This is a story about race in the art world.

An art collective withdraws its work from one of the most prestigious exhibitions in the country, citing another participant in the show as racist. This other artist is a white male Ivy League professor who creates art under the fictional identity of a black female. An art blogger writes a satirical Internet post faking this artist’s identity.

Some misunderstand the post to be real, and believe the artist to be, like his creation, a fictional persona. It’s a Gordian knot of constructed identities and complicated racial signifiers, as compelling as it is confusing.

It starts in November 2013, when the list of participants in the Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial 2014 was released, sparking immediate concern within the art community, as only a handful of artists of color were represented.

As Brooklyn-based art blog Hyperallergic noted at the time, only nine of the 103 artists in the 2014 Biennial weren’t white. This somewhat contradicted the Whitney’s claim that the 2014 Biennial was “one of the broadest and most diverse takes on art in the United States that the Whitney has offered in many years.” And to further complicate the discrepancy, one of these nine, Donelle Woolford, was actually a fictional persona created by a white male Princeton art professor, Joe Scanlan.

Scanlan. Photo via Princeton.edu

The Donelle Woolford character was conceived by Scanlan in 2005, as part of the artist’s process in creating a series of sculptures and collages. Over time, the character grew in scope, and eventually Scanlan hired actors to play her, appearing at galleries and participating in performance art pieces.

Said Scanlan in an interview with BOMB Magazine:

Donelle Woolford began … when I first appropriated her name from a professional football player I admired. After the first collages happened in my studio, I liked them but they seemed like they would be more interesting if someone else made them, someone who could better exploit their historical and cultural references.

Scanlan has experienced both acclaim and outrage from the art community about the problematic implications of his work as Donelle Woolford. Some have called it “minstrelsy,” even “conceptual rape.” And yet the Whitney Biennial’s co-curator Michelle Grabner told the New York Observer, “Joe was the very first artist I asked to visit when I started on my studio-visit process for the [Whitney Biennial].”

In Scanlan’s recent interview with the Los Angeles Times, the artist indicated that the complicated racial undertones in his Donelle Woolford project was always part of the point in creating her.

In the beginning, I saw it more as a right and obligation that I had as an artist to be willing to engage with all parts of the world, just as any novelist or screenwriter would. But I have always been aware of how fraught the power relation of myself to Donelle Woolford is. I am interested in that trouble and in seeing if it can be destabilized by taking it too far, on the one hand, but also by seeing if it can be dismantled, piece by piece.

One of the black female actors portraying Woolford, Jennifer Kidwell, has loudly defended Scanlan and their project. Said Kidwell to the Times:

He explained the project and you know what I said to him? I said, ‘No, I don’t want to be involved in your post-colonial [trash].’ But then we talked further and discussed how important identity is to the way we receive art. It then became a personal challenge to me, investigating that question of why that is so important and how it changes an audience’s relationship to an artwork.

However, one art collective showing at the Biennial did not see it that way. HowDoYouSayYamInAfrican?, otherwise known as “The Yams Collective,” is a group of 38 artists of color who had been invited to participate in the Whitney Biennial 2014 to show their film Good Stock on the Dimension Floor: An Opera. And on May 14, the Yams withdrew from the Biennial over Scanlan’s participation and the Whitney’s history of “white supremacy.”

Upon their withdrawal, Yams member Maureen Catabagan stated:

We felt that the representation of an established academic white man posing as a privileged African-American woman is problematic, even if he tries to hide it in an avatar’s mystique. It kind of negates our presence there, our collaborative identity as representing the African diaspora.

Other members of Yams Collective said their reasoning for withdrawal was more nuanced. Collective member Christa Bell said that Scanlan was not even their main motivation for withdrawal: “I want to clarify. This is not about Joe Scanlan. We are not protesting Joe Scanlan, or [Biennial co-curator] Michelle Grabner. We are protesting institutional white supremacy and how it plays out.”

Another Yams member Sienna Shields said that even the collective’s initial participation was a protest of racism within the Biennial. Said Shields:

I was pissed off about the history of the Whitney and its lack of any kind of initiative in changing its white supremacist attitudes. So we formalized our collective and group to not only do this project, the movie, but to use this opportunity to infiltrate an institution and to experience firsthand what happens in the art world in terms of white supremacy, to expose how the doors are closed for the majority.

