life of a young black men who’s just been shot by another black man, you realize this whole [negative] discourse with police work, it’s not really that way.”

Said Mastrianni: “What we do every day, we deal with people and see them at their worst times. That’s stressful for anybody. We know we’re in a situation where not everybody is going to like what we do. Our job is to enforce the laws. Has it been controversial? Yes. But this show has shown our side of the story. Its paints a picture of what we deal with. We need to make split-second decisions, and then we figure out what our next mode of operation is going to be, whether it’s putting them in jail, writing a ticket, or letting them go free.”

…

In the days after his encounter with the runaway driver and his 2-year-old, Mastrianni had a difficult time sleeping. Though he said he felt he did everything he could, he still thought about the what-ifs. What if an incoming police car had accidently run over the child while coming to Mastrianni’s aid? What if help never came? What if the suspect had pulled out a knife or a gun from his pocket?

He could watch back the episode and study his actions, but the questions still lingered.

Ultimately, though, he looks at the show and his experience as a positive.

During the course of season 1, Mastrianni’s boss joked with him that he was going to get all kinds of new recognition and that Mastrianni wasn’t going to be ready for it. Now, he’s recognized at the grocery store. He’s throwing out the first pitch at the local minor league baseball game. He’s got a robust Twitter following.

He’s not an actor. He’s not an entertainer. Mastrianni and his officers don’t have the training to sing and dance for the cameras.

“I just signed up to protect people and do my job,” Mastrianni.

Lucky for A&E, viewers apparently want to keep riding along.