It would not be an overstatement to say that Celebgate consumed the Internet on Monday. The leak of dozens of hacked photos from female celebrities, such as Jennifer Lawrence, Kristin Dunst, Kate Upton, Rhianna, and Kim Kardashian, initially came through the anarchic message board 4chan, but quick spread across the rest of the Internet.

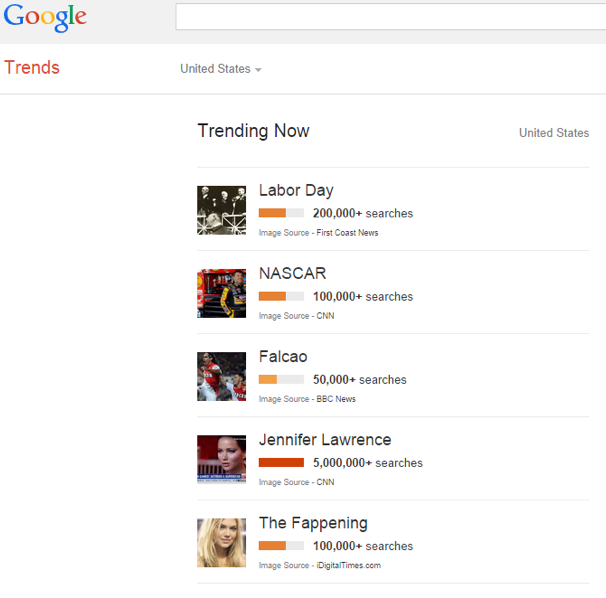

How much did people want to see the pictures? Well, here’s a screenshot of the Monday’s top trending Google searches:

In the United States alone, there were over 5 million people searching for Oscar-winner Jennifer Lawrence. Sure, some of those people may have been looking for info about the upcoming Hunger Games sequel, but it’s a safe bet that a good chunk of them wanted naked pictures. The search phrase right below the actress’s name, ?The Fappening,” is the label given to the community on Reddit that quickly became the central hub for the leaked photos.

In fact, r/thefappening managed to go from not existing on Sunday to accumulating over 119,000 subscribers on Tuesday morning. To say that it was the fastest-growing subreddit of the past 30 days wouldn’t do it justice. The second fastest-growing new subreddit over that period only racked up around 5,000 subscribers—and that one had been around for weeks rather than days. Over a 24-hour period, the subreddit was racking up 72 new followers every minute.

R/thefappening was attracting so much traffic on Monday, over 9 million unique pageviews in all, that Reddit spent most of the day experiencing intermittent outages. Anyone attempting to log onto Reddit was basically out of luck.

While the Celebgate photos attracted a massive amount of interest, a chorus of commentators loudly insisted that the theft of the images was a massive violation, and either viewing or sharing them online was tantamount to sexual harassment or assault.

In an op-ed that captured the overall sentiment of many who reacted with instant revulsion to the leaks, a writer for the Australian website Daily Life charged:

If you deliberately seek out any of these images, you are directly participating in the violation not just of numerous women’s privacy but also of their bodies. These images—which I have not seen and which I will not look for—are intimate, private moments belonging only to the people who appear in them and who they have invited to see them. To have those moments stolen and broadcast to the world is an egregious act of psychic violence which constitutes a form of assault.

And yet, millions of people looked. It was trove of naked pictures of famous people suddenly released on the Internet—the desire to look at them is the most natural thing in the world.

At least, until you really start to think about it. Then, the whole thing goes a little sideways.

At its most basic, Celebgate is just a bunch of pictures of naked people onto the Internet. The Internet is already packed to the brim with pictures of naked people. Sure, the leak was full of pictures of attractive naked people, but the Internet has thousands upon thousands of websites exclusively devoted to people who look so good naked that they’re able to do so professionally.

It could be argued that what made Celebgate so interesting was the violation. These are candid shots. Unlike the sea of professional pornography, they weren’t created for mass consumption. They’re intimate and therefore, less cynical. However, as the epidemic of revenge porn as made abundantly clear, this isn’t particularly novel either.