In her interview of Joe Scanlan, L.A. Times writer Caroline A. Miranda refers to his performance art piece Dick’s Last Stand—in which actor Jennifer Kidwell plays Scanlan’s creation Donelle Woolford, who in turn performs in drag as Richard Pryor—as a “conceptual turducken.” Nice turn of phrase.

What happened next could be called a conceptual turducken, swallowed by a catfish.

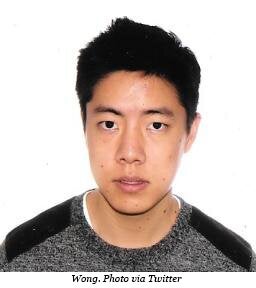

Three days ago, a blogger and art curator named Ryan Wong published a piece in Hyperallergic titled “I Am Joe Scanlan,” claiming that Scanlan himself was a persona Wong had created to draw attention to racism in the art world.

Joe Scanlan is the artist who supposedly teaches at Yale and Princeton Universities, and whose Donelle Woolford project was one of the major framing works of this year’s Whitney Biennial. As intended, the project has set off a healthy and robust debate about the realities of race, class, and gender privilege within the art world, culminating in the decision of the Yams Collective to withdraw from the Biennial.

Now that the Whitney Biennial is over and the critical debate around it has subsided, I feel it’s time to put this project to rest: I created Joe Scanlan.

Wong’s piece was satire, or “meta-parody”—a send-up of Scanlan’s efforts to appropriate the identity of a black woman. But in yet another layer, many people who only knew of Scanlan via the Whitney Biennial controversy took Wong’s article at face value.

I contacted Joe Scanlan about Wong’s piece and had a fairly lively email interaction with him.

Self-Portrait (Pay Dirt), Joe Scanlan. Photo via Galerie Martin Janda

…

Have you seen the Ryan Wong post, and would you care to comment on it, or anything else beyond your released statement?

Scanlan: I did see the Ryan Wong post, which was funny, but I thought it could have been funnier. Too bad his desire to score points overwhelmed his desire to be entertaining, and that’s when it stopped being so. Anyway, it was a funny idea and certainly worth doing. One good turn deserves another, and in that sense it validated Donelle Woolford at my expense. What do I care? Either way I can’t lose.

I’m not interested in commenting beyond that. But a better question might be, why have me respond at all? Wouldn’t that prematurely close the loop? Better would be for you to find someone else to write an “I am Ryan Wong” piece, someone interested in impersonating an ambitious young artist who knows a good ambulance to chase when he sees it. Then someone else can write the “I am so and so” piece after that, and so forth.

Do you agree? If so great, I could put you in touch with some good writers who could keep the chain alive.

You know that’s an interesting idea, but I’m not sure I do agree. Your work and Ryan’s piece are very different. His post isn’t merely an impersonation but a satire of your work, so would the continuation of the loop be a satire of a satire? I’m not sure that would be as effective. Or not in the same way.

I think it’s possible that the totality of the loop itself could be interesting (if one could think of it ever being “total” if it just goes on indefinitely) but not the individual links. A never-ending chain of impersonation would be quite a spectacle, but certainly not by virtue of each individual part. The power of his satire would certainly be diminished by participating in something like that, don’t you think?

Precisely. The point of satire is to undermine. Not sure what reason there would be to protect the “power” of one satire over another. That would seem contrary to the idea of satire.

Well, the reason to protect the power of one satire over another would be to protect the point of that satire, its subject. If one thinks a given bit of satire makes a valid point, it would be worth protecting. The “power” I meant concerning Ryan’s piece was its ability to effectively comment on your work. Formally, satire has to be about something. If it becomes a recursive loop of satire after satire, as you suggest, I’m not sure it would be “about” something in the same way. It would become a different sort of rhetoric, not satirical.

This sort of thing certainly wouldn’t preserve Ryan’s original point, which some think is worth making, though I would understand if you didn’t.

But I mean that’s all sort of academic. Do you think the point of Ryan’s post has merit, that there are problematic power structures at bottom of the Donelle Woolford project?

Well, duh. Is that really something you, or he, think is not obvious?

The flaw (and tacit racism, frankly) in Ryan’s satire is that he assumes I have an unwavering power over Jenn Kidwell, which he mimics in his power over me. If you read Carolina Miranda’s L.A. Times piece, or had the pleasure of being present at one of our rehearsals, you would learn otherwise.

Ultimately, from our (Jenn’s and Abigail’s and my) point of view, this is really a question of people’s very real inability to accept that a white man and two black women can acknowledge their unequal power relations and still decide to happily work together, because something might be accomplished that is greater than that inequity. I think that greater thing has already been accomplished. Because of the knowledge we have of ourselves and our relationship to each other, we really aren’t much troubled by other people’s perceptions of us, except when they blatantly choose to ignore this fact.

I think our civility throughout this controversy, when we’ve cared to address it at all, proves that. We’re really at peace with ourselves; it’s mostly everyone else who’s all worked up.

So I guess I’m not really interested in responding to Ryan’s satire, I think it works best as an end in itself.

…

I also also exchanged emails with Ryan Wong:

What led you to write the Joe Scanlan parody?

Wong: Eunsong, one of the authors of the powerful New Inquiry piece criticizing the Whitney Biennial, joked to me that it would be amazing if someone came out and admitted they were Joe Scanlan, that this had been an elaborate ruse. We can’t change reality, but we can find ways to take ownership of and disrupt alarming projects like Scanlan’s.

Wong: Eunsong, one of the authors of the powerful New Inquiry piece criticizing the Whitney Biennial, joked to me that it would be amazing if someone came out and admitted they were Joe Scanlan, that this had been an elaborate ruse. We can’t change reality, but we can find ways to take ownership of and disrupt alarming projects like Scanlan’s.

I wanted to use humor to understand this project. When talking race, gender, and class politics, power structures tell you to internalize rather than externalize: you have the problem, not us. The Scanlan essay is an extreme example of externalizing: creating a fictional narrative in order to deflate the power and willful ignorance Scanlan flaunted.

Hyperallergic and I did not set out to trick anyone into thinking this was a real project. Because the piece went small-scale viral, it reached a lot of people who weren’t actually following the Biennial story, who didn’t know Scanlan was a real person.

How do you respond to Scanlan’s defense of himself?

I’m wary of his suggestion that he has the “right,” as an artist, to create projects without thorough consideration. Art is a realm of exploration and experimentation, but it still exists within social and historical contexts.

Scanlan’s project exists within some very fraught histories in America: blackface, cultural appropriation, and the subjugation of black women by white men in power. But in the interviews I’ve seen, Scanlan seems willfully opposed to engaging with or even learning those histories. Instead, he uses conceptualism as a shield: he doesn’t have to discuss subjugation if he discusses intentionality, he doesn’t have to discuss race if he emphasizes destabilization.

What about the defense of Scanlan by the actors who play Donelle Woolford, particularly Jenn Kidwell?

One of the ironies of this debacle is that Kidwell actually articulates the power dynamics that Scanlan, in his interviews, fumbles. She gave a very compelling interview in the LA Times this week. It sounds like the project has evolved, and that Kidwell and Ramsay have more ownership of the project now than at the beginning.

Maybe Scanlan will relinquish control of Woolford to Kidwell. Maybe he’ll give her his teaching position: that would be the ideal next step in the project.

I’ve contacted Joe Scanlan about your parody, and he read it and said it was funny, though he also said it was more about “scoring points” than being funny.

This piece was not just about Scanlan himself, but the rampant ignorance in the art world regarding institutionalized race and gender biases. The piece asks all of us to examine our own patches of ignorance: do we deflect, as Scanlan does, or try to grow through them?

I’m glad he was able to find some humor in it: I certainly had fun writing it.

Scanlan also suggested finding a writer to do an “I Am Ryan Wong” post to “keep the chain going” as he put it. How do you respond to that?

He’s more than welcome to create an “I Am Ryan Wong” essay, of course. But, for the sake of his PR, I wouldn’t recommend it: internationally-exhibited artist and director of Princeton’s art department goes after young, part-time art writer? Plus, this could end up in an infinity loop, a la Macaulay Culkin wearing a T-shirt of Ryan Gosling wearing a T-shirt of Culkin.

Maybe Scanlan could make me a T-shirt, instead.

…

We’ll update this story with any developments about whether Joe Scanlan creates a T-shirt for Ryan Wong.

Photo via shinealight/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)