So, what accounts for 5 million people in the U.S. alone desperately scouring the Internet to find these photos? Or the 9 million people around the world that logged into r/thefappening?

One of the best explanations comes from an unlikely source: an essay written nearly 35 years ago, before anyone but even the most forward-thinking computer scientists had even heard of networked computer, about the pernicious influence of an entirety different medium.

In the fall of 1980, the New Yorker dedicated an entire issue to a single essay, ?Within the Context of No Context,” by writer George Trow. Trow, who cut his teeth satirizing pop culture as an early writer for National Lampoon, penned a dizzying, impressionistic analysis of how television simultaneously isolated individuals and infantilized American culture. Trow’s arguments may be couched in a WASP-y reactionary elitism, but his insights into how people interact with the culture at large—and celebrity in particular—have remained just as relevant and insightful over the ensuing three decades since its publication.

Trow explained that the best way to think of a person’s life is to view it as a pair of grids mapping their interactions with others. The first grid is intimate, comprised of friends and family members. The second grid is national, connecting every single person in the country through a shared culture. As people stopped going out into their communities and participating in things like bowling leagues and social organizations, opting instead to sit at home and watch TV, their intimate grids started to shrink as their dependence on the national grid grew accordingly. ?It was sometimes lonely in the grid of one, alone,” Trow wrote. ?People reached out toward their home, which was in television. They looked for help.”

Famous people, on the other hand, have a much different experience. ?Celebrities have an intimate life and a life in the grid of two hundred million,” Trow explained. ?For them, there is no distance between the two grids in American life. Of all Americans, only they are complete.”

However, that ?completeness,” as Trow labels it, comes at a cost—issues that, for normal people, would only be discussed across their personal grids are nationalized because a celebrity’s grid is also national. If you or I were to get wildly drunk at a party, doing something that could be charitably labeled ?moronic,” information about it would only spread across our small, intimate grids—unless, of course, a video of what happened ened up on YouTube.

For celebrities, from whom both grids are effectively merged, information about the party could spread to everyone connected to the larger grid, which is basically everyone. This spread, at least in 1980, was facilitated by gossip magazines like People, for which Trow seemingly has endless scorn:

What is the function of…People? It is to unite, for a moment, the two remaining grids in American life—the intimate grid and the grid of two hundred million. This is discussing the intimate life of celebrities who have their home in the grid of two hundred million and by raising up to national attention certain experiences of Americans as they live, lonely, in the grid of intimacy.

Trow didn’t view the gossip of his time as particularity interesting or authentic. It was pre-packaged to best appeal to advertisers selling products that were, quite often, the celebrities themselves.

The Celebgate leaks are essentially celebrity gossip taken to its logical extreme. The nude photos are the manifestation of the affected celebrities’ intimate grids merging with the national grid of pop culture. Only, this time, the images were released without an intermediary reformatting and repositioning them in such a way that they’d sell the most ads for shoes or the upcoming summer blockbuster.

On one hand, looking at the leaked photos is akin to someone coming across a sexy photo of a coworker on an Internet dating site. The natural inclination is to look, but lusting over a coworker can come with an pang of guilt that, likely for most people viewing them, didn’t occur with the Celebgate photos. That’s because the context in which most people relate to these celebrities is essentially performative; we’re used to looking at them on camera, effectively as product. This familiarity obscures the fact that looking is still looking and people are still people, no matter how many Oscars they have on their mantlepiece.

Asking people not to look is futile. The millions of people who sought out the photos on Monday, and will likely continue to seek them out, are evidence of that futility. Will looking make anyone less isolated or give anyone more insight into anything? Or is the ultimate result just that a bunch of young women had their privacy violated by millions of people who didn’t even give a moment’s serious consideration to what they were doing?

Trow died in 2006, so he’s not around to proffer his opinion. But, it’s probably safe to say that his answer wouldn’t be an optimistic one.

Photo by Michell Zappa (CC BY SA 2.0) | Remix by Jason Reed